Shudō: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

==Cultural aspects== | ==Cultural aspects== | ||

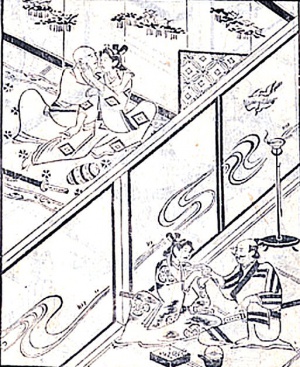

[[ | [[File:Japanesepederasty18thcentury.jpg|left|thumb|250px|18th Century Japanese print of a man with his young male lover who is sneaking a kiss with a female prostitute.]] | ||

The teachings of shudo, "The Way of the Young", entered the literary tradition and can be found in such as works as [[Hagakure]] (葉隠), "Hidden by Leaves", and other [[samurai]] manuals. Shudo, in its pedagogic, martial, and aristocratic aspects, is closely analogous to the ancient Greek tradition of [[pederasty]]. | The teachings of shudo, "The Way of the Young", entered the literary tradition and can be found in such as works as [[Hagakure]] (葉隠), "Hidden by Leaves", and other [[samurai]] manuals. Shudo, in its pedagogic, martial, and aristocratic aspects, is closely analogous to the ancient Greek tradition of [[pederasty]]. | ||

Revision as of 15:50, 2 July 2015

Template:Nihongo is the Japanese tradition of age-structured homosexuality or pederasty prevalent in samurai society from the medieval period until the end of the 19th century. The word is an abbreviation of wakashudō (若衆道), "the way of the young" or more precisely, "the way of young (若 waka) men (衆 shū)". The "dō" (道) is related to the Chinese word tao, considered to be a structured discipline and body of knowledge, as well as a path to awakening.

The older partner in the relationship was known as the nenja (念者), and the younger as the wakashū (若衆).

Origins

Though the term shudo first appears in 17th century, it is preceded in the Japanese homosexual tradition by the love relationships between bonzes and their acolytes, who were known as chigo. The legendary supposed founder of male love in Japan is Kūkai, also known as Kōbō Daishi, the founder of the Shingon school of thought who is said to have brought over from the mainland, together with the teachings of the Shingon, the teachings of male love. [1] Mount Kōya, where Kōbō Daishi's monastery is still located, was a byword for male love up to the end of the pre-modern period.[Citation needed]

Despite the attribution of male love to Kūkai, references to male love can be found in some of the earliest Japanese texts, such as the 8th century history "Kojiki" (古事記) and the "Nihon Shoki" (日本書紀).

Cultural aspects

The teachings of shudo, "The Way of the Young", entered the literary tradition and can be found in such as works as Hagakure (葉隠), "Hidden by Leaves", and other samurai manuals. Shudo, in its pedagogic, martial, and aristocratic aspects, is closely analogous to the ancient Greek tradition of pederasty.

The practice was held in high esteem, and was encouraged, especially within the samurai class. It was considered beneficial for the youth, teaching him virtue, honesty and the appreciation of beauty. Its value was contrasted with the love of women, which was blamed for feminizing men.[Citation needed]

Much of the historical and fictional literature of the period praised the beauty and valor of boys faithful to shudo. The modern historian Jun'ichi Iwata drew up a list of 457 such titles from the 17th and 18th centuries alone, considered a "corpus of erotic pedagogy." (Watanabe & Iwata, 1989)

With the rise in power and influence of the merchant class, aspects of the practice of shudo were adopted by the middle classes, and homoerotic expression in Japan began to be more closely associated with travelling kabuki actors known as tobiko ( 飛子) , "fly boys," who moonlighted as prostitutes.

In the Edo period (1600-1868), kabuki actors (known as onnagata when playing female roles) often worked as prostitutes off-stage. Kagema were male prostitutes who worked at specialist brothels called "kagemajaya" (陰間茶屋: kagema tea houses). Both kagema and kabuki actors were much sought after by the sophisticates of the day, who often practiced danshoku/nanshoku, or male love.

Beginning with the Meiji restoration and the rise of Western influence, Christianity began to influence the culture, leading to a rapid decline of sanctioned homoerotic practices in the late 1800s.[Citation needed] [2]

See also

- Homosexuality in Japan

- Homosexuality and Buddhism

- Nanshoku (男色, Male Color)

- Pederastic couples in Japan

- Pederasty

- Shonen-ai

References

- ↑ 井原西鶴, Ihara Saikaku. (Paul Gordon Schalow, trans.). The Great Mirror of Male Love. Stanford University Press, 1990.

- ↑ Kaku, Sechiyama. "Rainbow in the East: LGBT Rights in Japan." Nippon. Nippon Communications Foundation, 28 May 2015. Web. 29 June 2015.

Further reading

- Leupp, Gary. Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press, 1997.

- Pflugfelder, Gregory. Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600-1950. University of California Press, 2000.

- Iwata, Junʾichi; Watanabe, Tsuneo (1989). Love of the Samurai: a thousand years of Japanese homosexuality. London: Gay Men's Press. ISBN 0-85449-115-5.

External links

Page to be merged

Shudō was a samurai custom in which adult samurai engaged in pederastic relationships with younger samurai. This custom is most prominently seen, or discussed, in the Sengoku and Edo periods.[1]

The older man in the relationship, known as the nenja (念者), and the younger man, known by a variety of terms including wakashû (若衆), formed a close, tight personal relationship with one another. A nenja typically engaged in such relationships with only one wakashû at a time, and vice versa. Though much discussion today, based in modern/Western social mores about homosexual relationships, focus strongly on the homosexual sexual acts involved in the relationship, shudô relationships went beyond this, and were strong personal and sentimental or emotional relationships, which involved as well strong elements of mentorship. Mentorship and training in the "warrior" lifestyle and values of the samurai was a major element of the relationship.

From the medieval period, if not earlier, the Japanese considered homosexual acts and relationships as simply a matter of taste or preference, and as something which simply varied from person to person, and over time. While Confucian teachings place a strong emphasis on family, and on proper relationships with one's parents, spouse, and children, there was no parallel in Japanese tradition to the biblical bans on such activities. The specific mode of shûdô male-male relationships, particular to the samurai class, emerged in the medieval period, and by the Edo period was likely seen as a firmly entrenched traditional custom.[2]

References

- Maki Morinaga, "The Gender of Onnagata as the Imitating Imitated," positions 10:2 (2002), 245-284.

- ↑ The Samurai-Archives Samurai Wiki

- ↑ Eiko Ikegami, Bonds of Civility, Cambridge University Press (2005), 269-270