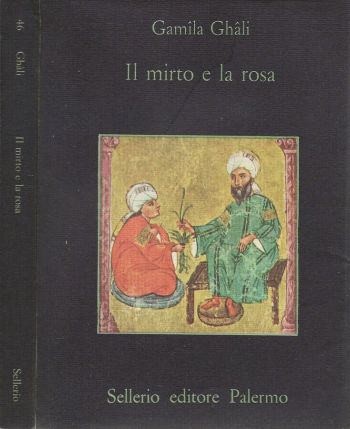

A review of The Myrtle and the Rose by Annie Messina

|

News

from Greek Love Through the Ages  The Myrtle and the Rose is a magnificent, beautifully-written love story to die for. It is often compared to The Thousand Nights and One Night for the obvious reasons that both are highly readable romantic adventure stories set in the world of mediaeval Islam, and written in a similarly simple and lucid style. The Myrtle and the Rose is not fantastic or fabulous in the sense of having djinn or magic carpets, but it has something of these qualities through being an extraordinarily beautiful and emotionally compelling story of ideal love, which stays in the mind long after one has forgotten the details of Shahrazade’s entertainment. Handsome and high-minded Prince Hamid al-Ghazi, the 42-year-old ruler of a principality on the edge of the Abbasid caliphate around the year 1000, impulsively visits a slave merchant from whom he had recently acquired a beautiful girl who had quickly risen to become his favourite concubine. The merchant is appalled by his lost opportunity because the only valuable slaves he has in stock are six pretty Greek boys of eight or nine and he knows the prince has never shown any interest in boys. Fortuitously, Hamid is distracted by unseemly yells coming from another slave-boy’s violent resistance to imminent castration and orders the suspension of the operation until he has been told the story behind it. It transpires that the boy, an astonishingly beautiful twelve-year-old of noble birth and exquisite breeding, had been treacherously kidnapped into slavery, and had so persistently and courageously resisted his fate that his present owner was resorting to castration as the only practical means of breaking his spirit. The moved prince demands to see the exhausted boy, who opens his eyes, gazes at him, knows at once he has met a kindred spirit who will help him and tells him to take him away with him. Hamid does just that, thus inaugurating a deeply moving love affair in which both the man and the boy, soon renamed Falcon as he cannot remember his past, feel totally bound to one another. “One look was enough for anyone to sense the strength of the feeling that bound them together.” Annie Messina  The author was the daughter of the Italian consul general in Egypt, where she spent most of her life and worked as a translator. She undertook exhaustive research for her story, which is thus most definitely not a European fantasy (suspicion of being which was presumably the reason for her choice of an Arabic pen name). The result is a fascinatingly convincing portrait of Greek love as commonly practised in the Moslem world for over a thousand years. It is taken for granted that any normal man will be capable of attraction to both women and boys, though preferences vary. Hamid’s harem, “numerous but carefully chosen, was sufficient to satisfy his robust virility,” and he has apparently never fallen for a boy before he sees Falcon. Nevertheless, from the moment he does, there is no question about his absolute devotion or that it outshines his passion for his concubines: “never before had he felt such passionate tenderness, not even when he held a beloved woman in his arms.” Nor is there any doubt that his love for the boy is erotically inspired and therefore Greek. That is made clear from the outset. The first night Hamid has brought the sick and severely weakened child to his palace, Hakim, the old doctor who has been like a father to him, warns him against putting the boy in his own bed, and they have the following exchange about it:

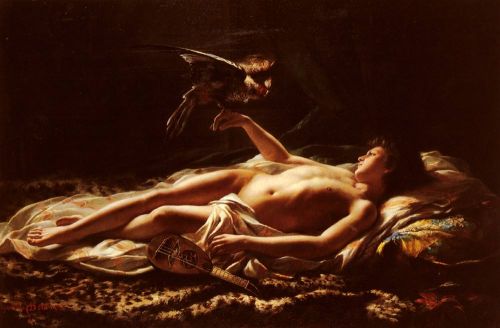

However, part of Hamid’s high-mindedness is to be a good Moslem and liwat (pedication) is therefore forbidden for him by Allah, whom he believes sent Falcon to him in the first place. So, he and his beloved sleep in one another’s arms and they eagerly caress, there is not the slightest secrecy about this or about their mutual love and Hamid’s appreciation of Falcon’s beauty, but they never quite have sex. At the very end of the story, Hamid acknowledges to himself that the body he really longed for was not that of his favourite concubine, but that “of the boy lying beside him, the body he had desired from the beginning but had always respected because of a mysterious inhibition.” He nearly then succumbs to the terrible temptation and makes the moves towards what is clearly going to be liwat (thankfully no concessions here to some modern nonsensical claims that anything else was the longed-for sexual act between man and boy in more natural epochs), but, at the last moment, he conquers the “demon inside me.” Nude Male with Falcon by Germain Detanger, 1882 Hamid’s love for Falcon thus represents a Moslem ideal, real enough for the high-minded, but not something many or probably even most men lived up to. To most people, “it was obvious he loved the boy as a man loves a woman, ” and we are left in little doubt as to what most men would like to do with, or rather in, Falcon. Messina’s portrait of Islamic pederasty is rounded off with Hamid’s bitter enemy and opposite in character, the emir Husain ibn Ali, an amusingly larger-than-life but still credible villain. In stark contrast to Hamid, for whom Falcon is the exception in an otherwise heterosexual like, Husain is exclusively inclined “toward boys between the ages of eight and fifteen,” and has copious sex with them without affection or even good will. The sex is so sadistic that they somehow soon die. His motives or the source of his excitement owe more to hate than love, as set out in this little lecture delivered to a disgusted Hamid during a social visit:

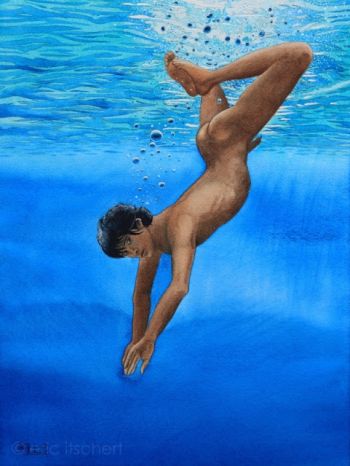

Thus Husain, like his opposite, incidently illustrates the pre-modern reality that the choice for men between women and boys was one of taste formed by experience rather than immutable and involuntary orientation. Considering both The Myrtle and Messina’s other novel, La palma di Rusafa, focus with extraordinary insight and understanding on Greek love in a very masculine culture, it is surely striking that she was a woman and, as it happens, that most of the best novels depicting Greek love have been by women. The most outstanding case is of course the very best, Mary Renault, but many others come to mind: Isabelle Holland, Ursula Zilinsky, Frances Vernon, Laura Argiri, Marguerite Yourcenar, Bron Nicholls and apparently Chris Hunt. The latter case highlights the anomaly here, as she is said to have adopted a male pen name to avoid putting off a largely male readership who might be sceptical that a woman could understand male homosexual feeling.  Why is this? A wise woman told me it was because a woman can more easily empathise with the boy in a Greek love affair, knowing what it is like to love and be loved by a man. I find that convincing, but one must remember that Renault and Yourcenar at least were lesbians. A key here is probably that though Renault was an independent-minded woman who was personally repelled by taking the conventional role society then expected of her sex, she was no male-hating feminist of the variety that has done incalculable damage to humanity in the last two generations. Socially, she preferred the company of men and she chose to write about ancient Greece because she was drawn to its masculine values. Little seems to be known about the also unmarried Messina, but there are interesting comparisons to be drawn between her writings and Renault’s. An engaging and perhaps related question is why Greek love is often depicted in the historical sources for many old civilisations and the writings of historically-accurate novelists like Messina and Renault as emotionally more powerful and nobler than heterosexuality? This was pretty much a general assumption in classical Greece, most influentially appearing in Plato’s dialogues the Symposium and the Phaidros, where it was simply assumed as a matter of course that the object of serious and worthy love must be a boy, and the idea echoed around the globe until a couple of centuries ago, especially in Moslem lands. The conventional modern answer going back to Engels and heavily promoted by feminists is that women in the places where Greek love was idealised were so oppressed and deprived of the opportunity to flourish intellectually that they had no fair chance of competing with boys for men’s esteem. Quite apart from the absurdity of depicting a status quo that prevailed almost everywhere for almost the whole of recorded history as oppressive of half of humanity rather than being the natural outcome of what was found to be most in harmony with human nature, there is in practice little evidence that people felt this way. Consider Hamid. He genuinely loves his concubines, to one or more of whom he makes love every day at home and proud of his ability to do so well, so that they long for his visits. Lailah is his favourite, but he feels it incumbent on him to ensure the others do not feel neglected. Lailah herself pines for him when he is away and is fiercely loyal to him – there is not the slightest hint she feels “oppressed”. Falcon, whom Hamid first encounters on a shopping trip to buy presents for his women, is equally courteous. When finally introduced to the women, he “behaved with his usual gentility. He thanked Lailah for the joy she gave his master.” The notion that boys could attract men more easily than women because they had received a better education also loses sight of the fact that Falcon was only twelve when Hamid fell in love with him and other men fell in love with boys even younger. The list of Falcon’s physical attributes and qualities of character that draw Hamid to him is long indeed, but high education, knowledge and intellectual accomplishment are certainly not among them. “Your beauty is the only wealth you possess,” Hamid tells him frankly at the outset. Clearly the explanation for the appeal of boys to men must be sought elsewhere. In this review of what is a novel rather than a treatise, I can only draw attention to the some of the insights it offers. Diving Boy by Eric Itschert  “Though [Falcon]’s limbs still retained the softness of childhood everything about him predicted the future harmony of a perfect virility.” And for Hamid, witnessing and helping Falcon towards that virility was always to be a source of pride and happiness. When it transpires that Falcon can ride well, Hamid is “delighted at the new prowess he had discovered in his child.” Hamid is similarly thrilled when the boy shows himself good at archery and spectacularly so at diving and swimming and eager to please him through this, as it shows how powerfully he is managing to inspire him. By contrast, Hamid’s women would seem to have come to him fully formed; he does not teach them anything except perhaps love-making, so does not have the satisfaction of causing them to blossom. Falcon first appealed to Hamid to take him away “in the name of their common nature.” I think what is specifically meant here is their shared nobility of character, but is it not more broadly the case that their shared maleness, being complementary (ie. one a boy and the other a man), increased their mutual appeal? Hamid is the myrtle of the title (representing manliness) and Falcon the rose (representing the innocence of childhood), and the latter hero-worships the former as only a boy can. “The boy’s faith in his omnipotence and invincibility was too sweet to lose.” A journey they undertake together through Hamid’s realm “completed the bond between them,” as it “gave Falcon a clearer view of his master’s world – a man’s world.” Hamid’s women can never belong to a man’s world or develop into the beings they should be through emulating their lord. Falcon had lost his home and had nothing a boy needs. Hakim early on guesses “he’s been brought up without love. He’s starved for love, but he wants it only from you, Sire.” Falcon knows instinctively he can trust Hamid to love, protect and nurture him and it is hard to see how anything could be more beneficial than that to one in his circumstances. It is showing himself worthy of that total and unconditional trust that is henceforth the greatest source of Hamid’s pride and happiness. When he has finally come close to abandoning self-restraint and taking Falcon sexually, he feels a greater despair than he has ever known because he thinks “the trust and love of his boy were forever lost.” Happily, he is wrong and it is on the following note of restored equanimity and mutual trust that man and boy undertake the deed that brings this splendid tale to its woeful albeit uplifting end. |