Pederasty in ancient Greece

| Part of the boylove history series |

|

| Portal:History |

Pederasty in ancient Greece was a publicly acknowledged practice from Archaic times until the end of Classical antiquity. It consisted in a relationship with mentoring and erotic components between an adolescent boy, called the eromenos ("beloved"; Greek: ἐρώμενος, pl. ἐρώμενοι, eromenoi), and an adult man outside of his immediate family, known as the erastes ("lover"; Greek: ἐραστής, pl. ἐρασταί, erastai), and was constructed as an aristocratic moral and educational institution. As such, it was seen by the Greeks as an essential element of their culture from the time of Homer onwards.[1]

The term "pederasty" (Greek: παιδεραστία, paiderastia) originates from the combination of the words pais ("boy") and erastēs ("lover"; cf. eros). In ancient Greek homoerotic poetry, the noun paiderastēs and the verb paiderastein were respectively replaced by paidophilēs and paidophilein (synonyms from which the modern term "pedophilia" is derived), in order to fit the elegiac metre favored for the genre.[2] In a wider sense, these words referred to erotic love between adolescent boys and adult men. The Greeks considered it normal for any man to be drawn to the beauty of a boy—just as much if not more than to that of a woman;[3] what they disagreed upon was how and whether to express that desire.

Pederasty is closely associated with the customs of athletic and artistic nudity in the gymnasia, delayed marriage for gentlemen, symposia and the seclusion of women.[4] It was also integral to Greek military training, and an important factor in the deployment of troops.

History

Possible beginnings

The ancient Greeks of the pederastic city-states were the first to describe, study, systematize, and establish pederasty as an institution. The origin of that tradition has been variously explained. One school of thought, articulated by Bernard Sergent, holds that the Greek pederastic model evolved from far older Indo-European rites of passage, which were grounded in a shamanic tradition with roots in the Neolithic.

Another explanation, articulated by Anglophone scholars such as William Percy, holds that pederasty was formalized in ancient Crete around 630 BC as a means of population control, together with a delayed age of marriage for men of thirty years.

The earliest Greek texts, specifically the works attributed to the Ionian poet Homer, do not overtly document formal pederastic practices. A number of theories attempt to explain that lack. A largely held view is the Dorian hypothesis, first established by K.O. Müller in the 1800s. According to this theory, pederasty was brought in by the Dorian warrior tribes who conquered Greece around 1200 BC. They settled most of the Peloponnese along with the islands Crete, Thera, and Rhodes. This forced the Ionian Greeks towards Asia Minor, but left important cities in Attica and Euboea. Another explanation is that the epic style excluded discussion of certain topics, among them pederastic relations. Nevertheless, Homer's works hint at homoerotic relationships obliquely, as in the mentions of the myth of Zeus and Ganymede in the Iliad, and the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite.

Alternative forms

Pederasty was constructed in various ways. In some areas, such as Boeotia, the man and boy were formally joined together and lived as a couple. In other areas, such as Elis, boys were persuaded by means of gifts, and in a few, such as Ionia,[5] pederastic relationships were forbidden altogether. The Spartans, however, were said to practice chaste pederasty.[6] Where allowed, a free man was usually entitled to fall in love with a boy, proclaim it publicly, and court him as long as the boy in question manifested the traits prerequisite to a pederastic relationship: he had to be kalos (καλός), "handsome", and agathos (ἀγαθός), "good, brave, just and modest". The boy was expected to be circumspect and not let himself be easily won. Generally, the role of the lover had many of the characteristics of that of legal guardian, similar to the role of male relatives of the boy.

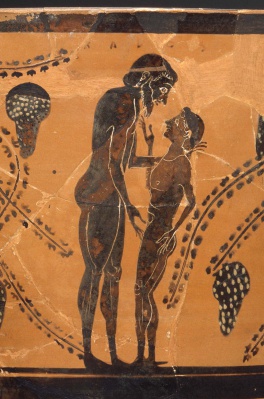

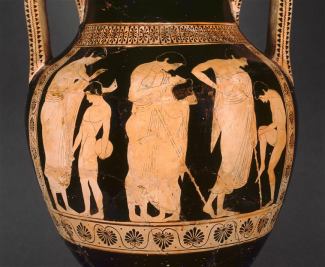

Poets such as Theognis and Anacreon self-identify as pederasts, each thus presenting a persona embodying his own ideals for the tradition. In the case of Theognis, pederasty is political and pedagogical—the elite male's method of passing on his wisdom and loyalties to his beloved. Anacreon's values are erotic and Dionysiac, which is to say sensual and spiritual, and no less ideal than those of Theognis. Vase iconography of the period is consistent with this interpretation: the gifts offered, and the context of the palaestra speak of pedagogic values, while the repeated inscriptions of "KALOS" idealize the beauty and physical attraction of the erōmenos (the beloved boy).[7]

Problematics

Michel Foucault declared that pederasty was "problematized" in Greek culture, being "the object of a special—and especially intense—moral preoccupation", focusing on concern with the chastity/moderation of the eromenos. Foucault's conclusions, however, are now thought to hold true only of Classical Athenian texts, while in Archaic Greece pederasty, rather than being problematized, was variously associated with the highest ideals.[8]

The study of Greek pederasty is complicated by the fact that the pederastic record has been subject to systematic destruction since antiquity. Of all the Greek works dealing principally with love between people of the same sex, none has survived, suggesting to at least one historian that "queer works were deliberately suppressed and destroyed rather than merely lost during the passage of time",[4] though in general only a small percentage of ancient literature has been preserved. Nonetheless, there are some conspicuous exceptions to the general picture such as the Paidikē Mousa of Strato and the Erōtes of Pseudo-Lucian.

Evolution and extinction

Greek pederasty went through a series of changes over the millennium, from its entry into the historical record to its final demise as an official institution. In some areas, such as Athens, the construction of the relationship seems to have gone from greater modesty in the early days to a freer physicality and lack of restraint in classical times, followed by a return to a more spiritual form in the early 5th century. Its formal end resembled its beginning, in that it came by official decree—that of emperor Justinian, who also put an end to other institutions that sustained ancient culture, such as Plato's Academy and the Olympic Games.

Philosophical discourses

- Main article: Philosophy of Greek pederasty

Socrates, Plato, Aeschines Socraticus, and Xenophon described the inspirational powers of love between men though decrying its physical expression. Upon the death of Plato the presidency of the Academy passed from lover to lover. Of the Stoics, Chrysippus, Cleanthes, and Zeno fell in love with young men. The topic of pederasty was the subject of extensive analysis. Some of the principal dilemmas discussed were:

- Which form should pederasty take, chaste or erotic?

- Is pederasty right or wrong?

- Is pederasty better or worse than the love of women?

Socrates, as represented in Plato's writings, appears to have favored chaste pederastic relationships, marked by a balance between desire and self-control. By setting aside the sexual consummation of the relationship, Socrates essentialized the friendship and love between the partners. He pointedly criticized purely physical infatuations, for example by mocking Critias' lust for Euthydemus by comparing his behavior towards the boy to that of a "a piglet scratching itself against a rock".[9] That, however, did not prevent him from frequenting the boy brothels, from which he bought and freed his future friend and student, Phaedo, nor from describing his erotic intoxication upon glimpsing the beautiful Charmides' naked body beneath his open tunic.[10]

Socrates' love of Alcibiades, which was more than reciprocated, is held as an example of chaste pederasty. Plutarch and Xenophon, in their descriptions of Spartan pederasty, state that even though it is the beautiful boys who are sought above all others (contrary to the Cretan traditions), nevertheless, the pederastic couple remains chaste.

Male relationships were represented in complex ways, some honorable and others dishonorable. But for the vast majority of ancient historians, for a man to have not had a youth for a lover presented a deficiency in character. Plato, in his early works (such as the Symposium and Phaedrus), does not question the principles of pederasty and states, referring to same-sex relationships:

- For I know not any greater blessing to a young man who is beginning in life than a virtuous lover, or to a lover than a beloved youth. For the principle, I say, neither kindred, nor honor, nor wealth, nor any motive is able to implant so well as love. Of what am I speaking? Of the sense of honor and dishonor, without which neither states nor individuals ever do any good or great work… And if there were only some way of contriving that a state or an army should be made up of lovers and their loves, they would be the very best governors of their own city, abstaining from all dishonor and emulating one another in honor; and it is scarcely an exaggeration to say that when fighting at each other’s side, although a mere handful, they would overcome the world.[11]

Later, however, in his Laws, Plato spoke up against the decadence into which traditional Athenian pederasty was sinking, blamed pederasty for promoting civil strife and driving many to their wits' end, and recommended the prohibition of sexual intercourse with boys, laying out a path whereby this may be accomplished.[12]

Other writers, often under the guise of "debates" between lovers of boys and lovers of women, have recorded other arguments used for and against pederasty. Some, like the charge that the practice was "unnatural" and not to be found among "the lions and the bears", applied to all relationships between men and youths. Others' charges do not involve traditional pederasty, but practices devised for the sexual satisfaction of the strong at the expense of the weak. Chief among these is denouncement of the castration of captive slave boys. As Lucian has it, "Effrontery and tyrannical violence have gone as far as to mutilate nature with a sacrilegious steel, finding, by ripping from males their very manhood, a way to prolong their use".[13]

Social aspects

The erastes-eromenos relationship was fundamental to the Classical Greek social and educational system, had its own complex social-sexual etiquette and was an important social institution among the upper class.[5] Pederastic relationships were dyadic mentorships. These mentorships were sanctioned by the state, as evidenced by laws mandating and controlling such relationships. Likewise, they were consecrated by the religious establishment, as can be seen from the many myths describing such relationships between gods and heroes (Apollo and Hyacinth, Zeus and Ganymede, Heracles and Hylas, Pan and Daphnis), and between one hero and another (Achilles and Patroclus, Orestes and Pylades). It is interesting to note that the Greeks tried to project a semblance of pederasty (read: propriety) onto these last two pairs, despite a great deal of evidence that the two myths were originally intended to symbolize egalitarian relationships. In general, the pederasty described in the Greek literary sources is clearly an aristocratic institution.

Historical as well as mythographical materials suggest that pederastic relationships required the consent of the boy's father. In Crete, in order for the suitor to carry out a ritual abduction, the father had to approve him as worthy of the honor. Among the Athenians, as Socrates claims in Xenophon's Symposium, "nothing [of what concerns the boy] is kept hidden from the father, by a noble lover".[14] This is consistent with the paramount role of the Greek patriarch, who had the right of life and death over his children. It is also consistent with the importance that a son would have had for him. Besides the bond of love between them, a son was the only hope for the survival of a Greek man's name, fortune and glory. In order to protect their sons from inappropriate attempts at seduction, fathers appointed slaves named pedagogues to watch over their sons. However, according to Aeschines, Athenian fathers would pray that their sons would be handsome and attractive, with the full knowledge that they would then invariably attract the attention of men and "be the objects of fights because of erotic passions".[15]

Boys entered into such relationships in their teens, around the same age that Greek girls were given in marriage—also to adult husbands many years their senior. There was a difference between the two types of bonding: boys usually had to be courted and were free to choose their mate. Girls, on the other hand, were used for economic and political advantage, their marriages contracted at the discretion of the father and the suitor.

The function of the relationship seems to have been the introduction of the young man into adult society and adult responsibilites. To that end the mentor was expected to teach the young man or to see to his education, and to give him certain appropriate ceremonial gifts (in Crete, an ox, a suit of armor, and a chalice (from kylix, Greek for "wine cup"), signifying his empowerment in agriculture, war and religion). The bond between the two participants seems to have been based in part on mutual love and desire—usually sexually expressed—and in part on the political interests of the two families. A great deal of importance was placed on the friendship between the two, as shown by a contemporary proverb: A lover is the best friend a boy will ever have.[16] The relationships were open and public, and became part of the biography of the person. Thus, when Spartan historians wrote about a personage, they would usually indicate whom it was that he had heard or whom it was that he inspired.

For the youth—and his family—one important advantage of being mentored by an influential older man was the social networking aspect. Thus, some considered it desirable to have had many older lovers/mentors in one's younger years, both attesting to one's physical beauty and paving the way for attaining important positions in society. Typically, after their sexual relationship had ended and the young man had married, the older man and his protégé would remain on close terms throughout their life. For those lovers who continued their lovemaking after their beloveds had matured, the Greeks made allowances, saying, You can lift up a bull, if you carried the calf.[17]

Pederasty was the idealized form of an age-structured homoeroticism that, like all social institutions, had other, less idyllic, manifestations, such as prostitution or the use of one's slave boys. However, certain forms were prohibited, such as slaves penetrating freemen, or paying free boys or young men for sex. Free youths who did sell their favors were generally ridiculed, and later in life were prohibited from performing certain official functions.

A prosecution by an Athenian politician, Aeschines, in 346 BC, Against Timarchus, is an example of how these regulations were used to political advantage. In his speech, Aeschines argues against further allowing Timarchus, an experienced middle-aged politician, his political rights, on account of his having spent his adolescence as the kept boy of a series of wealthy men. Aeschines won his case, and Timarchus was sentenced to atimia(disenfranchisement). But Aeschines is careful to acknowledge what seemingly all Athens knows: his own dalliances with beautiful boys, the erotic poems he dedicated to these youths, and the scrapes he has gotten into as a result of his affairs, none of which—he hastens to point out—were mediated by money.

Even when lawful, it was not uncommon for the relationship to fail, as it was said of many boys that they "hated no one as much as the man who had been their lover". Likewise, the Cretans required the boy to declare whether the relationship had been to his liking, thus giving him an opportunity to break it off if any violence had been done to him.

Synergy with sports

The institution of pederasty was inseparable from that of organized sports. The main venue for men and boys to meet and spend time together, and for the men to educate the boys in the arts of warfare, sports, and philosophy was the gymnasium, which was preeminently the training ground for these disciplines, and one of the principal venues for pederastic relationships. In particular, the practice of exercising nude was held to be of the utmost importance in the cult of beauty and eros which permeated pederastic societies. "The cities which have most to do with gymnastics", is the phrase which Plato uses to describe the states where Greek love flourished.[18] "Gymnastics" (from the Greek gymnos, "nude"), in this instance, conveys not only the sense of athletic discipline, but also the fact that all these exercises were taken by men and boys who were naked, and thus especially liable to be excited by physical beauty.

The beauty and erotic power of the naked body was highlighted by the custom of oiling one's body for exercise. The provision of oil for such decoration was the greatest expense of a gymnasium, and had to be heavily subsidized by the public coffers or private donors. The practice itself varied over time: in the early days it was said that modesty prevented the boys from drawing attention to their sexuality by oiling themselves below the waist. Such restraint was presumably cast by the wayside by Plato's time.

The relationship between a trainer and his athletes often had an erotic dimension, and the same place which served as training ground served equally for erotic dalliances, as can be seen from the many scenes of seduction and lovemaking depicting implements found at palaestrae, such as sponges and strigils.

Educational and military aspects

Ancient writers, as well as modern historians such as Bruce Thornton, hold that the goal of paiderastia was pedagogical, the channeling of eros into the creation of noble and good citizens. The various mythographical materials available suggest religious training (see the story of Tantalus, Poseidon, and Pelops) as well as military training (Hercules and Hylas). The theme of learning to drive a war chariot occurs repeatedly (Poseidon and Pelops, Laius and Chrysippus). Apollo is said to have taught Orpheus, one of his beloveds, to play the harp. And Zeus had Ganymede serve nectar, a theme with religious connotations. It is thus plausible to assume that even as the loves of the gods paralleled and symbolized those of the mortals, their pedagogy pointed to aspects of the educational process that took place between a lover and his beloved.

In talking about the Cretan rite, the historian Ephorus informs us that the man (known as philetor, "befriender") took the boy (known as kleinos, "glorious") into the wilderness, where they spent several months hunting and feasting with their friends. If the boy was satisfied with the conduct of his would-be comrade, he changed his title from kleinos to parastates (comrade and bystander in the ranks of battle and life), returned to the philetor and lived in close bonds of public intimacy with him. Ephorus' account does not discuss the educational aspects of the sojourn. However, this is clearly a coming-of-age rite culminating in a major ceremony upon the return of the pair from the mountains, and a process of acculturation into male society is implied.[19] (see Xenophon's Constitution of the Lacedaemonians[6] for Athenian practices and philosophy).

Military function

Military training was inseparable from the other educational aspects of pederasty, since the times of the Ancient Greeks were marked by continuous warfare, both internal and external. Martial prowess was held in the highest esteem, and one of the principal functions of pederastic relationships was the cultivation of bravery and fighting skills.

Sexual aspects

Ancient sources suggest a range of sexual activity. Cicero, describing Spartan customs, suggests that relations were expected to stop short of consummation, "The Lacedaemonians, while they permit all things except outrage hybris in the love of youths, certainly distinguish the forbidden by a thin wall of partition from the sanctioned, for they allow embraces and a common couch to lovers".[20] On the other hand, one Athenian term for sodomy was "to do it the Lacedemonian way". Literary sources are a lot more risqué, especially ancient comedy. For example, Aristophanes' parody of Ganymede riding on the back of Zeus in eagle form , in Peace, has his character ride to Olympus on the back of a dung beetle, a scatological pun on anal sex. Some modern historians, such as Bruce Thornton, conclude that whether the relationship was consummated or not probably depended on the partners.

The majority of ceramic paintings depict the older partner importuning the younger, in a variation of the Greek gesture for pleading. Normally the supplicant embraced the knees of the person whose favor he sought, while grasping the man's chin so as to look into his eyes. Pederastic art usually shows the man standing, grasping the boy's chin with one hand and reaching to fondle his genitals with the other. The boys are shown in varying degrees of rejecting or accepting the man's attentions. Less frequently, intercrural intercourse is depicted, where the erastes is shown inserting his penis between the thighs of the younger one. Only very rarely is anal sex suggested or shown, though there are literary and epigraphic indications suggesting that it was more common.

All this was claimed to be endured by the youth without physical excitement. K. J. Dover states that the eromenos was not "supposed" to feel desire for the erastes, as that would be unmanly.[21] More recent evidence suggests that in actual practice (as opposed to theory) there was, in fact, reciprocation of desire. As Thomas Hubbard points out in a critique of David Halperin's contention that boys were not aroused, some vases do show boys as being sexually responsive, and "fondling a boy's organ" (cf. Aristophanes, Birds 142) was one of the most commonly represented courtship gestures on the vases: "What can the point of this act have been unless lovers in fact derived some pleasure from feeling and watching the boy's developing organ wake up and respond to their manual stimulation?".[7]

The theme of mutuality of desire was a topic of discussion in ancient times as well. While the passive role was seen as problematic, to be attracted to men was often taken as a sign of masculinity, and it was thought that the boys who most sought the company and affections of men were the most likely to be successful in life.

Religious aspects

Myths provide more than fifty examples of young men who were the lovers of gods.[22] Poets and traditions ascribe Zeus, Poseidon, Apollo, Orpheus, Hercules, Dionysus, Hermes, and Pan to such love. All the main gods of the pantheon except Ares had these relationships.

Mythographic material suggests that the initiate experienced ecstatic states of spirit journey, leading to mystic death and transfiguration, analogous to practices still reported today in shamanic work. If so, by the 5th century BC the Greeks had forgotten the connection. In 476 BC, the poet Pindar, in his Olympian Ode I, claims to be horrified by suggestions that the gods would eat human flesh—in this context, an obvious shamanic metaphor. An opposite theory (discussed by Murray in his Homosexualities) gives credence to the texts that credit (or blame) the Cretans with its origination (Aristotle et al.), and notes the anomaly of an apparent path of diffusion radiating from Crete, while the areas (in the north of Greece) closest to the Indo-European sources are not known to have institutionalized the practice.

Myths also were a vehicle for conveying a set of moral standards for such relationship. In the myth of Zeus and Ganymede, when Zeus sends gifts and assurances to Tros, king of Troy and father of Ganymede, the ancients were reminded that even the king of Heaven must show consideration to the father of the eromenos. Many of the other pederastic myths likewise incorporate the presence of the father, suggesting an essential role for the father in these relationships. The myths also spoke directly to the youths, as is shown by a recently discovered version of the Narcissus myth. This, a more archaic version than the one related by Ovid in his Metamorphoses, is a moral tale in which the proud and unfeeling Narcissus is punished by the gods for having spurned all his male suitors.[8]

Political aspects

The state benefitted from these relationships, according to the statements of ancient writers. The friendship functioned as a restraint on the youth, since if he committed a crime, it was not he but his lover who was punished. In the military the lovers fought side by side, with each vying to shine before the other. Thus, it was said that an army of lovers would be invincible, as was the case until the battle of Chaeronea with the Theban Sacred Band, a battalion of one hundred and fifty warriors, each aided by his beloved charioteer.

Pederastic couples were also said to be fundamental to democracy and feared by tyrants, because the bond between the friends was stronger than that of obedience to a tyrannical ruler. Athenaeus states that "Hieronymus the Aristotelian says that love with boys was fashionable because several tyrannies had been overturned by young men in their prime, joined together as comrades in mutual sympathy". He gives as examples of such pederastic couples, the Athenians Harmodius and Aristogeiton, who were credited (perhaps symbolically) with the overthrow of the tyrant Hippias and the establishment of the democracy, and also Chariton and Melanippus. Others, such as Aristotle, claimed that some states encouraged pederasty as a means of population control, by directing love and sexual desire into non-procreative channels, a feature of pederasty also employed by other cultures.[23]

Political leaders Solon, Peisistratus, Hippias, Hipparchus, Themistocles, Aristides, Critias, Demosthenes, and Aeschines of Athens; Pausanias, Lysander, and Agesilaus of Sparta; Polycrates of Samos; Hieron and Agathocles of Syracuse; Epaminondas and Pelopidas of Thebes; and Archelaus, Philip II, and Alexander of Macedon were recorded to have had same-sex relationships.

Regional characteristics

The structure of pederastic practices varied from one polis to another, differences that often became the basis of competition or denigration between the cities. For example, the character of Pausanias in Plato's Symposium unfavorably compares regions such as Elis and Boeotia, where men are "unskilled in speech" and boys are permitted to yield uncritically, or Ionia, where boys are forbidden to yield, to the superior pederasty of Athens and Sparta, where men are well versed in the art of rhetoric and boys relate critically to their suitors, choosing only the most persuasive.

Athens

- Main article: Athenian pederasty

The founder of the pederastic tradition in Athens is said to be the lawgiver Solon, who also composed poetry praising the love of boys. The lover was known as the erastes, and his young partner as the eromenos or paidika. High society generally encouraged the erastes to pursue a boy to love. At the same time, the boy and his family were expected to be selective and not yield too easily.

Pederastic affairs were the butt of jokes for the commoners. Athenian philosophers, around the end of the 5th century BC, prompted by a discomfort with the lack of self-restraint and crude sexuality of some pederastic relationships, elaborated a philosophy of pederasty that valorized chaste pederastic relations.

Chalkis

Chalkis was also known in Greece as one of the centers of pederasty, leading the Athenians to jocularly use the verb chalkidizein for "sodomize". In talking about the origin of the Ganymede myth, Athenaeus claims that "the Chalcidians assert that Ganymede was carried off by Zeus in their own country, and they point out the place, calling it Harpagion". Initially the Chalcidians were said to have frowned on pederasty. However, being in military straits in a war against the Eretrians, they called for the aid of a warrior named Cleomachus. Cleomachus brought his eromenos along. In sight of the boy he displayed great bravery, leading the Chalcidian charge against the Eretians, bringing victory to the Chalcidians at the cost of his own life. The Chalcidians erected a tomb for him in their marketplace and from that time on began to honor pederasty. Aristotle attributed a popular local song to the event:

Ye lads of grace and sprung from worthy stock,

Grudge not to bravemen converse with your beauty:

In cities of Chalcis, Love, looser of limbs

Thrives side by side with courage.

Crete

- Main article: Cretan pederasty

The Cretans, a Dorian people described by Plutarch as renowned for their moderation and conservative ways, practiced an archaic form of pederasty in which the man enacted a ritual kidnapping of a boy of his choosing, with the consent of the boy's father.

Aristotle states that it was king Minos who established pederasty as a means of population control on the island community. This custom was highly regarded, and it was considered shameful for a youth to not acquire a male lover. These same Cretans were credited with introducing the myth of Zeus kidnapping Ganymede to be his lover in Olympus—though even the king of the gods had to make amends to the father.

Ionia and Aeolia

Most of the early pederastic elegiac poets, with the exception of Theognis and Tyrtaeus, were of Aeolian and Ionian descent. Unlike the warlike mainland Greeks, these were sailors and merchants. They seem to have transformed the compulsory Doric pederasty of martial apprenticeship into an elective, intellectual undertaking, and indulged in it extensively.

Their tradition featured poets such as Anacreon, and Alcaeus, a man also reputed for his bravery and political skills, who composed many of the sympotic skolia that were to become later part of the mainland tradition. Unlike the Dorians, where a lover would usually have only one eromenos, in the East a man might have several eromenoi over the course of his life. From the poems of Alcaeus we learn that the lover would customarily invite his eromenos to dine with him.[24] However, once Ionia was annexed by the Persians, the practice was outlawed. This was regarded as reflecting moral weakness. On one hand it revealed the rulers' greed for power—thus their suppression of customs likely to lead to strong friendships and inquisitive minds, the product of love. On the other, it revealed the cowardice of the subjects.[25]

Megara

One of the first cities after Sparta to be associated with the custom of athletic nudity, Megara was home to the runner Orsippus, who was famed as the first to run the footrace naked at the Olympic games and "first of all Greeks to be crowned victor naked".[26][27]

Megara was also the home of the poet Theognis, among whose works are many pederastic compositions, often addressed to his beloved Cyrnus. In his work he associates naked athletics with pederasty:

Happy is the lover who works out naked

And then goes home to sleep all day with a beautiful boy.[28]

Many critics hold that his is not the work of a single poet but represents "several generations of wisdom poetry". The poems are "social, political, or ethical precepts transmitted to Cyrnus as part of his formation into an adult Megarian aristocrat in Theognis' own image".[29]

It has been noted that in the 7th century BC, when pederasty is postulated to have first been formalized in Dorian cities, Megara cultivated good relations with Sparta, and may have been culturally attracted to emulate Spartan practices.[30]

Another poet, Theocritus, describes a local kissing contest for boys:

And ye Megarians, at Nesaea dwelling,

Expert at rowing, mariners excelling,

Be happy ever! for with honors due

Th' Athenian Diocles, to friendship true

Ye celebrate. With the first blush of spring

The youth surround his tomb: there who shall bring

The sweetest kiss, whose lip is purest found,

Back to his mother goes with garlands crowned.

Nice touch the arbiter must have indeed,

And must, methinks, the blue-eyed Ganymede

Invoke with many prayers—a mouth to own

True to the touch of lips, as Lydian stone

To proof of gold—which test will instant show

The pure or base, as money changers know.[31]

Sparta

- Main article: Spartan pederasty

Sparta, another Dorian polis, is thought to be the first city to practice athletic nudity, and one of the first to formalize pederasty.[32] The Spartans believed that the love of an older, accomplished aristocrat for an adolescent was essential to his formation as a free citizen. The agoge, the education of the ruling class, was thus founded on pederastic relationships required of each citizen.[33]

Many ancient writers held that Spartan pederasty was chaste, though still erotic.[34] Plutarch also describes the relationships as chaste, and states that it was as unthinkable for a lover to sexually consummate a relationship with his beloved as for a father to do so with his own son.[35] Aelian goes even farther, stating that if any couple succumbed to temptation and indulged in carnal relations, they would have to redeem the affront to the honor of Sparta by either going into exile or taking their own lives.[36]

The lover was responsible for the boy's training. Pederasty and military training were intimately connected in Sparta, as in many other cities. The Spartans, claims Athenaeus[37], sacrificed to Eros before every battle.

Thebes

- Main article: Theban pederasty

In Thebes, the main polis in Boeotia, renowned for its practice of pederasty, the tradition was enshrined in the founding myth of the city. In this instance, the story was meant to teach by counterexample: it depicts Laius, one of the mythical ancestors of the Thebans, in the role of a lover who betrays the father and rapes the son. Another Boeotian pederastic myth is the story of Narcissus.

Theban pederasty, was instituted as an educational device for boys, in order to "soften, while they were young, their natural fierceness", and to "temper the manners and characters of the youth".[38] The Sacred Band of Thebes, a battalion made up of 150 pairs of lovers, was unbeatable until its final battle against Phillip II at Chaeronea in 338 BC.

Influence on literature and the arts

Poets wrote of pederasty from the earliest eras to the end of the Hellenistic era. Five philosophical dialogues debate its ethical implications. Notable scholars and writers such as Plato, Xenophon, Plutarch, and Pseudo-Lucian would discuss the topic. Tragedies on the theme became very popular. Aristophanes made comical theater about sexual relationships between men and youths.

The famous poets Alcaeus, Ibycus, Anacreon, Theognis, Pindar and Sappho, all wrote of pederastic love. Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides made plays on the subject.

Vases portray numerous homoerotic depictions, with hundreds of inscriptions celebrating the love of youths. Famous politicians, warriors, artists, and writers would enjoy these relationships. Such idealized relationships held an honored place in their culture from at least 600 BC to 400 AD.

The sculptor Phidias even memorialized his lover Pantarces in marble by inscribing his name on the finger of a colossal statue of Zeus. During the Hellenistic era (332 BC–400 AD), Plutarch, Athenaeus, and Aelian traced the history of Greek homosexuality to its beginning.

Ceremonies and proverbs

- Oath of loyalty at the tomb of Iolaus in Thebes; rite undertaken by lovers to consecrate the relationship.[39]

- The Iolaeia, a yearly athletic festival in Thebes, consisting of musical, gymnastic and equestrian events (agones). It was held in the gymnasium of Iolaus in honor of Heracles, and lasted several days. The winners were awarded brass tripods.[40]

- The Hyacinthia festival in Sparta, honoring Hyacinth, the mythical young prince of Sparta and beloved of Apollo. The festivities continued for three days, with the first mourning the death of Hyacinthus and the last two celebrating his rebirth. It has been suggested that the cycle symbolizes the development of a youth in such relationships, in which he dies as a child in order to be reborn as an adult.

- Gymnopaedia; Spartan dances by naked boys, attendance restricted to married men.

- The Diocleia festival at Megara in honour of Diocles, lover of Philolaus; a kissing contest was held in which the boys would kiss a male judge, with a wreath awarded to the one with the best kiss.[41]

- A lover is the best friend a boy will ever have.[42]

- You can carry a bull, if you carried the calf. Also in Ancient Rome, as Taurum tollet, qui vitulum sustulerit. Said to excuse men's relations with "boys" who were no longer adolescents.[43]

Modern scholarship

The ethical views held in those societies (such as Athens, Thebes, Crete, Sparta, Elis, and others) on the practice of pederasty have been explored by scholars only since the end of the 19th century. One of the first to do so was John Addington Symonds, who wrote his seminal work A Problem in Greek Ethics in 1873, but had to wait twenty eight years to be able to publish it (in revised form) in 1901.[9] Edward Carpenter expanded the scope of the study with his 1914 work, Intermediate Types among Primitive Folk. The text examines homoerotic practices of all types, not only pederastic ones, and ranges over cultures spanning the whole globe.[10] In Germany the work was continued by classicist Paul Brand, writing under the pseudonym Hans Licht, who published his Sexual Life in Ancient Greece in 1932.

Mainstream Ancient Greek studies, however, had historically omitted references of the widespread practice of homosexuality. In 1910, the novel Maurice by E. M. Forster made reference to this "code of silence" by having a Cambridge professor employing "Omit: a reference to the unspeakable vice of the Greeks". Four decades later, in the 1940s: "This aspect of Greek morals is an extraordinary one, into which, for the sake of our equanimity, it is unprofitable to pry too closely", by H. Michell. It would not be until 1978 when an English book on this topic, titled Greek Homosexuality, was published by K. J. Dover.

Dover's work triggered a number of debates which still continue. At the most basic level, there is strong resistance among modern Greeks to the portrait of ancient Greece painted by modern scholarship—that of a culture which integrated and valorized some aspects of same sex love for a period lasting close to one thousand years.

A modern line of thought leading from Dover to Foucault to Halperin holds that the eromenos did not reciprocate the love and desire of the erastes, and that the relationship was factored on a sexual domination of the younger by the older, a politics of penetration held to be true of all adult male Athenians' relations with their social inferiors—boys, women and slaves—a theory propounded also by Eva Keuls.[44] From this perspective, the relationships are characterized and factored on a power differential between the participants, and as essentially asymmetrical.

Other scholars point to artwork on vases, poetry and philosophical works such as the Platonic discussion of anteros, "love returned", all of which show tenderness and desire and love on the part of the eromenos matching and responding to that of the erastes. Critics of Dover and his followers also point out that they ignore all material which argued against their "overly theoretical" interpretation of a human and emotional relationship[45] and counter that "clearly, a mutual, consensual bond was formed",[46] and that it is "a modern fairy tale that the younger eromenos was never aroused".[47]

Halperin's position has been criticized as a "persistently negative and judgmental rhetoric implying exploitation and domination as the fundamental characteristics of pre-modern sexual models" and challenged as a polemic of "mainstream assimilationist gay apologists" and an attempt to "demonize and purge from the movement" all non-orthodox male sexualities, especially that involving adults and adolescents.[48]

Notes

- ↑ Nick Fisher, Aeschines: Against Timarchos, "Introduction", p. 27; Oxford University Press, 2001.

- ↑ K. J. Dover, Greek Homosexuality; Harvard University Press, 1989; p. 50.

- ↑ Nick Fisher, Aeschines: Against Timarchos, "Introduction", p. 26; Oxford University Press, 2001.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 William Armstrong Percy III, "Reconsiderations about Greek Homosexualities", in Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West, Binghamton, 2005; pp. 47.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Plato, Symposium, 182A.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, 2.12–14.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 "Many of the gifts offered by erastai to eromenoi in vase-painting (hares, lyres, etc.) have pedagogical associations, as do other elements of costume and setting which connect pederastic scenes to athletics and the hunt: thus, like the Theognidea, vase-painting portrays pederasty as pedagogical. Other aspects of this iconography, however, emphasize the erotic/Dionysiac aspects of pederasty; kalos inscriptions, for instance, emphasize the importance in it of beauty—and hence desire. Yet as in Anacreon, the presence of the erotic does not detract from pederasty's idealized status: several crucial elements in vase-painting symbolize the sexual moderation of the lovers". Andrew Lear, "The Idealization of Pederasty in Archaic Greek Poetry and Vase-Painting", American Philological Association abstract.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Andrew Lear, "The Idealization of Pederasty in Archaic Greek Poetry and Vase-Painting", delivered at the 2005 American Philological Association Annual Meeting.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Xenophon, Memorabilia, 1.2.29–30.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 Plato, Charmides, 155c–e.

- ↑ Plato, Phaedrus in the Symposium.

- ↑ Plato, Laws, 636D & 835E.

- ↑ Pseudo-Lucian, Erotes.

- ↑ Xenophon, Symposium, IIX.24.

- ↑ Victoria Wohl, Love among the Ruins: The Erotics of Democracy in Classical Athens, p. 5, referring to Aeschines, (Tim. 134).

- ↑ Plato, Phaedrus, 231.

- ↑ Andrew Calimach, Lovers' Legends: The Gay Greek Myths.

- ↑ Plato, Laws, I; 636 C.

- ↑ Ephorus, quoted in Strabo of Amaseia's Geography, X.4.21.

- ↑ Cicero, De Rep., IV. 4.

- ↑ K. J. Dover, Greek Homosexuality.

- ↑ Bernard Sergent, Homosexuality and Greek Myth, passim.

- ↑ Athenaeus, Deipnosophists, 602.

- ↑ Percy, William A., Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece, pp. 146–150.

- ↑ Plato, Symposium, 182c–d.

- ↑ W. Sweet, Sport and Recreation in Ancient Greece, 1987; p. 125

- ↑ Pausanias, 1.44.1.

- ↑ Theognis, 1335–36.

- ↑ Thomas K. Hubbard, Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents, University of California, 2003; p. 23.

- ↑ N.G.L. Hammond, A History of Greece to 322 BC, 1989; p. 150.

- ↑ Theocritus, "Idyll XII", tr. Edward Carpenter.

- ↑ Thomas F. Scanlon, "The Dispersion of Pederasty and the Athletic Revolution in Sixth-Century BC Greece", in Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West, ed. B. C. Verstraete and V. Provencal, Harrington Park Press, 2005, pp. 64–70.

- ↑ Erich Bethe, Die Dorische Knabenliebe: ihre Ethik und ihre Idee, 1907, 441, 444.

- ↑ Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, II.13–14.

- ↑ Cicero, De Rep., IV. 4

- ↑ Aelian, Var. Hist., III.12.

- ↑ Athenaeus of Naucratis, The Deipnosophists, XIII: Concerning Women.

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Pelopidas.

- ↑ Plutarch, Eroticus, cap. XVII.

- ↑ Pindar, Olympian Ode, VIII, 84.

- ↑ Theocritus, "Idylls" 12–30.

- ↑ Plato, Phaedrus, 231.

- ↑ Petronius, The Satyricon, III.67.

- ↑ Eva Keuls, The Reign of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens, 1985.

- ↑ James Davidson, The Greeks and Greek Love, Orion, 2006.

- ↑ Robert B. Koehl, "Ephoros and Ritualized Homosexuality in Bronze Age Crete", in Queer Representations: Reading Livers, Reading Cultures, Martin Duberman, ed. New York University, 1997.

- ↑ Hein van Dolen, "Greek Homosexuality".

- ↑ Thomas K. Hubbard, "Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2003.09.22" of David M. Halperin's How to Do the History of Homosexuality.

See also

References

General

- Growing Up Sexually: A World Atlas, edited by D. F. Janssen.

- Studies in the Psychology of Sex, Vol. 2: Sexual Inversion, by Havelock Ellis.

Ancient Greece

- Greek Homosexuality by Kenneth J. Dover; Duckworth 1978 ISBN 0-7156-1464-9

- Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece by William A. Percy; Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996. ISBN 0-252-02209-2

- Die Griechische Knabenliebe [Greek Pederasty] by Harald Patzer; Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1982. In: Sitzungsberichte der Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft an der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main, Vol. 19 No. 1.

- Homosexuality in Greek Myth by Bernard Sergent; Beacon Press, 1986. ISBN 0-8070-5700-2

- Homosexualité et initiation chez les peuples indo-européens, by Bernard Sergent, Payot & Rivages, 1996. ISBN 2-228-89052-9

- Lovers' Legends: The Gay Greek Myths by Andrew Calimach; Haiduk Press, 2001. ISBN 0-9714686-0-5

- Lovers' Legends Unbound, by Andrew Calimach et al.; Haiduk Press, 2004. ISBN 0-9714686-1-3

- Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents by Thomas K. Hubbard; U. of California Press, 2003. ISBN 0-520-23430-8