Guy Strait

Guy Strait (March 25, 1920 - March 25, 1987), founded the first gay newspaper in San Francisco in 1961. By 1977, he had "cornered the market on the production of 'kiddie porn'".

It is belittling to dismiss Guy Strait as a child pornographer, or excuse him as a pornographer who strayed over the bounds into children, or explain him as a product of the San Francisco sixties counterculture. In some ways that counterculture was a product of Guy Strait. He published the city’s first gay newspapers in 1961. He defined that time and place: his 1967 essay “What is a Hippie?” is on college reading lists today.

Early Life

Guy Strait was born in Texas in 1920, the tenth of eleven children. At the age of 18 he traveled across the Yucatan Peninsula photographing the unclad natives and passing out Bibles; in World War II he served in the Army; and in the early 1950's studied fine art at the Chicago Art Institute. He had a photography studio in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district in the 1960's. [1]

Appearance

The Illinois prosecutor who send Strait to jail said he "appears to be an intelligent, kind and affable cherub." The author Clifford L. Linedecker, who interviewed Strait in prison, describes him as having "a barrel body, thinning white hair that sticks straight out from his hair in clumps, a hearing aid, and reading glasses that slide down his nose disclosing watery blue eyes. He looked every bit a mischievous old troll." Strait himself, after warning readers of a young imposter, whom he described, then described himself, "The Editor is not at all like that and is: 5'5", wt 165, red eyes, greying hair, about 100, and with very little accent. In fact he looks exactly like a retired vice cop." [3]

San Francisco Gay Rights Pioneer

In 1961 he organized a gay rights group, The League for Civil Education (LCE), and began to publish newspapers and magazines.

"In 1961, Guy Strait began publishing the first gay newspapers in San Francisco — the League for Civic Education News, the Citizen News, and Cruise News and World Report — from his offices on Minna Alley. These newspapers were available by subscription, but were also distributed free in gay bars and were sold openly at newsstands. These publications fostered a greater sense of gay visibility and laid the groundwork for gay political mobilization later in the decade." [4] Another source confirms that he "sought to politically organize gay bar patrons by distributing the paper for free." [5] One historian calls him a "bar-based activist". [6] Other Strait publications include a 1963 guide called The Lavender Baedeker and in 1967 the Haight-Ashbury Free Press and the Bar Rag. He signed some editorials as "the DOM", short for "Dirty Old Man".

Strait himself later unpretentiously described Cruise News as "earthy" and "muckraking" and said it was not very profitable.[1]

Mr. Strait's interest and publications were not confined to politics, however. "Through his political publications, Guy Strait advertised his photographic enterprise as well as his political views. He eventually renamed the paper Cruise News and World Report and devoted most of the back page to a section titled "Models Galore for Sketch Artists, Sculptors, and Others." Readers could order 8x10 photos of two dozen young men, all between the ages of 15 and 23." [7]

Guy Strait, Pornographer

Strait later said he got into the pornography business when he was offered $2,000 each to lay out two magazines. The money was easy, the competition was low quality, and he already had "thousands of negatives". Robin Lloyd claims Strait was responsible for the "first of the commercial chicken magazines, Hombre, Chico, and Naked Boyhood were among the titles." [8]

Strait told a Senate subcommittee that he wouldn't photograph children under fourteen for pornography. "Over fourteen, I don't consider them children. They're sexually mature. Let's say fourteen is not a child, thirteen may or may not be, and fifteen sure as hell is not." He claimed to have no trouble finding models. "No one jumps in front of a camera for money. These kids do it for ego. Take a youngster who has never been appreciated. You tell him he's good looking enough to be in front of a camera and people will want to see him and be interested."[9] According to the Illinois Legislative Investigating Committee, he claims never to have filmed children in sexual activity with adults. [10]

"It was not illegal at the time, sir."

While accusations involving pornographic films were bandied about in the press in the 1973 scandal, none of the 90 indictments were for pornography, and Strait was sent to prison not for filming three Rockford boys, but for taking one of them to bed afterwards. Strait faced down Senator Malcolm Wallop of Wyoming on legality when called before a Senate investigative subcommittee in May, 1977:

Senator WALLOP. Did you know what you were doing was illegal?

Mr. STRAIT. The Supreme Court didn't say so.

Senator WALLOP. Well, somebody has.

Mr. STRAIT. I am not here in Illinois as a result of any filming, on the record. And if I were to offer my brief to the three Senators and if they found me guilty, I would withdraw my appeal.

Senator WALLOP. But with regard to the activities of filming and making these loops, did you know that that was illegal?

Mr. STRAIT. It was not illegal at the time, sir.

Senator WALLOP. So it was legal?

Mr. STRAIT. Sir?

Senator WALLOP. You are claiming that it was legal?

Mr. STRAIT. At the time, yes.

Senator WALLOP. And there were minors involved?

Mr. STRAIT. Yes.

Oh, I see what you are saying. The State law rather than the Federal.

Senator WALLOP. State or Federal?

Mr. STRAIT. No, at that time it was legal, that was before Mr. Burger's court made its decision. You will have to remember, gentlemen, that I haven't had anything to do with the pornographic business involved for 4 years.[9]

Los Angeles and Lyric

An on-line source claims Guy Strait moved to Los Angeles in 1970 and lived in a house on Roderick Place, a dead-end street next to the Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale. [11] Linedecker says he lived in the Hollywood Hills and maintained a house trailer for editing film in Redwood City, south of San Francisco. When he was arrested in the 1973 Lyric scandal his address was given as 7718 Skyhill Drive, Studio City. [12]

In Los Angeles he formed a distribution company, DOM-Lyric, in partnership with Lyric International. Lyric, whose most ambitious work was the full-length mainstream film The Genesis Children, featuring Peter Glawson and other young actors. Lyric produced only "physique" photography, never pornography,[13] but apparently found Strait's distribution network useful.

Scandal, flight and prison

Strait was arrested in the fall of 1973, in the scandal that brought down Lyric and which the Meese Commission later called "the first child pornography ring [...] brought to public view." [14]

Strait and an associate were arrested before the others twelve accused in the scandal. Samples of Strait's work had turned up when a "sex ring" was broken up in Houston, and an unedited film was found by police in the Redwood City trailer. Strait says the film showed three boys and a girl, while Sgt. Lloyd Martin of the LAPD (who seems to be fixated on boys) mentions only the three boys. But apparently the Holiday Inn mirror reflected Strait with a 16mm camera on his shoulder.

Strait says he jumped bail and the charges were later dropped. Linedecker says he "became something of a cause célèbre for a time." Robin Lloyd quotes one of Strait's magazines as saying he was in Turkey or Greece but that police thought he was in New York.

He appears to have rather been bouncing in and out of prison. Court and newspaper records provide a rough chronology. Strait made a pornographic movie with minors in Rockford, Illinois, on March 1-2, 1972; was arrested in the Lyric scandal around Labor Day of 1973; and was serving time in Springfield, Missouri in December of 1975 after a conviction on Federal charges.[15] He must have been released, as he was arrested in Phoenix, Arizona on April 23 of 1976, and extradited to Illinois on the Rockford charges.

Rockford case

The Rockford, Illinois case in which Strait was arrested and convicted is described in contemporary newspaper accounts and court papers, and was based on events in March, 1972, a year and a half prior to the Lyric scandal, though arrests were only made in 1976, and UPI reported:

Police Investigation Continues In Rockford Homosexual Case

ROCKFORD (UPI) - Authorities have accused four men, including a mental health caseworker, a newspaperman and a "Porno King," of joining in a homosexual group which lured teen-age boys into involvement. Several other men are under suspicion. The four were arrested and charged in recent weeks as part of a 10-month investigation, Robert Gemignani, first assistant state's attorney for Winnebago County, said Tuesday. Gemignani said the four men invited at least five to seven boys ranging in age from 12 to 15 to parties and gave them beer and marijuana to lure them into homosexual acts. "Participation by boys at that age can be induced by seduction," he said. None of the boys went to authorities, but they complained of the incidents when they were interviewed, Gemignani said. He identified those charged [...] and Guy Strait, who is wanted on about 19 counts of morals violations in San Francisco. [...] Strait, described by authorities as an international "Porno King" who deals in films of young boys engaging in homosexual acts, was still at large Tuesday.[16]

An appeals court ruling overturning Strait's conviction on statue of limitation grounds described a more limited case:[17]

On May 13, 1976, Guy Strait (hereinafter "defendant") was charged with the March 3, 1972 offense of indecent liberties with a child. […]

The facts surrounding the above offense are that the defendant came to the Holiday Inn in Rockford, Illinois, in March of 1972, to shoot a pornographic movie. (Victim) was one of three participants, and during the movie sessions he engaged in various homosexual activities with two other young males over a two-day period. (Victim), who was 14 years old at the time, received $150 for his role in the movie. (Victim) testified that this was the last film he ever made.

On the night of March 3, 1972, (Victim) returned to the Holiday Inn at defendant's invitation for a dinner engagement. However, the two went straight to the defendant's bedroom where the defendant asked (Victim) if he would mind "going to bed with him." (Victim) testified that he did not question the defendant as to what he meant by "going to bed." (Victim) testified that the defendant then performed anal intercourse on him. Afterwards, the defendant apologized for not taking (Victim) to dinner and gave (Victim) $5 or $10 and told him to go home and get something to eat. (Victim) testified that he turned the defendant down on his request for (Victim) to "go down on him." It is the defendant's activities on the evening of March 3, 1972, for which the information was returned.

The appeals court further noted:

Because the charging information is so deficient as to require reversal, we need not reach defendant's declarations against the morality of the complainant and whether or not this 14-year-old boy is a prostitute. These assertions made by an admitted producer of child pornography present grave doubt in this court's mind as to the capacity of the defendant to judge the morality of anything above the level of a crawling object.

The contempt and revulsion elicited by a detailed reading of this record cannot operate to deprive the defendant of his right to be tried according to established legal standards. He was not so tried, and we accordingly reverse the judgment of the circuit court of Winnebago County.

The appeals court decision names the victim, who as of 2016 was living in Florida. The Illinois Supreme Court upheld the reversal on Oct 6, 1978.[18]

Following reversal, another indictment was returned charging defendant with the same offense based on the same conduct as that in the first prosecution. This indictment alleged certain limitation-tolling facts.

Defendant moved to dismiss the charge on due process and double jeopardy grounds, claiming that reprosecution was barred because he never received appellate review of the sufficiency of the evidence in the first trial. (See People v. Taylor (1979), 76 Ill.2d 289, 391 N.E.2d 366.) He did not, however, reassert his claim that he was not proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt in the original prosecution of the cause. In denying the motion, the trial court noted the reversal was obtained because of a defective information. Thus, the court determined that the case should be treated the same as a retrial following a reversal for trial errors not based on the sufficiency of the evidence. (See United States v. Ball (1896), 163 U.S. 662, 41 L.Ed. 300, 16 S.Ct. 1192.) The court accordingly held that reprosecution did not violate double jeopardy principles.

Defendant subsequently entered a negotiated plea of guilty to the renewed charge. After the factual basis of the charge was recited, and defendant was admonished, the trial court accepted the guilty plea and sentenced defendant to 8 1/2 years of imprisonment pursuant to the plea agreement. No motion to withdraw the plea was filed, nor was a direct appeal taken pursuant to Supreme Court Rules 604(d) and 605(b) (87 Ill.2d R. 604(d) and 605(b)).[19]

Ostracism and death

Strait was released from prison in Illinois in 1980, just after his sixtieth birthday. While online rumor claims he left the country and died in exile in Europe, he seems to have lived and died humbly in San Francisco. The Polk's Directory for San Francisco for 1981 has a Guy Strait at 349b 10th St, repeated in the 1982 edition, but not in the 1980 edition.[20] It is a neighborhood of two-story buildings, and Polk's shows Strait's neighbors included an auto-body shop, muffler shop, crankshaft grinder, plumber and similar services.[21].

Strait had been shunned by the organized gay community long before his arrest. The exit of cofounder José Sarria and others from LCE was a revolt against Strait's autocratic style.[15] A 1966 letter from a director of gay rights organization ONE, Inc, refers disdainfully to "... those whose primary interest is 'fun for the homosexual'. Possibly there should be included also one more division, the people who are out to make a buck for themselves. For such reasons I find it very difficult to place Tavern Guild, Guy Strait, physique publication editors and some others as being part of the Homophile Movement".[22]Another letter, this to ONE organizer Bois Burk, observes that while there’s room for plenty of organizations, "those which perform no real service, or are improperly conducted will fade away, even as it now appears Guy Strait may be doing."[23]

The disparagement of Strait wasn't confined to private letters, but also appeared in ONE's newsletter.

Evidently undisturbed by scruples of this sort, Guy Strait, San Francisco publisher of a number of irresponsible and often completely untruthful scandal sheets, used three votes whenever it pleased him to do so, despite his having published a statement that he is not an organization, and that his interest is in making money. Some of the delegates wondered why he should have been allowed on the premises at all. At one point, rising from his seat he stated that he had often been called a "dirty old man" and may have mistaken the laughter from delegates as being in disagreement instead of as applause for the so candid self-revelation.[24]

The name-calling was reciprocated, with one edition of Citizen News leading with, "THE HOMOSEXUAL VIEWPOINT FROM ONE MAGAZINE, OR HOW PHONY CAN YOU GET! Written By Guy Strait, Editor of the CN", reproducing and criticizing a ONE editorial.[25]

This anecdote told in the 1980s by fellow gay rights crusader José Sarria, with whom Strait had founded LCE, dissidents from which founded SIR - Society for Individual Rights, suggests that the years had not soothed passions, and both shared nonpersonhood:

"Guy Strait is still alive. He went to prison and spent quite a bit of time in there. He was arrested for pornography along with an heir to a large American company who was able to get out of the country and live in North Africa, while Guy wasn't able to. He stayed here and took the brunt of it. He was finally let out of prison in Illinois.

"SIR collapsed after seventeen years, but there was a celebration of the twentieth anniversary of its founding a few years back. Invitations were sent out inviting people to come and celebrate the years of SIR. I went. Guy Strait went. A lot of early, early people that belonged to the League for Civil Education and later joined SIR went. People were honored. The president was honored, and this and that and the other thing—and they very nicely ignored Guy Strait and myself. That's the way the whole evening went; we were very nicely ignored. SIR appeared. They didn't say how SIR came to pass. SIR appeared because the League appeared first I guess Jesus made the league and three days later SIR appeared. I guess SIR just fell out of the sky!".[26]

As to his death,

"Guy Strait, a gay movement pioneer with a love of the beauty of early and pre-teen boys and the ability to capture that beauty on film, died on March 25, 1987 - 67 years from the day he was born in Dallas, Texas. He died from a heart attack at the Laguna Honda Home in San Francisco, where he had been placed ten days earlier following a serious stroke."[27]

Size of the market

Strait "was one of the nation's leading pornographers ... he had cornered the market on the production of ‘kiddie porn'," according to the Chicago Tribune. [28]

Strait's actual volume of business is hard to be sure of. The Chicago Tribune ascribes to "police" an estimate that he made $5 to $7 million in his career (id.). The high figure would average to just under $300,000 per year over his twenty year career. Linedecker's numbers are the unsupported figures of Lloyd, who claims DOM-Lyric put out ninety magazines with a wholesale price of $2.50, retail of $5.00, and initial print runs of 10,000, making a quarter million dollar gross. The print run is based on "distribution lists taken in police raids". Linedecker says the Illinois prosecutor told congressmen that Strait's distribution list had at one time 50,000 customers, but that Strait says there were 942 names. Strait's films were mail-order only, so the size of the distribution list is the upper limit for sales.

These numbers are skimpy, unverifiable, and inconsistent. Making sense of them is beyond the scope of this article. It seems clear however that if Guy Strait, the man with a "corner on the market" was averaging less than $300,000 a year total from many kinds of pornography, of which child porn was only a part, it's just not possible that child pornography was a multi-million dollar business in the 1970's.

The boy who killed himself

One of the few online sources on Strait mentions "the boy who killed himself in the affair involving the arrest of the photographer Guy Strait."[29] According to the Chicago Tribune, Strait's "... only regret is the three boys testified against him. 'Their lives were ruined because they went to trial. One boy eventually committed suicide.'" [28] While Strait attributes the suicide to testifying, various authors who mention him seem to take that attitude that if the boy had to testify the blame was all Strait's. However, the "affair" was not the scandal that brought down Lyric, and the boy was not one of the Lyric boys seen around the pool with the cinderblock walls at the Lyric studio.

Guy Strait and J. Edgar Hoover

Anthony Summers cites a Charles Krebs as relating that two boys from the Lyric studio were driven down to Hoover in San Diego, "I think the arrangements were made by one of Billy [Byars]'s friends, an older man." Krebs claims to have gone along on the trips a couple of times. Summers quotes detective Don Smith of the Los Angeles police as confirming that, "The kids brought up several famous names, including those of Hoover and his sidekick."[30] Strait was the oldest of those arrested in the 1973 scandal. Linedecker says Strait "claims to be the first person to accuse the respected law enforcement leader of being a closet queen." (Linedecker, p. 229) Strait may have been the unidentified "older associate"; Summers doesn't give the name although he and others clearly knew it.

Further Information

There is an excellent chapter on Guy Strait in the 1981 Children in Chains by Clifford L. Linedecker.[1] Linedecker, who has written a number of "true crime" popular books, mostly lets Strait have his say, as he explains on page 228: "This account is based on his version of his life and activities except where another source is specifically quoted or credited." Linedecker also corrects some of the wilder errors made by Robin Lloyd when discussing Strait in his highly unreliable 1976 book For Money or Love, which triggered the 1977 kiddie porn panic.[31] He includes information on the models of cameras Strait used; the costs and raw-to-finished ratios of twelve-minute film loops; and means of avoiding piracy, such as lowering the quality of 8mm product and salting the mailing list with rabidly anti-porn clergy. Linedecker closes with Strait's future plans, "publishing and distributing three books he had already written. One is Memoirs of a Dirty Old Man". Except where noted this account follows Linedecker, whose book is recommended to anyone with a deeper interest in Mr. Strait.

The report of the Illinois committee is also recommended; the committee actually did quite a bit of investigation. It deflates a lot of the wild numbers bandied about in the press, and exposes some of the McCarthyesque assertions of the anti-porn crusaders.

The Chicago Tribune articles are reprinted in Sexual Exploitation of Children, Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Crime of the House Comm. on the Judiciary, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. (1977) pp 428-42, and also in PROTECTION OF CHILDREN AGAINST SEXUAL EXPLOITATION Hearings before the Senate Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency, 95th Congress, 1st Session, Chicago, Ill., May 27, 1977, Washington, DC. June 16, 1977, pp. 130-158, as well as in the report of the Illinois committee.

The Chicago Tribune printed a photo of Guy Strait on May 17, 1977, p. 8. It is not included in any of the three legislative reports.

The ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California, has among its holdings the Erotic and physique studios photography collection circa 1930-2005. The catalog finding aid lists "Box 9-10 DOM (San Francisco, California)1961-1976 Physical Description: 641 photographic print." and includes a list of models depicted, and a historical note that appears to have been lifted from this wiki. In the same collection is "Box 21 Lyric Studio (San Francisco, California) undated Physical Description: 84 photographic prints."

There is a file for Guy Strait among the 341 boxes of the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives ONE Subject Files Collection which "... consist of more than 8,100 unique files of businesses, organizations, people, and topics [...] The bulk of the documents are newspaper and magazine clippings along with promotional materials such as advertising fliers, brochures, and mailers for businesses, organizations, and events."

There in a videotape of a December 1, 1989 interview with Guy Strait as part of the ONE Archives but physically at the UCLA film school. The ONE catalog record has the annotation "(not found. mb. 9/1/10)" The UCLA Library has an entry for the ONE Institute & Archives, and that includes a link to the online inventory list, which says "Last update 12/12/2014" and includes an entry for "Guy Strait Interview, INV # M127724, One Institute Call No. - VV 0020."

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Linedecker, Clifford L. 1981. Children in chains. New York: Everest House. Chapter 14, "Chicken Hawk", focuses on Strait.

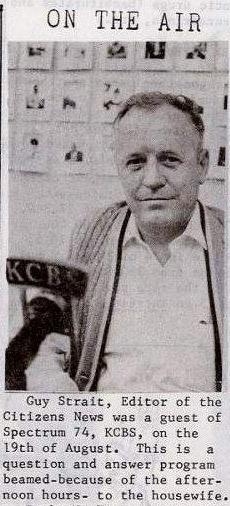

- ↑ "On The Air"Citizen News, Volume III, Number 22, page 14

- ↑ Strait, Guy. (1964, August 17). Imposter. Citizen News, Volume III, Number 21, page 11

- ↑ San Francisco’s Lower Market Street at GLBT Historical Society.

- ↑ Historic Context Statement Prepared by: Damon Scott for the Friends of 1800

- ↑ Boyd, N.A. (2003). Wide-Open Town: A History of Queer San Francisco to 1965. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Friedman, M. (2003). Strapped for cash: A history of American hustler culture. Los Angeles, Calif: Alyson. p. 138

- ↑ Lloyd, Robin. 1976. For money or love: boy prostitution in America. New York: Vanguard Press.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 PROTECTION OF CHILDREN AGAINST SEXUAL EXPLOITATION Hearings before the Senate Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency, 95th Congress, 1st Session, Chicago, Ill., May 27, 1977, Washington, DC. June 16, 1977, pp. 22-34

- ↑ Sexual Exploitation of Children, a report to the General Assembly. Illinois Legislative Investigating Committee. Chicago, Ill. August 1980. p. 167.

- ↑ History at Arnie's Place

- ↑ Pair Arraigned in Case Involving Homosexuals. The Van Nuys News. 7 September 1973, p. 8

- ↑ Campfire Video interview ¶ 3

- ↑ Attorney General's Commission on Pornography: final report. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Justice (1986) Chapter 11, p. 131)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Guy Strait Jailed!". Gay Crusader. San Francisco. Issue 24, December 1975, p. 3

- ↑ Police Investigation Continues In Rockford Homosexual Case. Freeport Journal-Standard. February 25, 1976. p. 9

- ↑ 52 Ill. App.3d 599 (1977) 367 N.E.2d 768

- ↑ 72 Ill.2d 503 (1978)

- ↑ 110 Ill. App.3d 514 (1982)

- ↑ Polks 1981 p 1217

- ↑ Polk's

- ↑ Conger, Dick. 24 March 1966. Letter to Warren D. Atkins. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives.

- ↑ Letter to Bois Burk, 9 February 1967. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives

- ↑ “What is a homophile organization?” ONE confidential, volume 11, number 9 (1966 September). Issued monthly. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives.

- ↑ Press regarding ONE, Inc. (1954/1969), ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives

- ↑ Gorman, M. R. (1998). The empress is a man: Stories from the life of José Sarria. New York: Haworth Press. p. 199

- ↑ Artist/activist fought for rights of men and boys

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "His Only Regret: I Got Caught". Chicago Tribune, 17 May 1977, p. 8., via Protection of Children Against Sexual Exploitation: Hearings Before the Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency of the Committee on the Judiciary of the United States Senate, p. 144.

- ↑ Sexual exploitation of children: a report to the Illinois General Assembly The original reference is no longer online. The IGA report, p. 167, says Strait "lamented the suicide of one of the boys, commenting that he killed himself because he had to go to trial."

- ↑ Summers, A. (1993). Official and confidential: The secret life of J. Edgar Hoover. New York: Putnam. pp. 377-378

- ↑ Lloyd, Robin. 1976. For Money or Love: Boy Prostitution in America. New York: Vanguard Press.