(Boylove Documentary Sourcebook) - An Excerpt from "Offences Against One's Self: Paederasty" by Jeremy Bentham: Difference between revisions

Dandelion moved page (BLSB) - An Excerpt from "Offences Against One's Self: Paederasty" by Jeremy Bentham to An Excerpt from "Offences Against One's Self: Paederasty" by Jeremy Bentham Tag: New redirect |

m Dandelion moved page (BLSB) - An Excerpt from "Offences Against One's Self: Paederasty" by Jeremy Bentham to (Boylove Documentary Sourcebook) - An Excerpt from "Offences Against One's Self: Paederasty" by Jeremy Bentham |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Jeremy Bentham by Henry William Pickersgill.png|thumb|center|<i>Jeremy Bentham</i> (exhibited in 1829) by Henry William Pickersgill. Oil on canvas, 204.4 × 138.4 cm (London, [[United Kingdom]]: National Portrait Gallery).]] | |||

From "Offences Against One's Self: [[Pederasty|Paederasty]]. Part 1" (c. 1785) by Jeremy Bentham, edited by Louis Crompton, in <i>Journal of [[Homosexuality]]</i>, Vol. 3, No. 4 (1978). | |||

<div style="margin:.5em auto; width:95%; min-height:5em; background-color:#F5FAFF; border:3px solid #c9c9ff; padding:1em;"> | |||

<i>ABSTRACT: This is the first publication of Jeremy Bentham’s essay on “Paederasty,” written about 1785. The essay, which runs to over 60 manuscript pages, is the first known argument for homosexual law reform in England. Bentham advocates the decriminalization of [[sodomy]], which in his day was punished by hanging. He argues that homosexual acts do not “weaken” men, or threaten population or marriage, and documents their prevalence in [[ancient Greece]] and [[Ancient Rome|Rome]]. Bentham opposes punishment on utilitarian grounds and attacks ascetic sexual morality. In the preceding article the editor’s introduction discussed the essay in the light of 18th-century legal opinion and quoted Bentham’s manuscript notes that reveal his anxieties about expressing his views.</i> | |||

---- | |||

To what class of offences shall we refer these irregularities of the venereal appetite which are stiled unnatural? When hidden from the public eye there could be no colour for placing them any where else: could they find a place any where it would be here. I have been tormenting myself for years to find if possible a sufficient ground for treating them with the severity with which they are treated at this time of day by all European nations: but upon the principle of utility I can find none. | |||

<i>Offences of impurity—their varieties</i> | |||

The abominations that come under this heading have this property in common, in this respect, that they consist in procuring certain sensations by means of an improper object. The impropriety then may consist either in making use of an object | |||

1. Of the proper species but at an improper time: for instance, after death.<br> | |||

2. Of an object of the proper species and sex, and at a proper time, but in an improper part.<br> | |||

3. Of an object of the proper species but the wrong sex. This is distinguished from the rest by the name of paederasty.<br> | |||

4. Of a wrong species.<br> | |||

5. In procuring this sensation by one’s self without the help of any other sensitive object. | |||

<i>Paederasty makes the greatest figure</i> | |||

The third being that which makes the most figure in the world it will be proper to give that the principal share of our attention. In settling the nature and tendency of this offence we shall for the most part have settled the nature and tendency of all the other offences that come under this disgusting catalogue. / | |||

<i>Whether they produce any primary mischief</i> | |||

1. As to any primary mischief, it is evident that it produces no pain in anyone. On the contrary it produces pleasure, and that a pleasure which, by their perverted taste, is by this supposition preferred to that pleasure which is in general reputed the greatest. The partners are both willing. If either of them be unwilling, the act is not that which we have here in view: it is an offence totally different in its nature of effects: it is a personal injury; it is a kind of rape. | |||

<i>As a secondary mischief whether they produce any alarm in the community</i> | |||

2. As to any secondary mischief, it produces not any pain of apprehension. For what is there in it for any body to be afraid of? By the supposition, those only are the objects of it who choose to be so, who find a pleasure, for so it seems they do, in being so. | |||

<i>Whether any danger</i> | |||

3. As to any danger exclusive of pain, the danger, if any, must consist in the tendency of the example. But what is the tendency of this example? To dispose others to engage in the same practises: but this practise for anything that has yet appeared produces not pain of any kind to any one. | |||

<i>Reasons that have commonly been assigned</i> | |||

Hitherto we have found no reason for punishing it at all: much less for punishing it with the degree of severity with which it has been commonly punished. Let us see what force there is in the reasons that have been commonly assigned for punishing it. | |||

[...] | |||

<i>Whether it robs women</i> | |||

A more serious imputation for punishing this practise [is] that the effect of it is to produce in the male sex an indifference to the female, and thereby defraud the latter of their rights. | |||

[...] | |||

The question then is reduced to this. What are the number of women who by the prevalence of this taste would, it is probable, be prevented from getting husbands? These and these only are they who would be sufferers by it. Upon the following considerations it does not seem likely that the prejudice sustained by the sex in this way could ever rise to any considerable amount. Were the prevalence of this taste to rise to ever so great a height the most considerable part of the motives to marriage would remain entire. In the first place, the desire of having children, in the next place the desire of forming alliances between families, thirdly the convenience of having a domestic companion whose company will continue to be / agreeable throughout life, fourthly the convenience of gratifying the appetite in question at any time when the want occurs and without the expense and trouble of concealing it or the danger of a discovery. | |||

Were a man’s taste even so far corrupted as to make him prefer the embraces of a person of his own sex to those of a female, a connection of that preposterous kind would therefore be far enough from answering to him the purposes of a marriage. A connection with a woman may by accident be followed with disgust, but a connection of the other kind, a man must know, will for certain come in time to be followed by disgust. All the documents we have from the antients relative to this matter, and we have a great abundance, agree in this, that it is only for a very few years of his life that a male continues an object of desire even to those in whom the infection of this taste is at the strongest. The very name it went by among the Greeks may stand instead of all other proofs, of which the works of Lucian and Martial alone will furnish any abundance that can be required. Among the Greeks it was called <i>Paederastia</i>, the love of boys, not <i>Andrerastia</i>, the love of men. Among the Romans the act was called Paedicare because the object of it was a boy. There was a particular name for those who had past the short period beyond which no man hoped to be an object of desire to his own sex. They were called <i>exoleti</i>. No male therefore who was passed this short period of life could expect to find in this way any reciprocity of affection; he must be as odious to the boy from the beginning as in a short time the boy would be to him. The objects of this kind of sensuality would therefore come only in the place of common prostitutes; they could never even to a person of this depraved taste answer the / purposes of a virtuous woman. | |||

</div> | |||

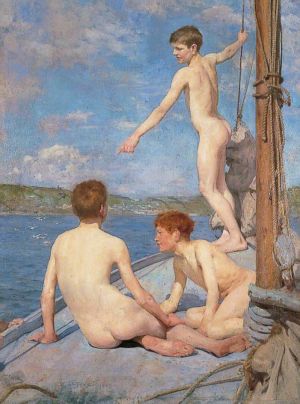

[[File:TUKE Henry Scott 1888c The bathers 701x944.jpg|thumb|center|<i>The Bathers</i> (1889) by Henry Scott Tuke. Oil on canvas, 116.8 × 86.3 cm (Leeds, United Kingdom: Leeds Art Gallery.]] | |||

==External links== | |||

*[http://columbia.edu/cu/lweb/eresources/exhibitions/sw25/bentham/ <i>Offences Against One's Self</i> by Jeremy Bentham (Stonewall and Beyond: Lesbian and Gay Culture - Columbia University Libraries)] | |||

*[https://greek-love.com/general-non-fiction-pederasty/bentham-jeremy-offences-against-oneself-paederasty <i>OFFENCES AGAINST ONE'S SELF: PAEDERASTY</i> BY JEREMY BENTHAM (Greek Love Through the Ages)] | |||

[[Category:Boylove Documentary Sourcebook]] | |||

[[Category:United Kingdom]] | |||

[[Category:Essayistic literature]] | |||

[[Category:Philosophy]] | |||

[[Category:Sexuality]] | |||

[[Category:LGBT articles]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:17, 3 November 2021

From "Offences Against One's Self: Paederasty. Part 1" (c. 1785) by Jeremy Bentham, edited by Louis Crompton, in Journal of Homosexuality, Vol. 3, No. 4 (1978).

ABSTRACT: This is the first publication of Jeremy Bentham’s essay on “Paederasty,” written about 1785. The essay, which runs to over 60 manuscript pages, is the first known argument for homosexual law reform in England. Bentham advocates the decriminalization of sodomy, which in his day was punished by hanging. He argues that homosexual acts do not “weaken” men, or threaten population or marriage, and documents their prevalence in ancient Greece and Rome. Bentham opposes punishment on utilitarian grounds and attacks ascetic sexual morality. In the preceding article the editor’s introduction discussed the essay in the light of 18th-century legal opinion and quoted Bentham’s manuscript notes that reveal his anxieties about expressing his views.

To what class of offences shall we refer these irregularities of the venereal appetite which are stiled unnatural? When hidden from the public eye there could be no colour for placing them any where else: could they find a place any where it would be here. I have been tormenting myself for years to find if possible a sufficient ground for treating them with the severity with which they are treated at this time of day by all European nations: but upon the principle of utility I can find none.

Offences of impurity—their varieties

The abominations that come under this heading have this property in common, in this respect, that they consist in procuring certain sensations by means of an improper object. The impropriety then may consist either in making use of an object

1. Of the proper species but at an improper time: for instance, after death.

2. Of an object of the proper species and sex, and at a proper time, but in an improper part.

3. Of an object of the proper species but the wrong sex. This is distinguished from the rest by the name of paederasty.

4. Of a wrong species.

5. In procuring this sensation by one’s self without the help of any other sensitive object.

Paederasty makes the greatest figure

The third being that which makes the most figure in the world it will be proper to give that the principal share of our attention. In settling the nature and tendency of this offence we shall for the most part have settled the nature and tendency of all the other offences that come under this disgusting catalogue. /

Whether they produce any primary mischief

1. As to any primary mischief, it is evident that it produces no pain in anyone. On the contrary it produces pleasure, and that a pleasure which, by their perverted taste, is by this supposition preferred to that pleasure which is in general reputed the greatest. The partners are both willing. If either of them be unwilling, the act is not that which we have here in view: it is an offence totally different in its nature of effects: it is a personal injury; it is a kind of rape.

As a secondary mischief whether they produce any alarm in the community

2. As to any secondary mischief, it produces not any pain of apprehension. For what is there in it for any body to be afraid of? By the supposition, those only are the objects of it who choose to be so, who find a pleasure, for so it seems they do, in being so.

Whether any danger

3. As to any danger exclusive of pain, the danger, if any, must consist in the tendency of the example. But what is the tendency of this example? To dispose others to engage in the same practises: but this practise for anything that has yet appeared produces not pain of any kind to any one.

Reasons that have commonly been assigned

Hitherto we have found no reason for punishing it at all: much less for punishing it with the degree of severity with which it has been commonly punished. Let us see what force there is in the reasons that have been commonly assigned for punishing it.

[...]

Whether it robs women

A more serious imputation for punishing this practise [is] that the effect of it is to produce in the male sex an indifference to the female, and thereby defraud the latter of their rights.

[...]

The question then is reduced to this. What are the number of women who by the prevalence of this taste would, it is probable, be prevented from getting husbands? These and these only are they who would be sufferers by it. Upon the following considerations it does not seem likely that the prejudice sustained by the sex in this way could ever rise to any considerable amount. Were the prevalence of this taste to rise to ever so great a height the most considerable part of the motives to marriage would remain entire. In the first place, the desire of having children, in the next place the desire of forming alliances between families, thirdly the convenience of having a domestic companion whose company will continue to be / agreeable throughout life, fourthly the convenience of gratifying the appetite in question at any time when the want occurs and without the expense and trouble of concealing it or the danger of a discovery.

Were a man’s taste even so far corrupted as to make him prefer the embraces of a person of his own sex to those of a female, a connection of that preposterous kind would therefore be far enough from answering to him the purposes of a marriage. A connection with a woman may by accident be followed with disgust, but a connection of the other kind, a man must know, will for certain come in time to be followed by disgust. All the documents we have from the antients relative to this matter, and we have a great abundance, agree in this, that it is only for a very few years of his life that a male continues an object of desire even to those in whom the infection of this taste is at the strongest. The very name it went by among the Greeks may stand instead of all other proofs, of which the works of Lucian and Martial alone will furnish any abundance that can be required. Among the Greeks it was called Paederastia, the love of boys, not Andrerastia, the love of men. Among the Romans the act was called Paedicare because the object of it was a boy. There was a particular name for those who had past the short period beyond which no man hoped to be an object of desire to his own sex. They were called exoleti. No male therefore who was passed this short period of life could expect to find in this way any reciprocity of affection; he must be as odious to the boy from the beginning as in a short time the boy would be to him. The objects of this kind of sensuality would therefore come only in the place of common prostitutes; they could never even to a person of this depraved taste answer the / purposes of a virtuous woman.