(Boylove Documentary Sourcebook) - The Encounter of André Gide with Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas in Algeria

From "Oscar Wilde: Love in a Dark Time", in Love in a Dark Time: And Other Explorations of Gay Lives and Literature by Colm Tóibín (New York: Scribner, 2004), originally published in 2001 in Australia by Pan Macmillan.

The first two months of 1895 were busy for Oscar Wilde. In late January he was in Algiers with Alfred Douglas. He wrote to Robert Ross: ‘There is a great deal of beauty here. The Kabyle boys are quite lovely. At first we had some difficulty procuring a proper civilized guide. But now it is all right and Bosie and I have taken to haschish [sic]: it is quite exquisite: three puffs of smoke and then peace and love.’ On Sunday, 27 January, André Gide, also in Algiers, was, according to his own account of this, checking out of the Grand Hotel d’Orient when he saw the names Oscar Wilde and Alfred Douglas on the slate in which guests’ names were written. Their names were at the bottom, which meant that they must have just arrived. His was at the top, in one of his versions of the story; it was beside Wilde’s in another. In any case, he later wrote that he took the sponge and wiped his name out and he made his way quickly to the station.

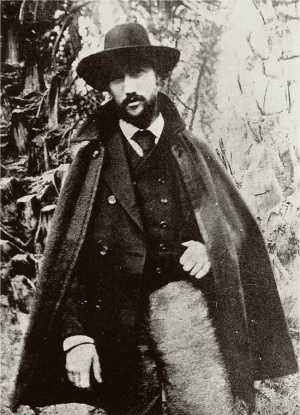

Gide, who was twenty-five, had met Wilde before in Paris and Florence. He left three accounts of their meeting in Algiers; some of these were later hotly denied by Alfred Douglas. The first, written the next day, was to his mother. He explained to her that he had, after much consideration the previous day, decided to return to the hotel and miss his train, as he did not want Wilde to think he was avoiding him. ‘This terrible man,’ he wrote,

the most dangerous product of modern civilization—still, as in Florence, accompanied by the young Lord Douglas, the two of them put on the Index in both London and Paris and, were one not so far away, the most compromising companions in the world.

Wilde, he wrote, was

charming, at the same time; unimaginable, and, above all, a very great personality. I was very lucky to have seen so much of him and to have known him so well in Paris a few years ago; that was his prime, and he will never be as good again . . . It’s impossible to gauge what is the young Lord’s intrinsic worth; Wilde seems to have corrupted him to the very marrow of his bones.

Two days later, Gide wrote once more to his mother:

One sees characters like this in a Shakespeare play. And Wilde! Wilde!! What more tragic life is there than his! If only he were more careful—if he were capable of being careful—he would be a genius, a great genius. But as he says himself, and knows: ‘I have put my genius into my life; I have only put my talent into my works. I know it and that is the great tragedy of my life.’ That is why those who have known him well will always have that shudder of terror when he is around, as I always do . . . I am happy to have met him in such a distant place, though even Algiers isn’t far enough away for me to be able to face him without a certain fear; I told him so to his face . . . If Wilde’s plays in London didn’t run for three hundred performances, and if the Prince of Wales didn’t attend his first nights, he would be in prison and Lord Douglas as well.

André Gide did not tell his mother what really happened to him in Algiers. He recounted it in Si le grain ne muert, written twenty-five years later, and he said that it was the turning point in his life. Wilde took Gide to a café in a remote part of the city. Alfred Douglas having gone to Biskra in search of a boy called Ali. As tea was being prepared for them, Gide noticed ‘a marvelous youth’ at the half-opened door. ‘He remained there quite a while, one raised elbow propped up against the door-jamb, outlined against the blackness of the night.’ When Wilde called him over, he sat down and began to play a reed flute. Wilde told Gide that he was Bosie’s boy.

He had an olive complexion; I admired the way his fingers held his flute, the slimness of his boyish figure, the slenderness of the bare legs that protruded from his billowing white shorts, one of the legs folding back and resting on the other knee.

As they left the café, Wilde asked Gide if he wanted the boy. Gide nervously said that he did. Wilde, having made the arrangements, laughed uproariously as his suspicions about Gide’s sexuality were confirmed. They both had a drink in a hotel and then made their way to a building where Wilde had a key to an apartment. The flute-player arrived, as did another musician for Wilde.

Gide held in his

bare arms that perfect, wild little body, so dark, so ardent, so lascivious . . . After Mohammed had left me, I remained for a long time in a state of quivering jubilation and, although I had already achieved sensual delight five times while with him, I rekindled my ecstasy a number of times after he had gone and, back in my hotel room, prolonged its echoes until morning . . . Since then, whenever I have sought pleasure, it is the memory of that night I have pursued.

Nothing again, it seems, was ever so much fun for Gide. He subsequently met up with Douglas, who had Ali in tow, dressed like Aladdin, and aged, Gide told his mother, twelve or thirteen. All three stayed in the Hotel Royal in Biskra. In his conversations with Gide, Douglas ‘returned incessantly, and with disgusting obstinacy to things I spoke of only with the greatest embarrassment—an embarrassment that was increased by his total lack of it.’ And yet Gide wrote that he found Douglas ‘absolutely charming’.

Wilde left Algeria on 31 January 1895 to attend rehearsals of The Importance of Being Earnest, which opened on 14 February. The incoming ferry was twenty hours late because of a storm, and the crossing of the Mediterranean was rough. He stopped in Paris on his way to London and saw Degas, who repeated to him a comment he had made on the opening of a Liberty’s shop in Paris: ‘So much taste will lead to prison.’