Nenja: Difference between revisions

Added a missing blank space to the first paragraph of the article |

Replaced a word in the first paragraph of the article, and added a reference |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

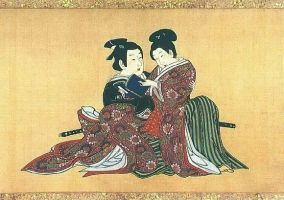

[[File: | [[File:Miyagawa Isshô-Spring Pastimes-A.jpg|284px|right|<i>Nanshoku</i>-type tryst between a samurai and a boyfriend. Panel from <i>Spring Pastimes</i> (ca. 1750), a series of ten homoerotic scenes by Miyagawa Isshō. <i>Shunga</i>-style painted hand scroll (<i>kakemono-e</i>); <i>sumi</i>, color and <i>gofun</i> on silk. Private collection.]] | ||

'''Nenja''' (念者, "lover" or "admirer"), in premodern [[Japan]], was a term applied to the older and sexually active male partner involved in a [[Homoerotic (dictionary)|homoerotic]] relationship with a ''[[wakashū]]'' (若衆, "youth"), a sexually passive [[Adolescence|adolescent]] boy, in the context of the historical practice of ''[[shudō]]'' (衆道, "the way of youths"), also known as ''[[nanshoku]]'' (男色, "male love"), which was customary among members of the Buddhist clergy and of the [[samurai]] class. | |||

'''Nenja''' (念者, "lover" or "admirer"), in premodern [[Japan]], was a term applied to the older and sexually active male partner involved in a [[Homoerotic (dictionary)|homoerotic]] relationship with a ''[[wakashū]]'' (若衆, "youth"), a sexually passive [[Adolescence|adolescent]] boy, in the context of the historical practice of ''[[shudō]]'' (衆道, "the way of youths"), also known as ''[[nanshoku]]'' (男色, "male love"), which was customary among members of the Buddhist clergy and of the [[samurai]] nobility, and later adopted by some individuals of the wealthy merchant class.<ref>Gary P. Leupp, ''Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), pp. 56–57 and 61.</ref> | |||

The sense of the word can be rendered as "a person who thinks of a particular youth", the character ''nen'' (念) being of difficult translation, as its meaning falls somewhere between rational "thinking" and emotive "feeling". Unlike the term ''wakashū'', its counterpart ''nenja'' had no age signifier, although it was expected in principle that the lover would be older than his beloved.<ref>Gregory M. Pflugfelder, ''Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600–1950'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. 36.</ref> | The sense of the word can be rendered as "a person who thinks of a particular youth", the character ''nen'' (念) being of difficult translation, as its meaning falls somewhere between rational "thinking" and emotive "feeling". Unlike the term ''wakashū'', its counterpart ''nenja'' had no age signifier, although it was expected in principle that the lover would be older than his beloved.<ref>Gregory M. Pflugfelder, ''Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600–1950'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. 36.</ref> | ||

Latest revision as of 02:06, 25 September 2021

Nenja (念者, "lover" or "admirer"), in premodern Japan, was a term applied to the older and sexually active male partner involved in a homoerotic relationship with a wakashū (若衆, "youth"), a sexually passive adolescent boy, in the context of the historical practice of shudō (衆道, "the way of youths"), also known as nanshoku (男色, "male love"), which was customary among members of the Buddhist clergy and of the samurai nobility, and later adopted by some individuals of the wealthy merchant class.[1]

The sense of the word can be rendered as "a person who thinks of a particular youth", the character nen (念) being of difficult translation, as its meaning falls somewhere between rational "thinking" and emotive "feeling". Unlike the term wakashū, its counterpart nenja had no age signifier, although it was expected in principle that the lover would be older than his beloved.[2]

References

- ↑ Gary P. Leupp, Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), pp. 56–57 and 61.

- ↑ Gregory M. Pflugfelder, Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600–1950 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. 36.