Nenja: Difference between revisions

Modified the second paragraph of the article |

Added information to the first paragraph of the article |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

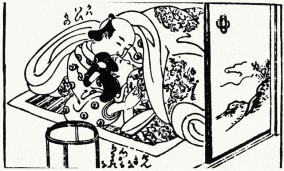

[[File:Nishikawa Sukenobu - Male couple lying down together. Japanese woodblock-printed illustration from Nanshoku Yamaji no Tsuyu by Nankai no Sanjin, early 18th century.png|284px|thumb|right|Male couple: A ''nenja'' and a ''wakashū'' lying down together. Japanese woodblock-printed illustration by Nishikawa Sukenobu, from ''Nanshoku Dew on a Mountain Path'' (男色山路露 ''Nanshoku Yamaji no Tsuyu'', Early 18th Century) by Nankai no Sanjin.]] | [[File:Nishikawa Sukenobu - Male couple lying down together. Japanese woodblock-printed illustration from Nanshoku Yamaji no Tsuyu by Nankai no Sanjin, early 18th century.png|284px|thumb|right|Male couple: A ''nenja'' and a ''wakashū'' lying down together. Japanese woodblock-printed illustration by Nishikawa Sukenobu, from ''Nanshoku Dew on a Mountain Path'' (男色山路露 ''Nanshoku Yamaji no Tsuyu'', Early 18th Century) by Nankai no Sanjin.]] | ||

'''Nenja''' (念者, "lover" or "admirer"), in premodern [[Japan]], was a term applied to the older and sexually active male partner involved in a [[Homoerotic (dictionary)|homoerotic]] relationship with a ''[[wakashū]]'' (若衆, "youth"), a sexually passive [[Adolescence|adolescent]] boy, in the context of the historical practice of ''[[shudō]]'' (衆道,"the way of youths"), also known as ''[[nanshoku]]'' (男色, "male love"). | '''Nenja''' (念者, "lover" or "admirer"), in premodern [[Japan]], was a term applied to the older and sexually active male partner involved in a [[Homoerotic (dictionary)|homoerotic]] relationship with a ''[[wakashū]]'' (若衆, "youth"), a sexually passive [[Adolescence|adolescent]] boy, in the context of the historical practice of ''[[shudō]]'' (衆道,"the way of youths"), also known as ''[[nanshoku]]'' (男色, "male love"), which was customary among members of the Buddhist clergy and of the [[samurai]] class. | ||

The sense of the word can be rendered as "a person who thinks of a particular youth", the character ''nen'' (念) being of difficult translation, as its meaning falls somewhere between rational "thinking" and emotive "feeling". Unlike the term ''wakashū'', its counterpart ''nenja'' had no age signifier, although it was expected in principle that the lover would be older than his beloved.<ref>Gregory M. Pflugfelder, ''Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600–1950'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. 36.</ref> | The sense of the word can be rendered as "a person who thinks of a particular youth", the character ''nen'' (念) being of difficult translation, as its meaning falls somewhere between rational "thinking" and emotive "feeling". Unlike the term ''wakashū'', its counterpart ''nenja'' had no age signifier, although it was expected in principle that the lover would be older than his beloved.<ref>Gregory M. Pflugfelder, ''Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600–1950'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. 36.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 11:44, 18 August 2021

Nenja (念者, "lover" or "admirer"), in premodern Japan, was a term applied to the older and sexually active male partner involved in a homoerotic relationship with a wakashū (若衆, "youth"), a sexually passive adolescent boy, in the context of the historical practice of shudō (衆道,"the way of youths"), also known as nanshoku (男色, "male love"), which was customary among members of the Buddhist clergy and of the samurai class.

The sense of the word can be rendered as "a person who thinks of a particular youth", the character nen (念) being of difficult translation, as its meaning falls somewhere between rational "thinking" and emotive "feeling". Unlike the term wakashū, its counterpart nenja had no age signifier, although it was expected in principle that the lover would be older than his beloved.[1]

References

- ↑ Gregory M. Pflugfelder, Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600–1950 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. 36.