(Boylove Documentary Sourcebook) - On the Homoerotic Poems by Three Early 12th-Century French Catholic Clerics: Difference between revisions

m Dandelion moved page (BLSB) - On the Homoerotic Poems by Three Early 12th-Century French Catholic Clerics to (Boylove Documentary Sourcebook) - On the Homoerotic Poems by Three Early 12th-Century French Catholic Clerics |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

In the Christian milieu of the western European medieval world, poets adopted a wide-range of stances—from the laudatory to the condemnatory—towards same-sex relations. Some monastic writers, however, appear to conflate the two oppositional views, both praising male beauty in highly eroticized terms and damning men who fall to the pleasures of [[Homoerotic (dictionary)|homoerotic]] desire. How is one to understand this apparent contradiction in which the right hand of the poet seems to praise what the left hand proscribes, in which the writer anathematizes what appear to be his own sexual predilections? In this paper, I examine the paradox of holy men expressing unholy desire in reference to three Franco-Latin writers of the early twelfth century: Marbod of Rennes, Baudri of Bourgueil, and Hildebert of Lavardin. Playing at the boundaries between licit and illicit identities, these men speak taboo desire by creating a safe space for themselves through the alternative performances of sinful and of saved personae. The performance of same-sex desire which these men embody serves as yet another sign of the fallen world order; this authorial stance permits the forbidden to be expressed in a manner which paradoxically aligns it with salvation. Thus, the persona—by distancing the author from the desire—becomes the means by which autobiographical reality is simultaneously depicted and rejected. The assumed voice can praise the male form because the sin of desire paradoxically allows both the speaker and the reader to envision themselves as chaste through the redemptive possibilities located in the subsequent rejection of the sin. | In the Christian milieu of the western European medieval world, poets adopted a wide-range of stances—from the laudatory to the condemnatory—towards same-sex relations. Some monastic writers, however, appear to conflate the two oppositional views, both praising male beauty in highly eroticized terms and damning men who fall to the pleasures of [[Homoerotic (dictionary)|homoerotic]] desire. How is one to understand this apparent contradiction in which the right hand of the poet seems to praise what the left hand proscribes, in which the writer anathematizes what appear to be his own sexual predilections? In this paper, I examine the paradox of holy men expressing unholy desire in reference to three [[France|Franco]]-Latin writers of the early twelfth century: Marbod of Rennes, Baudri of Bourgueil, and Hildebert of Lavardin. Playing at the boundaries between licit and illicit identities, these men speak taboo desire by creating a safe space for themselves through the alternative performances of sinful and of saved personae. The performance of same-sex desire which these men embody serves as yet another sign of the fallen world order; this authorial stance permits the forbidden to be expressed in a manner which paradoxically aligns it with salvation. Thus, the persona—by distancing the author from the desire—becomes the means by which autobiographical reality is simultaneously depicted and rejected. The assumed voice can praise the male form because the sin of desire paradoxically allows both the speaker and the reader to envision themselves as chaste through the redemptive possibilities located in the subsequent rejection of the sin. | ||

Such a performance of same-sex desire embodies the individual’s desire and asserts personal objectives and goals antithetical to social conditioning. The twelfth century, which is often discussed in terms of a renaissance, offered poets new opportunities of expression, a new “poetics of authorship,” to use Burt Kimmelman’s term, in which the “medieval poet strives to establish a ground for his or her own singular identity—even though to do so, to assert one’s individuality, will mean having to set aside the authority of the collective, Christian community.” My study differs from preceding works by considering the ways in which the articulation of same-sex desire delineates a specific form of medieval individuality, an individuality which contains itself both inside and outside of western medieval Christianity due to the conflict between sexual desire and theological dictates. | Such a performance of same-sex desire embodies the individual’s desire and asserts personal objectives and goals antithetical to social conditioning. The twelfth century, which is often discussed in terms of a renaissance, offered poets new opportunities of expression, a new “poetics of authorship,” to use Burt Kimmelman’s term, in which the “medieval poet strives to establish a ground for his or her own singular identity—even though to do so, to assert one’s individuality, will mean having to set aside the authority of the collective, Christian community.” My study differs from preceding works by considering the ways in which the articulation of same-sex desire delineates a specific form of medieval individuality, an individuality which contains itself both inside and outside of western medieval Christianity due to the conflict between sexual desire and theological dictates. | ||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

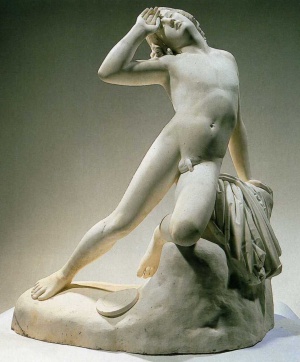

[[File: | [[File:ÉTEX Antoine 1829 Hyacinthe renversé et tué par le palet d'Apollon (1) 1182x1428.jpg|thumb|center|<i>Dying Hyacinth</i> (1829). Marble sculpture by Antoine Étex. Angers, Musée des beaux-arts.]] | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 138: | Line 138: | ||

*[[Pederasty]] | *[[Pederasty]] | ||

*[[Pedophilia]] | *[[Pedophilia]] | ||

*[[Situational homosexuality (dictionary)]] | |||

*[[Young friend (dictionary)]] | *[[Young friend (dictionary)]] | ||

| Line 144: | Line 145: | ||

*[https://greek-love.com/europe-5th-17th-centuries/the-poems-of-marbod-of-rennes THE GREEK LOVE POEMS OF MARBOD OF RENNES (Greek Love Through the Ages)] | *[https://greek-love.com/europe-5th-17th-centuries/the-poems-of-marbod-of-rennes THE GREEK LOVE POEMS OF MARBOD OF RENNES (Greek Love Through the Ages)] | ||

[[Category:Boylove Sourcebook]] | [[Category:Boylove Documentary Sourcebook]] | ||

[[Category:France]] | [[Category:France]] | ||

[[Category:Medieval Latin literature]] | [[Category:Medieval Latin literature]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:25, 3 November 2021

From "Personae, Same-Sex Desire, and Salvation in the Poetry of Marbod of Rennes, Baudri of Bourgueil, and Hildebert of Lavardin" by Tison Pugh, in Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Vol. 31, No. 1 (2000). Footnotes omitted.

“Luxuriae vitio castissimus en ego fio,

Quod duros mollit, hoc molitiem mihi tollit.”

Marbod of Rennes

(“Lo, I am made completely chaste by the sin

of lechery. / [The vice] which makes hard men

soft takes away my softness.”)

In the Christian milieu of the western European medieval world, poets adopted a wide-range of stances—from the laudatory to the condemnatory—towards same-sex relations. Some monastic writers, however, appear to conflate the two oppositional views, both praising male beauty in highly eroticized terms and damning men who fall to the pleasures of homoerotic desire. How is one to understand this apparent contradiction in which the right hand of the poet seems to praise what the left hand proscribes, in which the writer anathematizes what appear to be his own sexual predilections? In this paper, I examine the paradox of holy men expressing unholy desire in reference to three Franco-Latin writers of the early twelfth century: Marbod of Rennes, Baudri of Bourgueil, and Hildebert of Lavardin. Playing at the boundaries between licit and illicit identities, these men speak taboo desire by creating a safe space for themselves through the alternative performances of sinful and of saved personae. The performance of same-sex desire which these men embody serves as yet another sign of the fallen world order; this authorial stance permits the forbidden to be expressed in a manner which paradoxically aligns it with salvation. Thus, the persona—by distancing the author from the desire—becomes the means by which autobiographical reality is simultaneously depicted and rejected. The assumed voice can praise the male form because the sin of desire paradoxically allows both the speaker and the reader to envision themselves as chaste through the redemptive possibilities located in the subsequent rejection of the sin.

Such a performance of same-sex desire embodies the individual’s desire and asserts personal objectives and goals antithetical to social conditioning. The twelfth century, which is often discussed in terms of a renaissance, offered poets new opportunities of expression, a new “poetics of authorship,” to use Burt Kimmelman’s term, in which the “medieval poet strives to establish a ground for his or her own singular identity—even though to do so, to assert one’s individuality, will mean having to set aside the authority of the collective, Christian community.” My study differs from preceding works by considering the ways in which the articulation of same-sex desire delineates a specific form of medieval individuality, an individuality which contains itself both inside and outside of western medieval Christianity due to the conflict between sexual desire and theological dictates.

[...]

Marbod of Rennes depicts same-sex desire in terms of enthusiastic acceptance and approval in some poems but with disgust and loathing in others, and his lyrics often highlight that he is writing to and among a community of like-minded men. In his poetry, Marbod often concentrates on the sexual favors granted by boys to their lovers, and he presents these relationships openly and without any embarrassment. In “Ad amicum absentem” (“To an Absent Friend”), the narrator admonishes a friend to hasten home so that his boy will not be tempted to leave him for another:

Perdes in hac villa plusquam lucraris in illa:

Namque quid tanti, quanti puer aequus amanti?

Qui nunc est aequus, fiat mora, fiet iniquus.

Blanditiis siquidem tentatur pluribus idem;

Et qui tentatur, metus est ne decipiatur.(You are losing more in this town than you are getting in that one. / For what is as precious as a boy who is fair with his lover? / Now he is even-tempered [but if] a delay is made, he will be made wicked. / Indeed, he is assailed with many flatteries, / And [if] he can be tempted, there is a fear that he could be beguiled.)

As the speaker offers advice to his friend, the poem addresses same-sex desire in a matter-of-fact tone. No hint of censure of same-sex relationships appears; the only fear expressed is that same-sex desire will be frustrated rather than realized. The poem also hints that there are a wide range of sexual partners for the boy through its reference to the “blanditiis . . . pluribis” (“many enticements”). This passage indicates that same-sex desire and activity runs rampant throughout the boy’s community.

Marbod’s lyrics of same-sex love concentrate sexual attention on boys rather than men. In the poems, boys are depicted as the object of sexual attraction, but their prized status is threatened by the approach of age and maturity which will render them bereft of their beauty. Marbod thus admonishes the object of his affection in “Satyra in amatorem puelli sub assumpta persona” (“A Satire on the Lover of a Boy in an Assumed Persona”) to take advantage of sexual opportunities now because they will disappear when age takes its toll upon his fair flesh:

Haec caro tam levis, tam lactea, tam sine naevis,

Tam bona, tam bella, tam lubrica, tamque tenella.

Tempus adhuc veniet, cum turpis et hispida fiet:

Cum fiet vilis caro chara caro puerilis.

Ergo dum flores, maturos indue mores.

Dum potes et peteris, cupido dare ne pigriteris.(This flesh is so smooth, so milky, without moles, / So good, so pretty, so smooth, and so tender. / But the time will come when it will become base and coarse, / When [this] dear flesh, [this] boyish flesh will become vile. / Therefore, while you flourish, take up mature customs. / While you are able and you are sought, do not be slow to give [yourself] to a lover.)

The poem stresses the necessity of seizing earthly and sensual—rather than heavenly and spiritual—delights. As time will deprive the boy of his sexual attractiveness, he should enjoy these pleasures when they are so readily available. This poetic trope of carpe diem in youth appears frequently in pre-medieval homoerotic verse; as Norman Roth observes, “The theme of the adolescent whose approaching adulthood, signaled by the appearance of down on the cheek, brought an end to his desirability as an object of love was common in Greek, Arabic, and Hebrew poetry.”

In “Satyra in amatorem puelli sub assumpta persona,” Marbod describes the boy’s body in a highly sensualized and detailed manner. The words paint a vision of mortal beauty as the speaker’s descriptions move from the top of the boy’s head to his beautiful body below, ending with the poet’s account of what anyone would want to do with such a boy with such a body:

Undabant illi per eburnea colla capilli,

Candida frons ut nix, et lumina nigra velut pix,

Implumesque genae grata dulcedine plenae,

Cum in candoris vernabant luce ruboris.

Nasus erat justus, labra flammea, densque venustus.

Effigies menti modulo formata decenti.

Qui corpus quaeret quod tectum veste lateret,

Tale coaptet ei quod conveniat faciei.(Over [his] ivory neck flowed his hair, / [His] forehead [was] white as snow, and [his] eyes black as pitch; / His hairless cheeks full of pleasing sweetness / When they bloomed in the light of the radiance of red. / His nose was straight, lips fiery, and teeth lovely, / The shape of [his] chin formed from a suitable model. / Anyone seeking the body which was hidden, covered by [his] clothes / Would find it comparable to that face it matches.)

This passage’s luminous description of the boy’s body is reminiscent of the imagery found in the Song of Songs’ catalogue of the beloved’s features in which the colors of ivory, red, and black highlight his beauty; the biblical vision of unity between heterosexual lovers, which is commonly allegorized into the relationship between Christ and his church in the medieval period, is here transformed into a paean to same-sex desire. Also, the narrator’s personal involvement with the boy is evident through the use of first-person narration; the lyric voice delineates his personal fascination with the male form. And although the speaker revels in his own appreciation of the boy’s body, his declaration that others would find the boy equally attractive again suggests a community of men who would find such a boy sexually desirable.

[...]

Baudri of Bourgueil’s poetry evinces a similar thematic dichotomy in his considerations of same-sex desire. In “Ad juvenem nimis elatum” (“To a Youth Too Proud”), the narrative voice portrays the rapturous effects of the boy’s body upon him and his own tactile responses to it. No traces of remonstration mar the encomium to same-sex desire:

Forma placet, quia forma decet, quia forma venusta est:

Mala tenella placet, flavum caput osque modestum . . .

His bene respondet caro lactea, pectus eburnum.

Alludit manibus niveo de corpore tactus.

Haec sunt quae debent aliisque mihique placere,

Praesertim cum te nec agat lasciva juventus

Nec reprobet divam membrorum composituram.

Haec mihi cuncta placent, haec et mihi singula mando.([Your] appearance is pleasing because it is a proper appearance, because it is a beautiful appearance; / [Your] tender cheek is pleasing, [as are your] golden head and modest mouth. / . . . / Your milky flesh and ivory chest agree with these features; / The touch of your snow-white body plays with my hands. / These are the things which ought to please others and me, / Especially since licentious youth does not control you / Or condemn the divine composition of your limbs. / All these are pleasing to me: I commend each one to myself.)

The lyric voice of the speaker claims the pleasures of the boy’s body for himself. The passion for the male body, expressed in terms of fleshly fascination rather than spiritual salvation, is a key theme to Baudri’s poetry, and, as Gerald Bond notes, “one cannot escape the conclusion that Baudri intentionally evoked homosexual relationships in many of his poems by discussing amor between males in a context devoid of explicit Christian values.” Focusing on fleshly and earthly delights, Baudri concentrates on tactile pleasures rather than fraternal chastity. Indeed, fraternal chastity appears outside of Baudri’s world view, as he underscores the fact that the boy’s body should not only please himself, but others as well.

[...]

Another of Hildebert’s lyrics which expresses an accepting attitude toward same-sex desire is set in the mythology of the classical past as well. Similar to “Cum peteret puerum,” his “Phoebus de interitu Hyacinthi” (“Phoebus on the death of Hyacinth”) contains its depiction of same-sex love within Greek mythology. The poem describes Phoebus’s tragic despair at the death of his beloved Hyacinth:

Et deus et medicus et amans, rescindere frustra

Tentans Aebalidae funera, Phoebus ait:

“Parcite, di, puero, si non moriatur uterque;

Malo sequi puerum quam superesse deum.

Si prohibetis et hoc, sit pars utriusque superstes,

Par cadit, ignoscam sic minor esse deo.

Quisque feret laetus propriae dispendia partis,

Dum pars ad manes, pars eat ad superos.”(God and doctor and lover, in vain trying to take back / The funeral of Oebalus’s son, Phoebus says: / “Gods, spare the boy. If [we] both won’t die, / I prefer to follow the boy than to survive as a god. / And if you prohibit this, may a part of each [of us] survive, / A part fall. Thus, I would pardon that I was less than a god. / Each [of us] would happily bear the cost of a near part, / While a part [of us] went to the shadows, a part [of us] would go to the heavens.”)

Offering to share both suffering and pleasure, the underworld and the heavens, Phoebus pleads for his love at any cost. Hildebert’s depiction of the doomed love stresses with eloquence and compassion the emotional pain experienced when male lovers are separated.

See also

- Adult friend (dictionary)

- Age of attraction (dictionary)

- Boylove

- Ephebophilia

- Loved boy (dictionary)

- Minor-attracted person (dictionary)

- Pederasty

- Pedophilia

- Situational homosexuality (dictionary)

- Young friend (dictionary)