Alcibiades

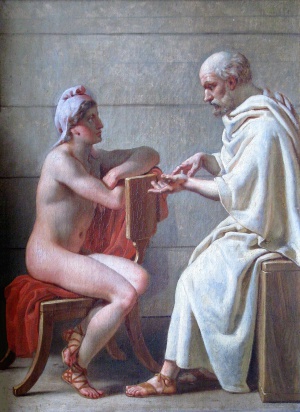

Alcibiades, son of Cleinias, from the deme of Scambonidae (/ˌælsɨˈbaɪ.ədiːz/; Greek: Ἀλκιβιάδης Κλεινίου Σκαμβωνίδης, transliterated Alkibiádēs Kleiníou Skambōnidēs; c. 450 – 404 BC) historically was a Greek statesman and general. However, he has been best known posthumously as a disciple and especially the boy love (eromenos) of Socrates. This is clearly seen in Plutarch's life of Alcibiades [1], and in Plato's better-known Symposium. He has been, in post-Renaissance times, a coded symbol of pederasty. [2]

Alcibiades the Schoolboy

Alcibiades the Schoolboy (L'Alcibiades, fanciullo a scola) by Antonio Rocco writen in the 17th century is a fictional dialogue in which Socrates which portrays the excellence of sexual love between master and (male) disciple. Wikipedia says: "It is a tour de force of pederastic fantasy and one of the frankest and most explicit texts on the subject to have been written before the twentieth century. It has been called "the first homosexual novel". [3]

Review

By Edmund Marlowe [4]

First published in 1651 and meant at one level as a lively carnival booklet, this is, both at heart and on the surface, a well-reasoned polemic in favour of pederasty. The eponymous Athenian boy is presumably intended to be the famous Athenian general well-known for the amorous attentions he excited in his boyhood, but the book is a philosophical dialogue rather than a story about real people: Alcibiades's schoolmaster Philotimes is dying to consummate his love for his pupil and has to overcome with reason the full array of early modern arguments against sodomy raised by the initially reluctant boy, until the latter is finally eager to accept him.

There was a profound contradiction over pederasty in early modern Italy. On one hand, the authorities followed the church in denouncing and fiercely persecuting all sodomy. On the other hand, recent research such as Rocke's statistical study of Florentine court records in his Forbidden Friendships has proven the reports of contemporary writers that most men were involved with boys, and reinforced their implication that attraction to both women and boys was taken for granted (whether or not acted on).

Rocco was the most important of a tiny number of writers who dared counter the various arguments of God, law and nature which were supposed to justify this persecution. Those of God and the law are shown to be irrational inventions and nature is shown to favour the love of men and boys and its consummation. Rocco, or rather Philotimes, then proceeds to show how both these things are superior to the alternatives.

Lest it be supposed to be a sombre treatise, the fun should be explained too. Mostly, I think it comes from the sheer joie de vivre underlying the dialogue. There is plenty of satire ranging from the unphilosophical over-excitement of the supposed philosopher to the outrageous excess of some of his arguments. Also, the most serious arguments are so peppered with luscious descriptions of the boy's physical charms and frank sexual description as to be highly erotic. In this it offers a valuable lesson to modern writers on sexual matters whose dour vocabulary tends to be at odds with the joy which should be at the heart of their subject.

Considering all the old arguments against homosexuality have largely been abandoned in modern Europe, it is ironic that the only beneficiaries have been men loving men, described by Philotimes as "mere beasts" for their goatish tastes. Rocco's own book remains nearly as forbidden as ever, this the only English translation published having become virtually unobtainable within a few years and the form of love it upholds newly persecuted with an intensity the mediaeval inquisition could only have dreamed of managing. Today a new Rocco is badly needed, for despite doing his best to answer all, Philotimes was unable to anticipate a day when the adolescent consent to sex he fought so hard and well to obtain would be held in contempt. Nor could he foresee the perversity of an age which would see the sexual abuse of boys, which he fiercely denounced himself, as a justification for terrorising men and boys genuinely in love.

An excellent "Afterword" shedding light on the book by D. H. Mader overstates an important point: he claims it is early evidence of the modern homosexual identity explained by Foucault as having emerged in the late 19th century. Dialogues devoted to explaining why loving boys is better than loving women go back to antiquity, and are surely far removed from claiming an identity based on an immutable orientation. Philotimes explains his preference for boys as based on reason and experience; his arguments would have had to be quite different if he thought he had no choice about it. [5]

See also

References

Media-BoyWiki

has media related to

Alcibiades