Alcibiades

Alcibiades, son of Cleinias, from the deme of Scambonidae (/ˌælsɨˈbaɪ.ədiːz/; Greek: Ἀλκιβιάδης Κλεινίου Σκαμβωνίδης, transliterated Alkibiádēs Kleiníou Skambōnidēs; c. 450 – 404 BC) historically was a Greek statesman and general. However, he has been best known posthumously as a disciple and especially the beloved boy (eromenos) of Socrates. This is clearly seen in Plutarch's life of Alcibiades [1], and in Plato's better-known Symposium. He has been, in post-Renaissance times, a coded symbol of pederasty. [2]

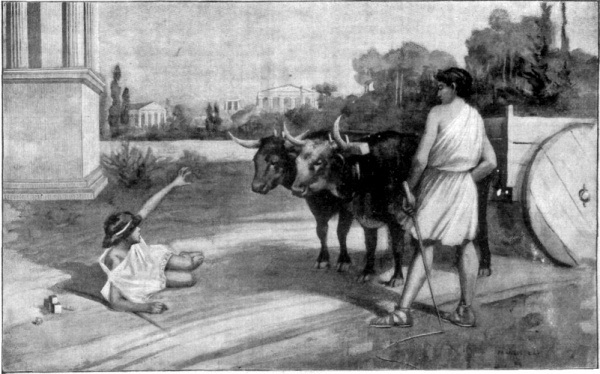

Even as a young boy, he was very strong-willed. And perhaps as he had no father and mother to restrain his noble boyish inclinations, he was sometimes led by his own tenacity and courage into great danger. We are told that once, when he saw a wagon coming down the street where he and his playmates were playing knucklebones (jacks), he called to the man to stop. The man, who cared nothing for their game, drove on, and the other children quickly sprang aside so as not to be run over. Alcibiades, however, flung himself down across the road, in front of his playthings, and dared the driver to come on. The man was so amused by the little fellow’s pluck, that he actually turned around and drove through another street.[3] [4] [5]

The historic Alcibiades was (at least):

- — an orphan, always looking for love;

- — a really beautiful, clever and charming boy;

- — a “headstrong” child—able to lie down in front of a moving wagon to force the driver to stop it;

- — a young adolescent who left his house to go and openly live with his lover (erastes);

- — Socrates's pupil and young friend;

- — later, an important character of Plato's Symposium and other dialogs;

A boy and his dog

One of the attributes of Alcibiades is that he is often shown in paintings with his dog and it is frequently a good indicator that it is indeed Alcibiades who is being depicted.

Plutarch explained why Alcibiades was famous for his dog. And why from this time, the animal has been associated with him:

| “ | Possessing a dog of wonderful size and beauty, which had cost him seventy minas, he had its tail cut off, and a beautiful tail it was, too. His comrades chid him for this, and declared that everybody was furious about the dog and abusive of its owner. But Alcibiades burst out laughing and said: "That's just what I want; I want Athens to talk about this, that it may say nothing worse about me." [6] | ” |

Love and lovers

| “ | Among the calumnies which Antiphon10 heaps upon him it is recorded that, when he was a boy, he ran away from home to Democrates, one of his lovers, and that Ariphron was all for having him proclaimed by town crier as a castaway. 193But Pericles would not suffer it. "If he is dead," said he, "we shall know it only a day the sooner for the proclamation; whereas, if he is still alive, he will, in consequence of it, be as good as dead for the rest of his life." Antiphon says also that with a blow of his stick he slew one of his attendants in the palaestra of Sibyrtius. But these things are perhaps unworthy of belief, coming as they do from one who admits that he hated Alcibiades, and abused him accordingly.

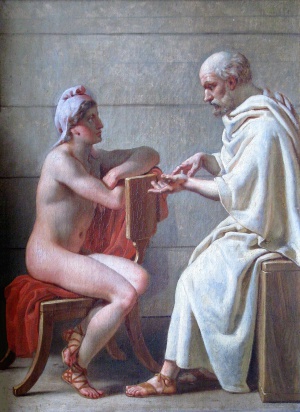

4 1 It was not long before many men of high birth clustered about him and paid him their attentions. Most of them were plainly smitten with his brilliant youthful beauty and fondly courted him. But it was the love which Socrates had for him that p11bore strong testimony to the boy's native excellence and good parts. These Socrates saw radiantly manifest in his outward person, and, fearful of the influence upon him of wealth and rank and the throng of citizens, foreigners and allies who sought to preëmpt his affections by flattery and favour, he was fain to protect him, and not suffer such a fair flowering plant to cast its native fruit to perdition. 2 For there is no man whom Fortune so envelops and compasses about with the so‑called good things of life that he cannot be reached by the bold and caustic reasonings of philosophy, and pierced to the heart. And so it was that Alcibiades, although he was pampered from the very first, and was prevented by the companions who sought only to please him from giving ear to one who would instruct and train him, nevertheless, through the goodness of his parts, at last saw all that was in Socrates, and clave to him, putting away his rich and famous lovers. 3 And speedily, from choosing such an associate, and giving ear to the words of a lover who was in the chase for no unmanly pleasures, and begged no kisses and embraces, but sought to expose the weakness of his soul and rebuke his vain and foolish pride,

"He crouched, though warrior bird, like slave, with drooping wings."11 And he came to think that the work of Socrates was really a kind of provision of the gods for the care and salvation of youth. 4 Thus, by despising himself, admiring his friend, loving that friend's kindly solicitude and revering his excellence, he p13insensibly acquired an "image of love," as Plato says,12 "to match love," and all were amazed to see him eating, exercising, and tenting with Socrates,13 while he was harsh and stubborn with the rest of his lovers. Some of these he actually treated with the greatest insolence, as, for example, Anytus, the son of Anthemion. 5 This man was a lover of his, who, entertaining some friends, asked Alcibiades also to the dinner. Alcibiades declined the invitation, but after having drunk deep at home with some friends, went in revel rout to the house of Anytus, took his stand at the door of the men's chamber, and, observing the tables full of gold and silver beakers, ordered his slaves to take half of them and carry them home for him. He did not deign to go in, but played this prank and was off. The guests were naturally indignant, and declared that Alcibiades had treated Anytus with gross and overweening insolence. "Not so," said Anytus, "but with moderation and kindness; he might have taken all there were: he has left us half." 5 1 He treated the rest of his lovers also after this fashion. There was one man, however, a resident alien, as they say, and not possessed of much, who sold all that he had, and brought the hundred staters which he got for it to Alcibiades, begging him to accept them. Alcibiades burst out laughing with delight at this, and invited the man to dinner. After feasting him and showing him every kindness, he gave him back his gold, and charged him on the morrow to compete with the farmers of the public revenues and outbid them all. p152 The man protested, because the purchase demanded capital of many talents; but Alcibiades threatened to have him scourged if he did not do it, 194because he cherished some private grudge against the ordinary contractors. In the morning, accordingly, the alien went into the market place and increased the usual bid for the public lands by a talent. The contractors clustered angrily above him and bade him name his surety, supposing that he could find none. The man was confounded and began to draw back, when Alcibiades, standing afar off, cried to the magistrates: "Put my name down; he is a friend of mine; I will be his surety." 3 When the contractors heard this, they were at their wits' end, for they were in the habit of paying what they owed on a first purchase with the profits of a second, and saw no way out of their difficulty. Accordingly, they besought the man to withdraw his bid, and offered him money so to do; but Alcibiades would not suffer him to take less than a talent. On their offering the man the talent, he bade him take it and withdraw. To this lover he was of service in such a way. 6 1 But the love of Socrates, though it had many powerful rivals, somehow mastered Alcibiades. For he was of good natural parts, and the words of his teacher took hold of him and wrung his heart and brought tears to his eyes. But sometimes he would surrender himself to the flatterers who tempted him with many pleasures, and slip away from Socrates, and suffer himself to be actually hunted down by him like a runaway slave. And yet he feared and reverenced Socrates alone, and despised the rest of his lovers. 2 It was Cleanthes who said that any one beloved of p17him must be "downed," as wrestlers say, by the ears alone, though offering to rival lovers many other "holds" which he himself would scorn to take, — meaning the various lusts of the body. And Alcibiades was certainly prone to be led away into pleasure. That "lawless self-indulgence" of his, of which Thucydides speaks,14 leads one to suspect this. 3 However, it was rather his love of distinction and love of fame to which his corrupters appealed, and thereby plunged him all too soon into ways of presumptuous scheming, persuading him that he had only to enter public life, and he would straightway cast into total eclipse the ordinary generals and public leaders, and not only that, he would even surpass Pericles in power and reputation among the Hellenes. 4 Accordingly, just as iron, which has been softened in the fire, is hardened again by cold water, and has its particles compacted together, so Alcibiades, whenever Socrates found him filled with vanity and wantonness, was reduced to shape by the Master's discourse, and rendered humble and cautious. He learned how great were his deficiencies and how incomplete his excellence. |

” |

Alcibiades the Schoolboy (Book)

Alcibiades the Schoolboy (L'Alcibiades, fanciullo a scola) by Antonio Rocco writen in the 17th century is a fictional dialogue in which Socrates portrays the excellence of sexual love between master and (male) disciple. Wikipedia says: "It is a tour de force of pederastic fantasy and one of the frankest and most explicit texts on the subject to have been written before the twentieth century. It has been called "the first homosexual novel". [7]

Review

First published in 1651 and meant at one level as a lively carnival booklet, this is, both at heart and on the surface, a well-reasoned polemic in favour of pederasty. The eponymous Athenian boy is presumably intended to be the famous Athenian general well-known for the amorous attentions he excited in his boyhood, but the book is a philosophical dialogue rather than a story about real people: Alcibiades's schoolmaster Philotimes is dying to consummate his love for his pupil and has to overcome with reason the full array of early modern arguments against sodomy raised by the initially reluctant boy, until the latter is finally eager to accept him.

There was a profound contradiction over pederasty in early modern Italy. On one hand, the authorities followed the church in denouncing and fiercely persecuting all sodomy. On the other hand, recent research such as Rocke's statistical study of Florentine court records in his Forbidden Friendships has proven the reports of contemporary writers that most men were involved with boys, and reinforced their implication that attraction to both women and boys was taken for granted (whether or not acted on).

Rocco was the most important of a tiny number of writers who dared counter the various arguments of God, law and nature which were supposed to justify this persecution. Those of God and the law are shown to be irrational inventions and nature is shown to favour the love of men and boys and its consummation. Rocco, or rather Philotimes, then proceeds to show how both these things are superior to the alternatives.

Lest it be supposed to be a sombre treatise, the fun should be explained too. Mostly, I think it comes from the sheer joie de vivre underlying the dialogue. There is plenty of satire ranging from the unphilosophical over-excitement of the supposed philosopher to the outrageous excess of some of his arguments. Also, the most serious arguments are so peppered with luscious descriptions of the boy's physical charms and frank sexual description as to be highly erotic. In this it offers a valuable lesson to modern writers on sexual matters whose dour vocabulary tends to be at odds with the joy which should be at the heart of their subject.

Considering all the old arguments against homosexuality have largely been abandoned in modern Europe, it is ironic that the only beneficiaries have been men loving men, described by Philotimes as "mere beasts" for their goatish tastes. Rocco's own book remains nearly as forbidden as ever, this the only English translation published having become virtually unobtainable within a few years and the form of love it upholds newly persecuted with an intensity the mediaeval inquisition could only have dreamed of managing. Today a new Rocco is badly needed, for despite doing his best to answer all, Philotimes was unable to anticipate a day when the adolescent consent to sex he fought so hard and well to obtain would be held in contempt. Nor could he foresee the perversity of an age which would see the sexual abuse of boys, which he fiercely denounced himself, as a justification for terrorising men and boys genuinely in love.

An excellent "Afterword" shedding light on the book by D. H. Mader overstates an important point: he claims it is early evidence of the modern homosexual identity explained by Foucault as having emerged in the late 19th century. Dialogues devoted to explaining why loving boys is better than loving women go back to antiquity, and are surely far removed from claiming an identity based on an immutable orientation. Philotimes explains his preference for boys as based on reason and experience; his arguments would have had to be quite different if he thought he had no choice about it.

References

Media-BoyWiki

has media related to

Alcibiades

- ↑ Homosexuality in Greece and Rome

- ↑ Alcibiades (character) (Wikipedia)

- ↑ Plato, Alcibiades I p121.

- ↑ The Parallel Lives by Plutarch, The Life of Alcibiades p. 7

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 The story of the Greeks / Hélène Adeline Guerber, p. 160. – 1896.

- ↑ Plutarch, The Parallel Lives The Life of Alcibiades p. 23

- ↑ Alcibiades the Schoolboy (Wikipedia)

- ↑ This review is from: Alcibiades the Schoolboy (Paperback) (amazon.com)

- ↑ Edmund Marlowe's Alexander's Choice