Pederastic relationships in classical antiquity: Difference between revisions

Added an internal link |

|||

| (7 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

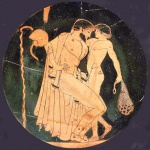

[[File:Harmodius and Aristogiton.jpg|thumb|right|[[Harmodius and Aristogeiton]]]] | |||

In classical antiquity there were many known [[pederastic]] relationships. Though most involved adult men and adolescent boys, the age difference between the two could be as little as a couple of years, and an older youth (neaniskos) could take a younger one as his beloved.<ref>Homoeroticism in the Biblical World By Martti Nissinen, Kirsi Stjerna; p67</ref> In some of these cases both members became well-known historical figures, while in others, only one of the two may have, or only the relationship itself. The vast majority presumably never attracted the attention of any author whose writings have survived. | In classical antiquity there were many known [[pederastic]] relationships. Though most involved adult men and adolescent boys, the age difference between the two could be as little as a couple of years, and an older youth (neaniskos) could take a younger one as his beloved.<ref>Homoeroticism in the Biblical World By Martti Nissinen, Kirsi Stjerna; p67</ref> In some of these cases both members became well-known historical figures, while in others, only one of the two may have, or only the relationship itself. The vast majority presumably never attracted the attention of any author whose writings have survived. | ||

Though all such relationships were by definition homoerotic in nature, the individuals involved did not identify themselves as [[homosexual]]s -- at the time no one did -- but rather as ordinary men with ordinary, healthy desires. The nature of the relationships ranged from overtly sexual to what is now referred to (inaccurately) as platonic, in accordance with ancient ethical and philosophical standards.<ref> Hubbard, Thomas K. "Introduction" to ''Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003. pg. 9.</ref> | Though all such relationships were by definition homoerotic in nature, the individuals involved did not identify themselves as [[homosexual]]s -- at the time no one did -- but rather as ordinary men with ordinary, healthy desires. The nature of the relationships ranged from overtly sexual to what is now referred to (inaccurately) as platonic, in accordance with ancient ethical and philosophical standards.<ref> Hubbard, Thomas K. "Introduction" to ''Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003. pg. 9.</ref> | ||

In the following list the pairs are listed in chronological order, and the name of the older partner precedes that of the younger. Though many more men are known to have engaged in such relationships, only those instances in which the name of the younger partner is known are included. In keeping with ancient traditions which promoted chaste pederastic relationships (See [[Philosophy of Greek pederasty]]) included below are also relationships in which there is evidence of an erotic component even in the absence of actual sexual relations. | In the following list the pairs are listed in chronological order, and the name of the older partner precedes that of the younger. Though many more men are known to have engaged in such relationships, only those instances in which the name of the younger partner is known are included. In keeping with ancient traditions which promoted chaste pederastic relationships (See [[Philosophy of Greek pederasty]]) included below are also relationships in which there is evidence of an erotic component even in the absence of actual sexual relations.{{History}} | ||

==Ancient Greece== | ==Ancient Greece== | ||

| Line 18: | Line 13: | ||

*'''[[Archias of Corinth]] and Telephus''' | *'''[[Archias of Corinth]] and Telephus''' | ||

Archias is a semi-legendary personage, the richest man in Corinth and the colonizer of Syracuse in 733 BCE. He left his native city as penance for having caused the death of Actaeon, "the loveliest and most modest of all the striplings of his age", son of Melissus of Argos. Archias fell in love with the boy, who rejected his advances, as he was already the beloved of Aeschyllus of Corinth <ref>Meier, ''L'Amour grec'', p. 161</ref>. Gathering his servants, he stormed the boy's house. The family and neighbors resisted and in the altercation Actaeon was torn apart. Telephus is another ''[[eromenos]]'' of Archias, who, in maturity, captained one of the ships that Archais used to cross to Sicilly and there slew Archias by some subterfuge, to avenge himself for having been taken advantage of when he had been the man's paidika. <ref>Plutarch, Amatorius 2)(Diodorus Siculus, Excerpt de virtut. 8.8</ref> | ::Archias is a semi-legendary personage, the richest man in Corinth and the colonizer of Syracuse in 733 BCE. He left his native city as penance for having caused the death of Actaeon, "the loveliest and most modest of all the striplings of his age", son of Melissus of Argos. Archias fell in love with the boy, who rejected his advances, as he was already the beloved of Aeschyllus of Corinth <ref>Meier, ''L'Amour grec'', p. 161</ref>. Gathering his servants, he stormed the boy's house. The family and neighbors resisted and in the altercation Actaeon was torn apart. Telephus is another ''[[eromenos]]'' of Archias, who, in maturity, captained one of the ships that Archais used to cross to Sicilly and there slew Archias by some subterfuge, to avenge himself for having been taken advantage of when he had been the man's paidika. <ref>Plutarch, Amatorius 2)(Diodorus Siculus, Excerpt de virtut. 8.8</ref> | ||

*'''[[Philolaus]] and Diocles of Corinth''' | *'''[[Philolaus]] and Diocles of Corinth''' | ||

Philolaus was a memebr of the Bacchiadae, a ruling clan in Corinth, and a nomothete (lawgiver) of Thebes, Greece|Thebes, giving them the adoption laws. His [[eromenos]] won the Stadion race at the thirteenth Ancient Olympic Games of 728, which at that time only featured that one contest.The Sicilian colony dates By Molly Miller; p213 Diocles was compelled to leave Corinth and go to Thebes, perhaps as a result of being banished. Philolaus followed him, aware of the improper passion that Alcyone, his eromenos' mother, had for him. The two lived out their lives in Thebes, and were buried there together, their tombs across from each other. <ref>Commentary on Aristotle's Politics By Saint Thomas (Aquinas), Richard J. Regan; p177</ref> | ::Philolaus was a memebr of the Bacchiadae, a ruling clan in Corinth, and a nomothete (lawgiver) of Thebes, Greece|Thebes, giving them the adoption laws. His [[eromenos]] won the Stadion race at the thirteenth Ancient Olympic Games of 728, which at that time only featured that one contest.The Sicilian colony dates By Molly Miller; p213 Diocles was compelled to leave Corinth and go to Thebes, perhaps as a result of being banished. Philolaus followed him, aware of the improper passion that Alcyone, his eromenos' mother, had for him. The two lived out their lives in Thebes, and were buried there together, their tombs across from each other. <ref>Commentary on Aristotle's Politics By Saint Thomas (Aquinas), Richard J. Regan; p177</ref> | ||

*'''[[Gyges of Lydia|Gyges]] and Magnes''' | *'''[[Gyges of Lydia|Gyges]] and Magnes''' | ||

According to Nicolaus of Damascus, the Lydian tyrant (late 8th c. or early 7th c.) took as his paidika a handsome youth from Smyrna who was noted for his elegant clothes and fancy ''korymbos'' hairstyle, which he bound with a golden band. One day he was singing poetry to the local women, which outraged their male relatives, who grabbed Magnes, stripped him of his clothes and cut off his hair. <ref>Initiation in ancient Greek rituals and narratives By David Brooks Dodd, Christopher A. Faraone, p.121</ref> | ::According to Nicolaus of Damascus, the Lydian tyrant (late 8th c. or early 7th c.) took as his paidika a handsome youth from Smyrna who was noted for his elegant clothes and fancy ''korymbos'' hairstyle, which he bound with a golden band. One day he was singing poetry to the local women, which outraged their male relatives, who grabbed Magnes, stripped him of his clothes and cut off his hair. <ref>Initiation in ancient Greek rituals and narratives By David Brooks Dodd, Christopher A. Faraone, p.121</ref> | ||

*'''Anton and Philistus''' | *'''Anton and Philistus''' | ||

Alternative names, identified by Aristotle (according to Plutarch) for Cleomachus the Pharsalian and his eromenos, Thessaly|Thessalians famous for having helped the Chalkis|Chalcidians in their Lelantine War|war against the Eretrians, inspiring the Chalcidians to adopt pederasty after having previously prohibited it, some time between 700 and 650. The story goes that Cleomachus asked his eromenos if he would watch the fight. The youth answered "Yes," and helped his lover with his helmet, kissing him. Cleomachus then attacked the enemy and routed their cavalry, but lost his life. The tomb of Anton/Cleomachus was prominent in the agora in Chalcis, and a local song was sung in honor of lovers: | ::Alternative names, identified by Aristotle (according to Plutarch) for Cleomachus the Pharsalian and his eromenos, Thessaly|Thessalians famous for having helped the Chalkis|Chalcidians in their Lelantine War|war against the Eretrians, inspiring the Chalcidians to adopt pederasty after having previously prohibited it, some time between 700 and 650. The story goes that Cleomachus asked his eromenos if he would watch the fight. The youth answered "Yes," and helped his lover with his helmet, kissing him. Cleomachus then attacked the enemy and routed their cavalry, but lost his life. The tomb of Anton/Cleomachus was prominent in the agora in Chalcis, and a local song was sung in honor of lovers: | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

::O boys whom Fate has granted beauty and valiant fathers, | ::O boys whom Fate has granted beauty and valiant fathers, | ||

| Line 38: | Line 33: | ||

</poem> | </poem> | ||

An Athenian inscription of 500BCE refers to another version of this story. It reads "Here a man beloved by a boy swore an oath to join the strife of war that brings tears. I am consecrated to Gnathios whose life was lost in war, son of Heroas." On the obverse, the eromenos laments, "Gnathios, always hastening am I to greet you." <ref>Friedlander and Hoffleit, 1948, 63-4, no.59, dated 500BCE; in "Sex in the ancient world from A to Z - Page 46</ref> | ::An Athenian inscription of 500BCE refers to another version of this story. It reads "Here a man beloved by a boy swore an oath to join the strife of war that brings tears. I am consecrated to Gnathios whose life was lost in war, son of Heroas." On the obverse, the eromenos laments, "Gnathios, always hastening am I to greet you." <ref>Friedlander and Hoffleit, 1948, 63-4, no.59, dated 500BCE; in "Sex in the ancient world from A to Z - Page 46</ref> | ||

*'''Aristodemus and Cratinus''' | *'''Aristodemus and Cratinus''' | ||

Semi-legendary couple, held to have sacrificed themselves to purify Athens of a plague sent by the gods during the 44th olympiad (604-601). The Cretan sage Epimenides had been invited to help rid the Athenians of the curse, which he claimed could only be lifted by means of a blood sacrifice. Cratinus, a handsome adolescent, offered himself willingly, and he was followed by his lover, Aristodemus. The tale was doubted by some in antiquity, and held to be a fiction.<ref>Atheneaus, XIII.602d</ref> | ::Semi-legendary couple, held to have sacrificed themselves to purify Athens of a plague sent by the gods during the 44th olympiad (604-601). The Cretan sage Epimenides had been invited to help rid the Athenians of the curse, which he claimed could only be lifted by means of a blood sacrifice. Cratinus, a handsome adolescent, offered himself willingly, and he was followed by his lover, Aristodemus. The tale was doubted by some in antiquity, and held to be a fiction.<ref>Atheneaus, XIII.602d</ref> | ||

*'''Alcaeus of Mytilene and Lycos, and Menon''' | *'''Alcaeus of Mytilene and Lycos, and Menon''' | ||

The contemporary and also the presumed lover of Sappho, possibly around 600-590 BCE, Alcaeus wrote pederastic odes to his beloveds, among whom was "the handsome Lycos, with black eyes and hair.<ref>"M.-H.-E. Meier, ''Histoire de l'Amour Grec dans l'Antiquité'' p.26</ref> | ::The contemporary and also the presumed lover of Sappho, possibly around 600-590 BCE, Alcaeus wrote pederastic odes to his beloveds, among whom was "the handsome Lycos, with black eyes and hair.<ref>"M.-H.-E. Meier, ''Histoire de l'Amour Grec dans l'Antiquité'' p.26</ref> | ||

Another beloved was Menon, of whom he wrote, "I request that the charming Menon be invited, if I am to enjoy the drinking party." | ::Another beloved was Menon, of whom he wrote, "I request that the charming Menon be invited, if I am to enjoy the drinking party." | ||

*'''Solon and Peisistratus''' | *'''Solon and Peisistratus''' | ||

The Athenian law giver was said to have been the [[erastes]] of the future tyrant, born 605-600 (Matthew Dillon, Lynda Garland, Ancient Greece: social and historical documents from archaic times to the ... p117</ref>, as well as his cousin, presumably around 590-585 BCE. <ref>Plutarch, ''The Lives,'' "Solon"</ref> Aristotle, however, claims that the story is "mere gossip" and cannot possibly be true due to the large difference in age between the two (about forty years). "It is evident from this that the story is mere gossip which states that Pisistratus was the eromenos of Solon" <ref>Aristotle, ''The Athenian Constitution''</ref> | ::The Athenian law giver was said to have been the [[erastes]] of the future tyrant, born 605-600 (Matthew Dillon, Lynda Garland, Ancient Greece: social and historical documents from archaic times to the ... p117</ref>, as well as his cousin, presumably around 590-585 BCE. <ref>Plutarch, ''The Lives,'' "Solon"</ref> Aristotle, however, claims that the story is "mere gossip" and cannot possibly be true due to the large difference in age between the two (about forty years). "It is evident from this that the story is mere gossip which states that Pisistratus was the eromenos of Solon" <ref>Aristotle, ''The Athenian Constitution''</ref> | ||

*'''Peisistratus and Charmus''' | *'''Peisistratus and Charmus''' | ||

Peisistratos took Charmus of the deme Kolyttus, a syngenes (member of his extended family), as eromenos. Charmus was a life-long intimate of the Pisistratid dynasty. In middle age, in 557/6 he rose to the position of polemarch (defense minister). | ::Peisistratos took Charmus of the deme Kolyttus, a syngenes (member of his extended family), as eromenos. Charmus was a life-long intimate of the Pisistratid dynasty. In middle age, in 557/6 he rose to the position of polemarch (defense minister). | ||

*'''Chariton of Agrigentum and Melanippus''' | *'''Chariton of Agrigentum and Melanippus''' | ||

Phalaris, tyrant of Agrigentum around 565-549 BCE, attempted to seduce Melanippus, Chariton's eromenos. The two lovers plotted to avenge themselves by killing Phalaris. Chariton was discovered and tortured to divulge accomplices, but remained silent. Melanippus, to save his friend, presented himself and freely confessed. The tyrant, impressed, set both free, but sent them into exile. About them, the ''Suda'' records that "For Chariton and Melanippos breathed together in love. Chariton was the lover, but Melanippos, the beloved, his soul set on fire towards his inspired friend, made known the spur of love with equal honour.<ref>" http://www.stoa.org/sol-bin/search.pl?login=guest&enlogin=guest&db=REAL&field=adlerhw_gr&searchstr=alpha,2634 ''Suda'' a2634</ref> Their valor and love were also celebrated in a Delphic oracle: | ::Phalaris, tyrant of Agrigentum around 565-549 BCE, attempted to seduce Melanippus, Chariton's eromenos. The two lovers plotted to avenge themselves by killing Phalaris. Chariton was discovered and tortured to divulge accomplices, but remained silent. Melanippus, to save his friend, presented himself and freely confessed. The tyrant, impressed, set both free, but sent them into exile. About them, the ''Suda'' records that "For Chariton and Melanippos breathed together in love. Chariton was the lover, but Melanippos, the beloved, his soul set on fire towards his inspired friend, made known the spur of love with equal honour.<ref>" http://www.stoa.org/sol-bin/search.pl?login=guest&enlogin=guest&db=REAL&field=adlerhw_gr&searchstr=alpha,2634 ''Suda'' a2634</ref> Their valor and love were also celebrated in a Delphic oracle: | ||

::''Blessed were Chariton and Melanippus:'' | ::''Blessed were Chariton and Melanippus:'' | ||

::''They showed mortals the way to a friendship that was divine.'' <ref>Athenaeus, ''Deipnosophistai,'' 13.602</ref> | ::''They showed mortals the way to a friendship that was divine.'' <ref>Athenaeus, ''Deipnosophistai,'' 13.602</ref> | ||

According to Aelian, the facts are different: Melanippus brought a suit against a friend of Phalaris, who asked the youth to withdraw his action. He refused, but the judges refused the suit out of fear of the tyrant. Enraged, Melanippus asked Chariton's help in staging an uprising. Fearing betrayal, Chariton acted alone, was cuaght and under torture refused to name any accomplices. Melanippus stepped forward of his own accord, leading Phalaris to pardon them both, under exile but able to enjoy the profits of their estates. <ref>Var. Hist. 1.30</ref> | ::According to Aelian, the facts are different: Melanippus brought a suit against a friend of Phalaris, who asked the youth to withdraw his action. He refused, but the judges refused the suit out of fear of the tyrant. Enraged, Melanippus asked Chariton's help in staging an uprising. Fearing betrayal, Chariton acted alone, was cuaght and under torture refused to name any accomplices. Melanippus stepped forward of his own accord, leading Phalaris to pardon them both, under exile but able to enjoy the profits of their estates. <ref>Var. Hist. 1.30</ref> | ||

*'''Charmus and Hippias''' | *'''Charmus and Hippias''' | ||

After having been the eromenos of the father, Pisistratus, Charmus became, probably around 555 BCE, the erastes of the son and future tyrant, who was born in the late 570s <ref>Dillon, 117</ref>. As Charmus' daughter, Myrrhina, was exceptionally beautiful, Pisistratus chose her to be wife to Hippias, in 557/6, according to Kleidemos. | ::After having been the eromenos of the father, Pisistratus, Charmus became, probably around 555 BCE, the erastes of the son and future tyrant, who was born in the late 570s <ref>Dillon, 117</ref>. As Charmus' daughter, Myrrhina, was exceptionally beautiful, Pisistratus chose her to be wife to Hippias, in 557/6, according to Kleidemos. | ||

Charmus' son, Hipparchus, archon of 496/5, <ref>Dionysios of Halikarnassos, 5.77.6</ref>, named after his erastes' second son, was the very first Athenian to be ostracized, in 487, once the law was passed by Kleisthenes, who did so expressly to get him banished. Hipparchus was the leader and representative of the friends of the tyrants, and was agitating for the return of his brother-in-law, Hippias, exiled in 511/10, and for the appeasement of the Persians. <ref>Aristotle's Constitution of Athens, trans. Thomas J. Dymes (London: Seeley and Co., 1891) (Michael F. Arnush, "The Career of Peisistratos Son of Hippias" in ''Hesperia,'' Vol. 64, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1995), pp. 135-162</ref> | ::Charmus' son, Hipparchus, archon of 496/5, <ref>Dionysios of Halikarnassos, 5.77.6</ref>, named after his erastes' second son, was the very first Athenian to be ostracized, in 487, once the law was passed by Kleisthenes, who did so expressly to get him banished. Hipparchus was the leader and representative of the friends of the tyrants, and was agitating for the return of his brother-in-law, Hippias, exiled in 511/10, and for the appeasement of the Persians. <ref>Aristotle's Constitution of Athens, trans. Thomas J. Dymes (London: Seeley and Co., 1891) (Michael F. Arnush, "The Career of Peisistratos Son of Hippias" in ''Hesperia,'' Vol. 64, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1995), pp. 135-162</ref> | ||

In Charmus' honor, a statue of Eros was erected, either by Pisistratus or Hippias, before the entrance of the Akademia, where the runners in the sacred torch race lit their torches. The inscription noted that Charmus had been the first to dedicate to love. The votive part read: | ::In Charmus' honor, a statue of Eros was erected, either by Pisistratus or Hippias, before the entrance of the Akademia, where the runners in the sacred torch race lit their torches. The inscription noted that Charmus had been the first to dedicate to love. The votive part read: | ||

::''Eros of many devices, Charmus built you this altar'' | ::''Eros of many devices, Charmus built you this altar'' | ||

::''Among the shady boundaries of the Gymnasium.'' | ::''Among the shady boundaries of the Gymnasium.'' | ||

Clement of Alexandria, however, asserts it was Charmus who invented the cult of Eros and had the statue erected, to thank the god for the satisfactions he gained from having "carried off a young lad." <ref>Clement of Alexandria "Exhortation to the Greeks", Chap. 3, 38P</ref><ref>Plutarch,''Solon'' 1.7; Pausanias, 1.30.1; Athen., xiii. 609D; Aristotle, The Athenian Constitution, III.22</ref> | ::Clement of Alexandria, however, asserts it was Charmus who invented the cult of Eros and had the statue erected, to thank the god for the satisfactions he gained from having "carried off a young lad." <ref>Clement of Alexandria "Exhortation to the Greeks", Chap. 3, 38P</ref><ref>Plutarch,''Solon'' 1.7; Pausanias, 1.30.1; Athen., xiii. 609D; Aristotle, The Athenian Constitution, III.22</ref> | ||

*'''Prokleides and Hipparchus''' | *'''Prokleides and Hipparchus''' | ||

Prokleides, likely an Athenian notable, was erastes to Hipparchus, the younger son of Pisistratus. Later in life Hipparchus gained a reputation as erotikos, given to love affairs, and philomousos, fond of the arts. He built up a large library, and invited the poets Anacreon and Simonides to Athens. His predilections led to his death, as he was assassinated by Harmodius, a noble youth who had rejected his advances and whose family he had insulted in revenge for the rejection. Prokleides, also known as Eukleides, also is known for setting up the Hermes Trikephalos, a three-headed road-marker statue, on the Hestia Road. <ref>Rommel Mendès-Leite et al. ''Gay Studies from the French Cultures'' p.157</ref>. | ::Prokleides, likely an Athenian notable, was erastes to Hipparchus, the younger son of Pisistratus. Later in life Hipparchus gained a reputation as erotikos, given to love affairs, and philomousos, fond of the arts. He built up a large library, and invited the poets Anacreon and Simonides to Athens. His predilections led to his death, as he was assassinated by Harmodius, a noble youth who had rejected his advances and whose family he had insulted in revenge for the rejection. Prokleides, also known as Eukleides, also is known for setting up the Hermes Trikephalos, a three-headed road-marker statue, on the Hestia Road. <ref>Rommel Mendès-Leite et al. ''Gay Studies from the French Cultures'' p.157</ref>. | ||

*'''Theognis of Megara and Cyrnus''' | *'''Theognis of Megara and Cyrnus''' | ||

The poet, thought to have lived around the middle of the sixth c. BCE, addressed many of his poems to his young beloved, using them to pass on his wisdom to the boy.<ref>[http://www.laits.utexas.edu/ancienthomosexuality/readindex.php?view=9 Ed. Thomas K. Hubbard, ''Homosexuality in Greece and Rome'']</ref> | ::The poet, thought to have lived around the middle of the sixth c. BCE, addressed many of his poems to his young beloved, using them to pass on his wisdom to the boy.<ref>[http://www.laits.utexas.edu/ancienthomosexuality/readindex.php?view=9 Ed. Thomas K. Hubbard, ''Homosexuality in Greece and Rome'']</ref> | ||

*'''Timagoras and Meles''' | *'''Timagoras and Meles''' | ||

A metic (immigrant) potter around 550 to 520 BCE, Timagoras fell in love with Meles, an Athenian boy. Disdainful of the metic, a social inferior, the boy told him to go jump off the Acropolis. Timagoras was not concerned for his life and wanted to give the boy everything he asked for, so he threw himself off the cliff and was killed in the fall. Meles felt deep remorse and jumped off the same rock, losing his own life. The other immigrants raised an altar to Timagoras and worshipped him there as Anteros, the avenging spirit of his love. <ref>Pausanias I.30.1</ref><ref>Irina Kovaleva, "Eros at the Panathenaea: Personification of what?" in Emma Stafford, Judith Herrin, Personification in the Greek world: from antiquity to Byzantium. p.138</ref> | ::A metic (immigrant) potter around 550 to 520 BCE, Timagoras fell in love with Meles, an Athenian boy. Disdainful of the metic, a social inferior, the boy told him to go jump off the Acropolis. Timagoras was not concerned for his life and wanted to give the boy everything he asked for, so he threw himself off the cliff and was killed in the fall. Meles felt deep remorse and jumped off the same rock, losing his own life. The other immigrants raised an altar to Timagoras and worshipped him there as Anteros, the avenging spirit of his love. <ref>Pausanias I.30.1</ref><ref>Irina Kovaleva, "Eros at the Panathenaea: Personification of what?" in Emma Stafford, Judith Herrin, Personification in the Greek world: from antiquity to Byzantium. p.138</ref> | ||

*'''Polycrates and Smerdies''' | *'''Polycrates and Smerdies''' | ||

The love of the tyrant of Samos Island|Samos for his Thrace|Thracian favorite, some time between 535 BCE and 515 BCE, was recorded by the poet Anacreon.<ref>Aelian, ''Varia Historia,'' 9.4</ref> | ::The love of the tyrant of Samos Island|Samos for his Thrace|Thracian favorite, some time between 535 BCE and 515 BCE, was recorded by the poet Anacreon.<ref>Aelian, ''Varia Historia,'' 9.4</ref> | ||

*'''Polycrates and Bathyllus''' | *'''Polycrates and Bathyllus''' | ||

The tyrant dedicated a statue of his beloved in the temple of Hera in Samos. <ref>Apuleius, Flor. 215</ref> | ::The tyrant dedicated a statue of his beloved in the temple of Hera in Samos. <ref>Apuleius, Flor. 215</ref> | ||

*'''Anacreon and Bathyllus''' | *'''Anacreon and Bathyllus''' | ||

| Line 111: | Line 106: | ||

*'''Anacreon and Critias''' | *'''Anacreon and Critias''' | ||

Hipparchus invited Anacreon to Athens after the death of Polycrates. There Anacreon took an eromenos, in whose house he lived, and who, in a reversal of the usual roles, wrote love poetry to his erastes. It is not certain which Critias this is, though it has been proposed that it is the same as the eponymous archon.<ref>Louis Crompton, ''Homosexuality and Civilization;'' p.22</ref><ref>Debra Nails''The People of Plato: A Prosopography of Plato and Other Socratics'' p.107</ref> | ::Hipparchus invited Anacreon to Athens after the death of Polycrates. There Anacreon took an eromenos, in whose house he lived, and who, in a reversal of the usual roles, wrote love poetry to his erastes. It is not certain which Critias this is, though it has been proposed that it is the same as the eponymous archon.<ref>Louis Crompton, ''Homosexuality and Civilization;'' p.22</ref><ref>Debra Nails''The People of Plato: A Prosopography of Plato and Other Socratics'' p.107</ref> | ||

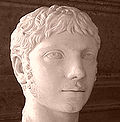

*'''[[Harmodius and Aristogeiton|Aristogeiton and Harmodius]]''' | *'''[[Harmodius and Aristogeiton|Aristogeiton and Harmodius]]''' | ||

Aristogeiton was a commoner from the middle classes, while Harmodius came from a noble Athenian family. Hipparchus, the son of the tyrant (or by Aristotle's account, a younger hotheaded brother of his, Thessalos) made an advance to Harmodius, who was already Aristogeiton's eromenos. The youth rejected his suitor, who in revenge denounced either Harmodius as malakos (effeminate, suggesting also sexual penetration) or his ostensibly virgin sister as dishonorable, leading to his sister's expulsion from a procession to which she had been summoned to carry the ceremonial basket. | ::Aristogeiton was a commoner from the middle classes, while Harmodius came from a noble Athenian family. Hipparchus, the son of the tyrant (or by Aristotle's account, a younger hotheaded brother of his, Thessalos) made an advance to Harmodius, who was already Aristogeiton's eromenos. The youth rejected his suitor, who in revenge denounced either Harmodius as malakos (effeminate, suggesting also sexual penetration) or his ostensibly virgin sister as dishonorable, leading to his sister's expulsion from a procession to which she had been summoned to carry the ceremonial basket. | ||

In order to avenge the insult to his family, Harmodius plotted with his erastes to assassinate the two brothers, Hippias and Hipparchus. Aristogeiton, wanting himself to avenge the attempted seduction of his eromenos, assented, and a plot was hatched that involved a number of other accomplices. Their plot misfired, and they only succeeded in assassinating Hippias' younger brother, Hipparchus. Harmodius lost his life in the attempt, while Aristogeiton died under torture a short while later. | ::In order to avenge the insult to his family, Harmodius plotted with his erastes to assassinate the two brothers, Hippias and Hipparchus. Aristogeiton, wanting himself to avenge the attempted seduction of his eromenos, assented, and a plot was hatched that involved a number of other accomplices. Their plot misfired, and they only succeeded in assassinating Hippias' younger brother, Hipparchus. Harmodius lost his life in the attempt, while Aristogeiton died under torture a short while later. | ||

The two were later lionized by the Athenian democrats, and their 514 BCE plot to assassinate Hippias was credited with the overthrow of tyranny in Athens. <ref>Richard Hunter, Ed. ''Plato's Symposium (Oxford Approaches to Classical Literature)'' p.52</ref> | ::The two were later lionized by the Athenian democrats, and their 514 BCE plot to assassinate Hippias was credited with the overthrow of tyranny in Athens. <ref>Richard Hunter, Ed. ''Plato's Symposium (Oxford Approaches to Classical Literature)'' p.52</ref> | ||

===Classical Greece=== | ===Classical Greece=== | ||

| Line 125: | Line 120: | ||

*'''Thorax and Hippocleas''' | *'''Thorax and Hippocleas''' | ||

Both lovers were Thessalian, the erastes a prince and his eromenos a young athlete who was the victor in the footrace at the Pythian games in 498. The boy's beauty was appreciated by both young and old, and among men as well as among women. <ref>"Relations of Measure" in "The Pindaric mind: a study of logical structure..." p22; Hubbard, 1985</ref> It was Thorax who commissioned Pindar's poem, the tenth Pythian Ode, in which the names of the two are immortalized.<ref>Thomas K. Hubbard, ''Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: a sourcebook of basic documents in translation'' Ch.1; p.85</ref> | ::Both lovers were Thessalian, the erastes a prince and his eromenos a young athlete who was the victor in the footrace at the Pythian games in 498. The boy's beauty was appreciated by both young and old, and among men as well as among women. <ref>"Relations of Measure" in "The Pindaric mind: a study of logical structure..." p22; Hubbard, 1985</ref> It was Thorax who commissioned Pindar's poem, the tenth Pythian Ode, in which the names of the two are immortalized.<ref>Thomas K. Hubbard, ''Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: a sourcebook of basic documents in translation'' Ch.1; p.85</ref> | ||

*'''Ilas and Hagesidamus''' | *'''Ilas and Hagesidamus''' | ||

Hagesidamus of Epizephyrian Locris was the adolescent victor at pankration on the occasion of the 76th Olympiad in 476. His trainer, Ilas, is thought to have also been his lover, based on the references and allusions in the poem which records their names and deeds: "Victorious as a boxer in the Olympics, let Hagesidamus give thanks to Ilas, just as Patroclus did to Achilles. A man aided by the arts of a god would whet one who is born to excellence and spur him toward awesome fame.<ref>"Pindar, 10th Olympian Ode</ref> Though some commentators have denied any erotic connotation to the relationship as described by Pindar, others consider that "The central reason for interpreting the Ilas-Hagesidamus relationship as not merely didactic is the application of Achilles and Patroclus as a mythological analogy.<ref>"Thomas K. Hubbard, "Sex in the gym: athletic trainers and pedagogical pederasty" in ''Intertexts'' 22-MAR-03 " [http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-3300526/Sex-in-the-gym-athletic.html]</ref> | ::Hagesidamus of Epizephyrian Locris was the adolescent victor at pankration on the occasion of the 76th Olympiad in 476. His trainer, Ilas, is thought to have also been his lover, based on the references and allusions in the poem which records their names and deeds: "Victorious as a boxer in the Olympics, let Hagesidamus give thanks to Ilas, just as Patroclus did to Achilles. A man aided by the arts of a god would whet one who is born to excellence and spur him toward awesome fame.<ref>"Pindar, 10th Olympian Ode</ref> Though some commentators have denied any erotic connotation to the relationship as described by Pindar, others consider that "The central reason for interpreting the Ilas-Hagesidamus relationship as not merely didactic is the application of Achilles and Patroclus as a mythological analogy.<ref>"Thomas K. Hubbard, "Sex in the gym: athletic trainers and pedagogical pederasty" in ''Intertexts'' 22-MAR-03 " [http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-3300526/Sex-in-the-gym-athletic.html]</ref> | ||

*'''Parmenides of Elea and Zeno of Elea''' | *'''Parmenides of Elea and Zeno of Elea''' | ||

According to Plato, Zeno was "tall and fair to look upon" and was "in the days of his youth . . . reported to have been beloved by Parmenides.<ref>"Plato, ''Parmenides,'' 127</ref> This would have occurred around 475 BCE. | ::According to Plato, Zeno was "tall and fair to look upon" and was "in the days of his youth . . . reported to have been beloved by Parmenides.<ref>"Plato, ''Parmenides,'' 127</ref> This would have occurred around 475 BCE. | ||

*'''Parmenides of Elea and Empedocles''' | *'''Parmenides of Elea and Empedocles''' | ||

The younger philosopher was first student and later the eromenos of Parmenides, according to Porphyry in his Philosophical History.<ref>''Suda,'' epsilon.1002</ref> | ::The younger philosopher was first student and later the eromenos of Parmenides, according to Porphyry in his Philosophical History.<ref>''Suda,'' epsilon.1002</ref> | ||

*'''Hiero I of Syracuse and Daelochus''' | *'''Hiero I of Syracuse and Daelochus''' | ||

Hiero, tyrant of Syracuse, surrounded himself with pederastic intellectuals and had a number of lovers. Around 470 BCE, on being challenged by Simonides on the ethics of being a pederast while a tyrant, he replied: ''"My passion for Daelochus arises from the fact that human nature perhaps compels us to want from the beautiful, but I have a very strong desire to attain the object of my passion [only] with his love and consent.''<ref>Xenophon, ''Hiero,'' I.31-38</ref> | ::Hiero, tyrant of Syracuse, surrounded himself with pederastic intellectuals and had a number of lovers. Around 470 BCE, on being challenged by Simonides on the ethics of being a pederast while a tyrant, he replied: ''"My passion for Daelochus arises from the fact that human nature perhaps compels us to want from the beautiful, but I have a very strong desire to attain the object of my passion [only] with his love and consent.''<ref>Xenophon, ''Hiero,'' I.31-38</ref> | ||

*'''Antileon and Hipparinos''' | *'''Antileon and Hipparinos''' | ||

Natives of Herakleia, in Lucania near Metapontum, the two were famed as tyrant killers in the style of Harmodius and Aristogiton. Antileon, scion of a notable family, fell in love with the handsome Hipparinos, a boy from a good family. The youth however despised his suitor. The latter, to prove his sincerity, declared himself willing to do anything for the boy's love. Hipparinos, to mock him, told him to fetch a precious goblet securely kept inside the fortress that was occupied by the tyrant of Herakleia and his soldiers. Antileon scaled the ramparts, killed the guards and brought back the goblet, thus winning the boy's love. | ::Natives of Herakleia, in Lucania near Metapontum, the two were famed as tyrant killers in the style of Harmodius and Aristogiton. Antileon, scion of a notable family, fell in love with the handsome Hipparinos, a boy from a good family. The youth however despised his suitor. The latter, to prove his sincerity, declared himself willing to do anything for the boy's love. Hipparinos, to mock him, told him to fetch a precious goblet securely kept inside the fortress that was occupied by the tyrant of Herakleia and his soldiers. Antileon scaled the ramparts, killed the guards and brought back the goblet, thus winning the boy's love. | ||

Soon thereafter the tyrant of Herakleia himself fell for the boy. Antileon advised his eromenos to feign acceptance and to invite the tyrant, but when the tyrnat arrived at the house Antileon sprang on him and killed him, thus liberating the city. Antileon paid with his life, but later his compatriots raised bronze statues to him and his beloved.<ref> Phanias of Eresus, Fr. 16 FHGEd.</ref> <ref>Thomas K. Hubbard, ''Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents,'' p. 62 [http://www.laits.utexas.edu/ancienthomosexuality/readindex.php?view=17] [after Parthenius, in Meier, HistAmGr, 166-167]</ref> | ::Soon thereafter the tyrant of Herakleia himself fell for the boy. Antileon advised his eromenos to feign acceptance and to invite the tyrant, but when the tyrnat arrived at the house Antileon sprang on him and killed him, thus liberating the city. Antileon paid with his life, but later his compatriots raised bronze statues to him and his beloved.<ref> Phanias of Eresus, Fr. 16 FHGEd.</ref> <ref>Thomas K. Hubbard, ''Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents,'' p. 62 [http://www.laits.utexas.edu/ancienthomosexuality/readindex.php?view=17] [after Parthenius, in Meier, HistAmGr, 166-167]</ref> | ||

*'''Pausanias (general) and Argilius''' | *'''Pausanias (general) and Argilius''' | ||

The general was sending treasonous letters to the Persians by means of his former lovers, none of whom ever returned. Argilius, upon being appointed messenger, in 470, opened the letter in secret, only to find out that it instructed the receiver of the letter to kill its bearer. He divulged Pausanias correspondence to the ephors, who had Pausanias walled up within the temple where he had taken refuge, starving him to death for communicating with the enemy.<ref>Thucydides, I, 132, 1-5A</ref> <ref>Christian's guide to Greek culture By Gregory of Nazianus, Gregory, Pseudo-Nonnos, Jennifer Nimmo Smith; p.100</ref> | ::The general was sending treasonous letters to the Persians by means of his former lovers, none of whom ever returned. Argilius, upon being appointed messenger, in 470, opened the letter in secret, only to find out that it instructed the receiver of the letter to kill its bearer. He divulged Pausanias correspondence to the ephors, who had Pausanias walled up within the temple where he had taken refuge, starving him to death for communicating with the enemy.<ref>Thucydides, I, 132, 1-5A</ref> <ref>Christian's guide to Greek culture By Gregory of Nazianus, Gregory, Pseudo-Nonnos, Jennifer Nimmo Smith; p.100</ref> | ||

*'''Archelaus and Socrates''' | *'''Archelaus and Socrates''' | ||

The older philosopher loved the younger when the latter was seventeen, for "at the time he was much given to sensuality."<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=0o0VAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover Hans Licht, ''Sexual life in ancient Greece'' Panther History; p.400;]</ref><ref>Diogenes Laërtius, ii.</ref><ref>Porphyrius</ref><ref>Aristoxenus of Tarentum</ref> | ::The older philosopher loved the younger when the latter was seventeen, for "at the time he was much given to sensuality."<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=0o0VAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover Hans Licht, ''Sexual life in ancient Greece'' Panther History; p.400;]</ref><ref>Diogenes Laërtius, ii.</ref><ref>Porphyrius</ref><ref>Aristoxenus of Tarentum</ref> | ||

*'''Sophocles and Demophon''' | *'''Sophocles and Demophon''' | ||

According to a satirical account by Machon, involving a hetaira known for her ironical sense of humor, "Demophon, Sophocles' minion, when still a youth had Nico, already old and surnamed the she-goat; they say she had very fine buttocks. One day he begged of her to lend them to him. 'Very well,' she said with a smile,—'Take from me, dear, what you give to Sophocles.'"<ref>Friederich Karl Forberg, ''Manual of Classical Erotology (De Figuris Veneris)''; p.74 N26</ref><ref>Lee Alexander Stone, ''The Power of a Symbol'', p.229</ref> | ::According to a satirical account by Machon, involving a hetaira known for her ironical sense of humor, "Demophon, Sophocles' minion, when still a youth had Nico, already old and surnamed the she-goat; they say she had very fine buttocks. One day he begged of her to lend them to him. 'Very well,' she said with a smile,—'Take from me, dear, what you give to Sophocles.'"<ref>Friederich Karl Forberg, ''Manual of Classical Erotology (De Figuris Veneris)''; p.74 N26</ref><ref>Lee Alexander Stone, ''The Power of a Symbol'', p.229</ref> | ||

*'''Phidias and Agoracritus''' | *'''Phidias and Agoracritus''' | ||

The youth, both beloved and student of the sculptor, is also known for his sculpture of Nemesis at Rhamnus. <ref>Pausanias, IX.34.1 "In the temple are bronze images of Itonian Athena and Zeus; the artist was Agoracritus, pupil and loved one of Pheidias." ''(...technê de Agorakritou, mathêtou te kai erômenou Pheidiou.)''</ref> | ::The youth, both beloved and student of the sculptor, is also known for his sculpture of Nemesis at Rhamnus. <ref>Pausanias, IX.34.1 "In the temple are bronze images of Itonian Athena and Zeus; the artist was Agoracritus, pupil and loved one of Pheidias." ''(...technê de Agorakritou, mathêtou te kai erômenou Pheidiou.)''</ref> | ||

*'''Pindar and Theoxenus''' | *'''Pindar and Theoxenus''' | ||

Thought by some to have been his eromenos, Theoxenus is the subject of a skolion in which Pindar praises the love of boys and his own vulnerability to their beauty. According to one account, Pindar died, at the age of eighty, at the theater in Argos, leaning upon the boy's shoulder.<ref>Louis Crompton, ''Homosexuality and Civilization'' p.50</ref> | ::Thought by some to have been his eromenos, Theoxenus is the subject of a skolion in which Pindar praises the love of boys and his own vulnerability to their beauty. According to one account, Pindar died, at the age of eighty, at the theater in Argos, leaning upon the boy's shoulder.<ref>Louis Crompton, ''Homosexuality and Civilization'' p.50</ref> | ||

*'''Phidias and Pantarkes''' | *'''Phidias and Pantarkes''' | ||

Pantarkes, was an Elian youth and winner of the boys' wrestling match at the 86th Ancient Olympics in 436 BCE. He modeled for one of the figures sculpted in the throne of the Olympian Zeus, and Phidias, to honor him, carved "Kalos Pantarkes" into the god's little finger.<ref>Plutarch, ''Erotikos;</ref><ref>''Pausanias, V.11.3. "The figure of one binding his own head with a ribbon is said to resemble in appearance Pantarces, a stripling of Elis said to have been the love of Pheidias. Pantarces too won the wrestling-bout for boys at the eighty-sixth Festival." ''(ton de hauton tainiai tên kephalên anadoumenon eoikenai to eidos Pantarkei legousi, meirakion de Êleion ton Pantarkê paidika einai tou Pheidiou: aneileto de kai en paisin ho Pantarkês palês nikên Olumpiadi hektêi pros tais ogdoêkonta.)''</ref><ref>Clement of Alexandria, ''Protrepticus'', 53, 4; "The Athenian Phidias inscribed on the finger of the Olympian Jove, Pantarkes is beautiful. It was not Zeus that was beautiful in his eyes, but the man he loved."</ref> A statue of his stood at Olympia, with those of the other victors.<ref>"After Iccus stands Pantarces the Elean, beloved of Pheidias, who beat the boys at wrestling." Pausanias, 6.10.6</ref> | ::Pantarkes, was an Elian youth and winner of the boys' wrestling match at the 86th Ancient Olympics in 436 BCE. He modeled for one of the figures sculpted in the throne of the Olympian Zeus, and Phidias, to honor him, carved "Kalos Pantarkes" into the god's little finger.<ref>Plutarch, ''Erotikos;</ref><ref>''Pausanias, V.11.3. "The figure of one binding his own head with a ribbon is said to resemble in appearance Pantarces, a stripling of Elis said to have been the love of Pheidias. Pantarces too won the wrestling-bout for boys at the eighty-sixth Festival." ''(ton de hauton tainiai tên kephalên anadoumenon eoikenai to eidos Pantarkei legousi, meirakion de Êleion ton Pantarkê paidika einai tou Pheidiou: aneileto de kai en paisin ho Pantarkês palês nikên Olumpiadi hektêi pros tais ogdoêkonta.)''</ref><ref>Clement of Alexandria, ''Protrepticus'', 53, 4; "The Athenian Phidias inscribed on the finger of the Olympian Jove, Pantarkes is beautiful. It was not Zeus that was beautiful in his eyes, but the man he loved."</ref> A statue of his stood at Olympia, with those of the other victors.<ref>"After Iccus stands Pantarces the Elean, beloved of Pheidias, who beat the boys at wrestling." Pausanias, 6.10.6</ref> | ||

*'''Empedocles and Pausanias of Sicily''' | *'''Empedocles and Pausanias of Sicily''' | ||

Pausanias was both friend and student of the philosopher, according to Aristippus and Satyrus. He addressed his poem "On Nature" to him, with the words, "And Pausanias, son of wise Anchites, you listen!" And he also wrote an epigram for him, "Pausanias, the doctor, named for his craft, son of Anchites, a man of Asclepias' lineage, was reared in Gela, his homeland. He turned many men who were wasting with painful illness away from the halls of Persephone.<ref>Diogenes Laertius, ''Lives of the Philosophers'' "Life of Empedocles" Jonathan Barne, ''Early Greek Philosophy'' p.113</ref> | ::Pausanias was both friend and student of the philosopher, according to Aristippus and Satyrus. He addressed his poem "On Nature" to him, with the words, "And Pausanias, son of wise Anchites, you listen!" And he also wrote an epigram for him, "Pausanias, the doctor, named for his craft, son of Anchites, a man of Asclepias' lineage, was reared in Gela, his homeland. He turned many men who were wasting with painful illness away from the halls of Persephone.<ref>Diogenes Laertius, ''Lives of the Philosophers'' "Life of Empedocles" Jonathan Barne, ''Early Greek Philosophy'' p.113</ref> | ||

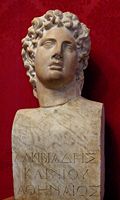

[[Image:Bust Alcibiades Musei Capitolini MC1160.jpg|thumb|120px|[[Alcibiades]]]] | [[Image:Bust Alcibiades Musei Capitolini MC1160.jpg|thumb|120px|[[Alcibiades]]]] | ||

*'''Autolykos and [[Alcibiades]]''' | *'''Autolykos and [[Alcibiades]]''' | ||

According to one tradition, while still a ward of Pericles and living in his house, Alcibiades took up with Democrates, causing Pericles to almost throw him out of the house. <ref>Household interests By Cheryl Anne Cox; p.145</ref> | ::According to one tradition, while still a ward of Pericles and living in his house, Alcibiades took up with Democrates, causing Pericles to almost throw him out of the house. <ref>Household interests By Cheryl Anne Cox; p.145</ref> | ||

*'''Anytus and [[Alcibiades]]''' | *'''Anytus and [[Alcibiades]]''' | ||

Anytus was one of the lovers whom Alcibides grew to despise. Anytus defended the young Alcibiades to his guests on the occasion of a symposium during which the boy entered the room only to make off with half the cups on the table. Rather than agreeing with the guests who accused Alcibides of insolence and contempt, Anytus claimed the boy did him a kindness, since he could just as easily have walked off with all the cups.<ref>Plutarch, ''Amatorius'' 17 (''Moralia'').</ref> | ::Anytus was one of the lovers whom Alcibides grew to despise. Anytus defended the young Alcibiades to his guests on the occasion of a symposium during which the boy entered the room only to make off with half the cups on the table. Rather than agreeing with the guests who accused Alcibides of insolence and contempt, Anytus claimed the boy did him a kindness, since he could just as easily have walked off with all the cups.<ref>Plutarch, ''Amatorius'' 17 (''Moralia'').</ref> | ||

*'''Axiochus and [[Alcibiades]]''' | *'''Axiochus and [[Alcibiades]]''' | ||

Lysias, in one of his speeches, denounced Alcibiades for having sailed to Abydus with his uncle, Axiochus, who was both erastes and fellow in the debaucheries to which the two lent themselves, once arrived at their destination.<ref>Alcibiades and Athens By David Gribble, p.75</ref> | ::Lysias, in one of his speeches, denounced Alcibiades for having sailed to Abydus with his uncle, Axiochus, who was both erastes and fellow in the debaucheries to which the two lent themselves, once arrived at their destination.<ref>Alcibiades and Athens By David Gribble, p.75</ref> | ||

*'''Socrates and [[Alcibiades]]''' | *'''Socrates and [[Alcibiades]]''' | ||

Each is said to have saved the life of the other in battle, and the relationship, which may have begun around 435-430 was said to have been chaste. Alcibiades ceased being Socrates' eromenos around 420, when he went into politics, according to Xenophon <ref>Mem. 1.1.24</ref> <ref>Robert J. Littman, "The Loves of Alcibiades" in ''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association,'' Vol. 101, 1970 (1970), pp. 263-276 "Socrates' and Alcibiades' relationship is very much connected to the role of pederasty in education in classical Greece..."</ref> In adulthood Alcibiades tastes changed, leading Bion to comment that as a boy Alcibides caused all men to be unfaithful to their wives, and as a young man he caused all women to be unfaithful to their husbands. | ::Each is said to have saved the life of the other in battle, and the relationship, which may have begun around 435-430 was said to have been chaste. Alcibiades ceased being Socrates' eromenos around 420, when he went into politics, according to Xenophon <ref>Mem. 1.1.24</ref> <ref>Robert J. Littman, "The Loves of Alcibiades" in ''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association,'' Vol. 101, 1970 (1970), pp. 263-276 "Socrates' and Alcibiades' relationship is very much connected to the role of pederasty in education in classical Greece..."</ref> In adulthood Alcibiades tastes changed, leading Bion to comment that as a boy Alcibides caused all men to be unfaithful to their wives, and as a young man he caused all women to be unfaithful to their husbands. | ||

*'''Herodotus and Plesirrhous the Thessalian''' | *'''Herodotus and Plesirrhous the Thessalian''' | ||

According to Ptolemy Hephaestion, also known as Ptolemaeus Chennus, epitomized in the Library of Photius, "Plesirrhous the Thessalian, author of hymns, was taken by Herodotus as eromenos, and also appointed as his heir; it is he who composed the introduction of the first book of Herodotus of Halicarnassus." | ::According to Ptolemy Hephaestion, also known as Ptolemaeus Chennus, epitomized in the Library of Photius, "Plesirrhous the Thessalian, author of hymns, was taken by Herodotus as eromenos, and also appointed as his heir; it is he who composed the introduction of the first book of Herodotus of Halicarnassus." | ||

Not satisfied with a good anecdote, Ptolemy then goes on to tell another story about this eromenos which conflicts with the first: now Plesirrhous dies while his erastes is still busy writing his Histories. According to Ptolemaeus, in that work Herodotus does not mention the name of Candaulus' wife because of the pain it brings him: "The wife's name was, it is said, passed over in silence by Herodotus because Plesirrhous, whom Herodotus loved, was taken with a woman called Nysia and who was of a family of Halicarnassus, and that he hanged himself when he was unsuccessful with her. It is for this reason that Herodotus does not mention the name of Nysia which was odious to him.<ref>"Καὶ ὡς Πλησίρροος ὁ Θεσσαλὸς ὁ ὑμνογράφος, ἐρώμενος γεγονὼς Ἡροδότου καὶ κληρονόμος τῶν αὐτοῦ" Photius, ''Library;'' "Ptolemy Chennus, New History" 190.</ref> | ::Not satisfied with a good anecdote, Ptolemy then goes on to tell another story about this eromenos which conflicts with the first: now Plesirrhous dies while his erastes is still busy writing his Histories. According to Ptolemaeus, in that work Herodotus does not mention the name of Candaulus' wife because of the pain it brings him: "The wife's name was, it is said, passed over in silence by Herodotus because Plesirrhous, whom Herodotus loved, was taken with a woman called Nysia and who was of a family of Halicarnassus, and that he hanged himself when he was unsuccessful with her. It is for this reason that Herodotus does not mention the name of Nysia which was odious to him.<ref>"Καὶ ὡς Πλησίρροος ὁ Θεσσαλὸς ὁ ὑμνογράφος, ἐρώμενος γεγονὼς Ἡροδότου καὶ κληρονόμος τῶν αὐτοῦ" Photius, ''Library;'' "Ptolemy Chennus, New History" 190.</ref> | ||

These two conflicting stories may say more about the literary taste of the age in which they were written than about Herodotus himself. Though some have categorized these anecdotes as "deceitful philology," other historians have given credence to the account of Plessirhous as eromenos and heir, about as much credence as they give all of Herodotus' works.<ref> A Life of Aristotle, Including a Critical Discussion of Some Questions of ... By Joseph Williams Blakesley, p.26 .</ref><ref>A commentary on Herodotus books I-IV By David Asheri, Alan Lloyd, Aldo Corcella, Oswyn Murray, Alfonso Moreno, Barbara Graziosi, p.1; Phot.Bibliothec.Cod.190, p478 as cited by George Rawlinson, The History of Herodotus Vol.I, D.Appleton and Co., New York (1859), page 27</ref> | ::These two conflicting stories may say more about the literary taste of the age in which they were written than about Herodotus himself. Though some have categorized these anecdotes as "deceitful philology," other historians have given credence to the account of Plessirhous as eromenos and heir, about as much credence as they give all of Herodotus' works.<ref> A Life of Aristotle, Including a Critical Discussion of Some Questions of ... By Joseph Williams Blakesley, p.26 .</ref><ref>A commentary on Herodotus books I-IV By David Asheri, Alan Lloyd, Aldo Corcella, Oswyn Murray, Alfonso Moreno, Barbara Graziosi, p.1; Phot.Bibliothec.Cod.190, p478 as cited by George Rawlinson, The History of Herodotus Vol.I, D.Appleton and Co., New York (1859), page 27</ref> | ||

*'''Callicles and Demus''' | *'''Callicles and Demus''' | ||

According to Plato's dialog, Callicles love for the beautiful son of Pyrilampes, of whom graffiti declaring ''Demus is beautiful'' ''(Demon kalon)'' were scribbled through the city in the 420s, <ref>Aristophanes, ''Wasps,'' 95-100</ref> paralleled Callicles' love for the Athenian ''demos,'' or populace. <ref>Plato, ''Gorgias'' (483b - 484c). The first instance of his being mentioned as available (kalos) is in 422. (Ar. Vesp. 97)</ref> | ::According to Plato's dialog, Callicles love for the beautiful son of Pyrilampes, of whom graffiti declaring ''Demus is beautiful'' ''(Demon kalon)'' were scribbled through the city in the 420s, <ref>Aristophanes, ''Wasps,'' 95-100</ref> paralleled Callicles' love for the Athenian ''demos,'' or populace. <ref>Plato, ''Gorgias'' (483b - 484c). The first instance of his being mentioned as available (kalos) is in 422. (Ar. Vesp. 97)</ref> | ||

*'''Critias and Euthydemus''' | *'''Critias and Euthydemus''' | ||

Failing to dissuade Critias from importuning his eromenos Euthydemus to engage in dishonorable sex, Socrates publicly berated the crude physicality of Critias' desire by publicly comparing him to a piglet wanting to scratch himself against a rock, provoking a permanent break between himself and the future tyrant.<ref>Sophists, Socratics, and Cynics By H. D. Rankin, p.71; Barnes and Noble, Totowa, 1983</ref> Xenophon also mentions the two and supports Socrates´view.<ref>C. Hindley, "Sophron Eros: Xenophon´s Ethical Erotics" in ''Xenophon and His World'' By Christopher Tuplin, Vincent Azoulay, pp125-126; Published by Franz Steiner Verlag, 2004</ref> | ::Failing to dissuade Critias from importuning his eromenos Euthydemus to engage in dishonorable sex, Socrates publicly berated the crude physicality of Critias' desire by publicly comparing him to a piglet wanting to scratch himself against a rock, provoking a permanent break between himself and the future tyrant.<ref>Sophists, Socratics, and Cynics By H. D. Rankin, p.71; Barnes and Noble, Totowa, 1983</ref> Xenophon also mentions the two and supports Socrates´view.<ref>C. Hindley, "Sophron Eros: Xenophon´s Ethical Erotics" in ''Xenophon and His World'' By Christopher Tuplin, Vincent Azoulay, pp125-126; Published by Franz Steiner Verlag, 2004</ref> | ||

*'''Critias and Glaucon''' | *'''Critias and Glaucon''' | ||

Glaucon, the older brother of Plato, had his uncle, Critias, for an erastes. Later he chased after eromenoi of his own, for which he is teased in The Republic.<ref>Republic 474d-eThe people of Plato: a prosopography of Plato and other Socratics By Debra Nails; pp 108, 155</ref> | ::Glaucon, the older brother of Plato, had his uncle, Critias, for an erastes. Later he chased after eromenoi of his own, for which he is teased in The Republic.<ref>Republic 474d-eThe people of Plato: a prosopography of Plato and other Socratics By Debra Nails; pp 108, 155</ref> | ||

*'''Pausanias and Agathon''' | *'''Pausanias and Agathon''' | ||

Originally erastes and eromenos, the two were renowned for having remained in a love relationship for ten years, long past the time when it should have ended, according to custom.<ref>Naked Truths By Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, Claire L. Lyons, N51; p.147[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plat.+Prot.+315e Plato, ''Protagoras'' 315e]</ref> | ::Originally erastes and eromenos, the two were renowned for having remained in a love relationship for ten years, long past the time when it should have ended, according to custom.<ref>Naked Truths By Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, Claire L. Lyons, N51; p.147[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plat.+Prot.+315e Plato, ''Protagoras'' 315e]</ref> | ||

*'''Plato and Aster''' | *'''Plato and Aster''' | ||

Diogenes Laertius, in a biographical sketch, mentions Plato´s "passionate affection" for males and cites as evidence five of his poems. One of his beloveds is said to have been a certain Aster, to whom he was teaching astronomy. That reading has also been supported by such modern figures as Percy Bysshe Shelley, Edward Carpenter,Edward Carpenter, ''Iolaus'', p.78; Cosimo, New York. 2005 and others. | ::Diogenes Laertius, in a biographical sketch, mentions Plato´s "passionate affection" for males and cites as evidence five of his poems. One of his beloveds is said to have been a certain Aster, to whom he was teaching astronomy. That reading has also been supported by such modern figures as Percy Bysshe Shelley, Edward Carpenter,Edward Carpenter, ''Iolaus'', p.78; Cosimo, New York. 2005 and others. | ||

::My Aster, you're gazing on the stars, | ::My Aster, you're gazing on the stars, | ||

| Line 226: | Line 221: | ||

::Gaze in return with many eyes on thee.<ref>''Homosexuality & Civilization'' by Louis Crompton p.55</ref><ref>"There seems to be no serious objection to the view that in his youth Plato wrote the two epigrams on Aster." ''Plato's Epigram on Dion's Death'', C. M. Bowra, The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 59, No. 4 (1938), pp. 394-404</ref><ref>Diogenes Laertius, ''THE LIVES AND OPINIONS OF EMINENT PHILOSOPHERS'' Plato, XXIII</ref> | ::Gaze in return with many eyes on thee.<ref>''Homosexuality & Civilization'' by Louis Crompton p.55</ref><ref>"There seems to be no serious objection to the view that in his youth Plato wrote the two epigrams on Aster." ''Plato's Epigram on Dion's Death'', C. M. Bowra, The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 59, No. 4 (1938), pp. 394-404</ref><ref>Diogenes Laertius, ''THE LIVES AND OPINIONS OF EMINENT PHILOSOPHERS'' Plato, XXIII</ref> | ||

Shelley, acting on his reading of the poem as an amorous reference that would be unacceptable to contemporary audiences, bowdlerized the name of the youth from Aster to Stella, to obscure the poet´s love for a boy.<ref>John Lauritsen, [http://paganpressbooks.com/jpl/HHREV3.HTM "Hellenism and Homoeroticism in Shelley and his Circle"] in ''Same-sex desire and love in Greco-Roman antiquity'', Ed. Beert C. Verstraete, Vernon Provencal, p.364</ref> | ::Shelley, acting on his reading of the poem as an amorous reference that would be unacceptable to contemporary audiences, bowdlerized the name of the youth from Aster to Stella, to obscure the poet´s love for a boy.<ref>John Lauritsen, [http://paganpressbooks.com/jpl/HHREV3.HTM "Hellenism and Homoeroticism in Shelley and his Circle"] in ''Same-sex desire and love in Greco-Roman antiquity'', Ed. Beert C. Verstraete, Vernon Provencal, p.364</ref> | ||

*'''Xenophon and Clinias''' | *'''Xenophon and Clinias''' | ||

Of his eromenos, Xenophon said, "Now I look upon Clinias with more pleasure than upon all the other beautiful things which are to be seen among men; and I would rather be blind as to all the rest of the world, than as to Clinias. And I am annoyed even with night and with sleep, because then I do not see him; but I am very grateful to the sun and to daylight, because they show Clinias to me.<ref>"Diogenes Laertius, ''LIFE OF XENOPHON''</ref> They are one of the couples mentioned by Giovanni Pico della Mirandola in his comment to his friend Girolamo Benivieni's ''Dell' amore celesto e divino,'' where he asserts of them that they "did not wish to perform with their beloved ones any filthy actions (as believed by many people who judge the heavenly thoughts of those philosophers with the measure of their shameful desires), but only to get incitement from the body's outward beauty to look at that of the soul, from which proceeded and came the bodily one.<ref>"The Pursuit of sodomy By Kent Gerard, Gert Hekma; p44</ref><ref> Though in the SYmposium, Xenophon makes out Critobulus to be the lover of Cleinias, Diogenes Laertius, quoting Aristippus, claims that it was Xenophon himself who was in love with Cleinias. ''The Socratic movement'' By Paul A. Vander Waerdt: p221N8</ref> | ::Of his eromenos, Xenophon said, "Now I look upon Clinias with more pleasure than upon all the other beautiful things which are to be seen among men; and I would rather be blind as to all the rest of the world, than as to Clinias. And I am annoyed even with night and with sleep, because then I do not see him; but I am very grateful to the sun and to daylight, because they show Clinias to me.<ref>"Diogenes Laertius, ''LIFE OF XENOPHON''</ref> They are one of the couples mentioned by Giovanni Pico della Mirandola in his comment to his friend Girolamo Benivieni's ''Dell' amore celesto e divino,'' where he asserts of them that they "did not wish to perform with their beloved ones any filthy actions (as believed by many people who judge the heavenly thoughts of those philosophers with the measure of their shameful desires), but only to get incitement from the body's outward beauty to look at that of the soul, from which proceeded and came the bodily one.<ref>"The Pursuit of sodomy By Kent Gerard, Gert Hekma; p44</ref><ref> Though in the SYmposium, Xenophon makes out Critobulus to be the lover of Cleinias, Diogenes Laertius, quoting Aristippus, claims that it was Xenophon himself who was in love with Cleinias. ''The Socratic movement'' By Paul A. Vander Waerdt: p221N8</ref> | ||

*'''Lysander and Agesilaus II''' | *'''Lysander and Agesilaus II''' | ||

In the late 430s Lysander had been the ''eispnelas'' of Agesilaus, taking the youth on despite his lameness and was instrumental in the latter's rise to kingship only to be spurned by him once he rose to power in 399 BCE. <ref>Paul Cartledge, ''Spartan Reflections,'' p.104</ref> | ::In the late 430s Lysander had been the ''eispnelas'' of Agesilaus, taking the youth on despite his lameness and was instrumental in the latter's rise to kingship only to be spurned by him once he rose to power in 399 BCE. <ref>Paul Cartledge, ''Spartan Reflections,'' p.104</ref> | ||

*'''Callias III and Autolycus''' | *'''Callias III and Autolycus''' | ||

The relationship between the two, in 421 BCE, is touched upon in Xenophon's ''Symposium'', where Callias entertains both the boy and the father, Lykon of the deme Thorikos. The previous year Autolycus had won the boys' pankration (a kind of boxing) at the Panathenaic Games. <ref>Xenophon, ''Symposium''</ref> Later in the same work we meet Callias as erastes again, when Socrates exhorts him to put his extremely erotic nature to good use by channeling its energy into politics in order to please, above all, his eromenos. <ref>Autolycus was put to death by the Thirty in 404. The Shorter Socratic Writings By Xenophon, Robert C. Bartlett; p.180</ref> | ::The relationship between the two, in 421 BCE, is touched upon in Xenophon's ''Symposium'', where Callias entertains both the boy and the father, Lykon of the deme Thorikos. The previous year Autolycus had won the boys' pankration (a kind of boxing) at the Panathenaic Games. <ref>Xenophon, ''Symposium''</ref> Later in the same work we meet Callias as erastes again, when Socrates exhorts him to put his extremely erotic nature to good use by channeling its energy into politics in order to please, above all, his eromenos. <ref>Autolycus was put to death by the Thirty in 404. The Shorter Socratic Writings By Xenophon, Robert C. Bartlett; p.180</ref> | ||

*'''Themistocles and Stesilaus of Ceos''' | *'''Themistocles and Stesilaus of Ceos''' | ||

Around 420 BCE Themistocles competed for the boy's love with Aristides. As Plutarch recounts, "... they were rivals for the affection of the beautiful Stesilaus of Ceos, and were passionate beyond all moderation.<ref>"''Plutarch, ''The Lives,'' "Themistocles"</ref> | ::Around 420 BCE Themistocles competed for the boy's love with Aristides. As Plutarch recounts, "... they were rivals for the affection of the beautiful Stesilaus of Ceos, and were passionate beyond all moderation.<ref>"''Plutarch, ''The Lives,'' "Themistocles"</ref> | ||

*'''Pytheas and Teisis''' | *'''Pytheas and Teisis''' | ||

Pytheas, who was also the guardian of the youth, appointed to that position by Teisis' father in his will, is held up as being an unwise erastes, concerned with impressing his eromenos and as a result giving him bad advice.<ref>Lysias, ''Against Teisis'', Fr.17.2.1-2, in Hubbard, 2003, p.122</ref> | ::Pytheas, who was also the guardian of the youth, appointed to that position by Teisis' father in his will, is held up as being an unwise erastes, concerned with impressing his eromenos and as a result giving him bad advice.<ref>Lysias, ''Against Teisis'', Fr.17.2.1-2, in Hubbard, 2003, p.122</ref> | ||

*'''Archedemus and Alcibiades the Younger''' | *'''Archedemus and Alcibiades the Younger''' | ||

In his childhood, Alcibiades the Younger, son of the famous general by the same name, was notorious for frequenting the house of his erastes, drinking, and reclining with him under a single cloak in sight of all.<ref name="Lysias, 2003, pp.122-23">Lysias, ''Against Alcibiades,'' I 25-27 in Hubbard, 2003, pp.122-23; Young Alcibiades also took other lovers, among whom Theotimus and Critobulus, son of Criton. [Meier, HistAmGr, 94</ref> | ::In his childhood, Alcibiades the Younger, son of the famous general by the same name, was notorious for frequenting the house of his erastes, drinking, and reclining with him under a single cloak in sight of all.<ref name="Lysias, 2003, pp.122-23">Lysias, ''Against Alcibiades,'' I 25-27 in Hubbard, 2003, pp.122-23; Young Alcibiades also took other lovers, among whom Theotimus and Critobulus, son of Criton. [Meier, HistAmGr, 94</ref> | ||

*'''Archebiades and Alcibiades the Younger''' | *'''Archebiades and Alcibiades the Younger''' | ||

After the death of the older Alcibiades, his old associate and co-defendant in the desecration of the Eleusinian mysteries, became the erastes of his son, then in his early teens, ransoming him from imprisonment, a ransom the boy's father had refused to pay, out of disgust with his own son.<ref name="Lysias, 2003, pp.122-23"/> | ::After the death of the older Alcibiades, his old associate and co-defendant in the desecration of the Eleusinian mysteries, became the erastes of his son, then in his early teens, ransoming him from imprisonment, a ransom the boy's father had refused to pay, out of disgust with his own son.<ref name="Lysias, 2003, pp.122-23"/> | ||

*'''Archidamus and Cleonymus''' | *'''Archidamus and Cleonymus''' | ||

Archidamus, son of Agesilaus II, is described by Xenophon to have been in love with the handsome son of Sphodrias. The boy asked his ''eispnelas'' to intervene with the king in favor of his father in a life and death legal matter, promising that Archidamus would never be ashamed to have befriended him. That proved to be so, as he was the first Spartan to die at the battle of Leuctra.<ref>Xenophon, ''Hellenica'' 5.4 The relationship lasted from 378 to 371. (Xenophon and his world: papers from a conference held in Liverpool in July 1999 By Christopher Tuplin, Vincent Azoulay; p.127)</ref> | ::Archidamus, son of Agesilaus II, is described by Xenophon to have been in love with the handsome son of Sphodrias. The boy asked his ''eispnelas'' to intervene with the king in favor of his father in a life and death legal matter, promising that Archidamus would never be ashamed to have befriended him. That proved to be so, as he was the first Spartan to die at the battle of Leuctra.<ref>Xenophon, ''Hellenica'' 5.4 The relationship lasted from 378 to 371. (Xenophon and his world: papers from a conference held in Liverpool in July 1999 By Christopher Tuplin, Vincent Azoulay; p.127)</ref> | ||

*'''Aristippus of Larissa and Menon III of Pharsalus''' | *'''Aristippus of Larissa and Menon III of Pharsalus''' | ||

Thessalians. Meno, the Socratic dialogue is named after Menon. Menon's lover raised 1000 hoplites and 500 peltasts <ref>The Greek Wars: The Failure of Persia By George Cawkwell; p160</ref> to aid Cyrus the Younger, set his beloved as their general, and sent the youth on the expedition into Persia in his stead. <ref>Greek homosexuality By Kenneth James Dover, p.154</ref><ref>Anabasis By Xenophon, p.13 N3; Tr. H. G. Dakyns; BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008</ref> | ::Thessalians. Meno, the Socratic dialogue is named after Menon. Menon's lover raised 1000 hoplites and 500 peltasts <ref>The Greek Wars: The Failure of Persia By George Cawkwell; p160</ref> to aid Cyrus the Younger, set his beloved as their general, and sent the youth on the expedition into [[Persian Empire|Persia]] in his stead. <ref>Greek homosexuality By Kenneth James Dover, p.154</ref><ref>Anabasis By Xenophon, p.13 N3; Tr. H. G. Dakyns; BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008</ref> | ||

*'''Ariaeus and Menon III of Pharsalus''' | *'''Ariaeus and Menon III of Pharsalus''' | ||

Menon, a commander of Greek mercenaries in Cyrus the Younger's army who had received his commission on account of his youthful beauty, took Ariaeus, the Persian general, as his lover. The matter was badly seen, as it was deemed especially base to submit sexually to a barbarian.<ref name="Xenophon, Anabasis; 2.6.29">Xenophon, ''Anabasis;'' 2.6.29</ref><ref name="Robin Lane Fox p.198">Robin Lane Fox, ''The Long March: Xenophon and the Ten Thousand'' p.198</ref> | ::Menon, a commander of Greek mercenaries in Cyrus the Younger's army who had received his commission on account of his youthful beauty, took Ariaeus, the Persian general, as his lover. The matter was badly seen, as it was deemed especially base to submit sexually to a barbarian.<ref name="Xenophon, Anabasis; 2.6.29">Xenophon, ''Anabasis;'' 2.6.29</ref><ref name="Robin Lane Fox p.198">Robin Lane Fox, ''The Long March: Xenophon and the Ten Thousand'' p.198</ref> | ||

*'''Menon III of Pharsalus and Tharypas''' | *'''Menon III of Pharsalus and Tharypas''' | ||

In a reversal of the usual custom, Menon, a commander of a troop of mercenaries despite his adolescence, still beardless and in his ''hora'',Figures of speech By Gloria Ferrari; p.140 took as "beloved" the bearded Tharypas.<ref name="Xenophon, Anabasis; 2.6.29"/><ref name="Robin Lane Fox p.198"/> | ::In a reversal of the usual custom, Menon, a commander of a troop of mercenaries despite his adolescence, still beardless and in his ''hora'',Figures of speech By Gloria Ferrari; p.140 took as "beloved" the bearded Tharypas.<ref name="Xenophon, Anabasis; 2.6.29"/><ref name="Robin Lane Fox p.198"/> | ||

*'''Artaxerxes II of Persia and Tiridates''' | *'''Artaxerxes II of Persia and Tiridates''' | ||

The Persian king, distraught at the death of his beloved eunuch, found consolation in placing the dead youth's cloak over the shoulders of Aspasia, his Greek hetaira.<ref>Aelian, Var. Hist. 12.1</ref> | ::The Persian king, distraught at the death of his beloved eunuch, found consolation in placing the dead youth's cloak over the shoulders of Aspasia, his Greek hetaira.<ref>Aelian, Var. Hist. 12.1</ref> | ||

*'''Archelaus I of Macedon and Craterus (or Crateuas)''' | *'''Archelaus I of Macedon and Craterus (or Crateuas)''' | ||

The king of Macedon was assassinated in 399 BCE by this eromenos, upon reneging on a promise to give the boy his daughter in marriage.<ref>Aelian, ''Varia Historia, 8.9</ref> | ::The king of Macedon was assassinated in 399 BCE by this eromenos, upon reneging on a promise to give the boy his daughter in marriage.<ref>Aelian, ''Varia Historia, 8.9</ref> | ||

*'''Amyntas the Little and Derdas''' | *'''Amyntas the Little and Derdas''' | ||

The couple is cited by Aristotle as another exampled of an eromenos killing his erastes (in 393/4), in this case for a boast by the latter that he had "possessed" the youth.<ref>Aristotle, ''The Politics" V.xM. B. Hatzopoulos''Cultes et rites de passage en Macedoine''</ref> | ::The couple is cited by Aristotle as another exampled of an eromenos killing his erastes (in 393/4), in this case for a boast by the latter that he had "possessed" the youth.<ref>Aristotle, ''The Politics" V.xM. B. Hatzopoulos''Cultes et rites de passage en Macedoine''</ref> | ||

*'''Lysias and Theodotus''' | *'''Lysias and Theodotus''' | ||

Though already in his early fifties, Lysias took on an eromenos from Platea around 394. The youth, however, had already signed a companionship contract in the amount of 300 drachmae with a certain Simon, who, claiming prior rights to the boy, proceeded to stalk him, resorting to several kidnapping attempts. As a result of that, and the street brawls which ensued, the case was heard before the Areopagus.<ref>Lysias, ''Against Simon,'' 1-26,44, 47-48John Addington Symonds, ''A problem in Greek Ethics,'' XII, p.64</ref> | ::Though already in his early fifties, Lysias took on an eromenos from Platea around 394. The youth, however, had already signed a companionship contract in the amount of 300 drachmae with a certain Simon, who, claiming prior rights to the boy, proceeded to stalk him, resorting to several kidnapping attempts. As a result of that, and the street brawls which ensued, the case was heard before the Areopagus.<ref>Lysias, ''Against Simon,'' 1-26,44, 47-48John Addington Symonds, ''A problem in Greek Ethics,'' XII, p.64</ref> | ||

*'''Alexander of Pherae and Pitholaus''' | *'''Alexander of Pherae and Pitholaus''' | ||

The tyrant took the youngest brother of his wife, Thebes, as eromenos, against the boy's will and tied him up. His wife pleaded with him incessantly for the boy's release. Exasperated with her demand, Alexander killed the boy. In revenge, Thebes and her remaining brothers assassinated the tyrant in 357.<ref>Plutarch, ''Amores;'' XXIIIXenophon, ''Hellenics'' VI.4Diodorus Siculus XVI.14</ref> | ::The tyrant took the youngest brother of his wife, Thebes, as eromenos, against the boy's will and tied him up. His wife pleaded with him incessantly for the boy's release. Exasperated with her demand, Alexander killed the boy. In revenge, Thebes and her remaining brothers assassinated the tyrant in 357.<ref>Plutarch, ''Amores;'' XXIIIXenophon, ''Hellenics'' VI.4Diodorus Siculus XVI.14</ref> | ||

*'''Theomedon and Eudoxus of Cnidus''' | *'''Theomedon and Eudoxus of Cnidus''' | ||

The astronomer had been the eromenos of the doctor Theomedon, with whom he later traveled to Athens in order to study with Plato.<ref>Diogenes Laertius; VIII.87</ref> | ::The astronomer had been the eromenos of the doctor Theomedon, with whom he later traveled to Athens in order to study with Plato.<ref>Diogenes Laertius; VIII.87</ref> | ||

*'''Aristippus of Cyrene and Euthychides''' | *'''Aristippus of Cyrene and Euthychides''' | ||

The youth was a slave of the philosopher, compared by him with the students of Socrates.<ref>Diogenes Laërtius, ii.74</ref> | ::The youth was a slave of the philosopher, compared by him with the students of Socrates.<ref>Diogenes Laërtius, ii.74</ref> | ||

*'''Agesilaus II and Megabates''' | *'''Agesilaus II and Megabates''' | ||

During his campaign in Asia in 396, the king fell in love with the very handsome son of a Persian officer, Spithridates, who had joined the Spartan forces. Agesialus struggled to master his excessive fondness for the boy, going as far as rejecting Megabates' greeting kiss. When the father changed sides again and took his son with him, the king was greatly distressed.<ref>Plutarch, ''Lives'' "Agesilaus"</ref> | ::During his campaign in Asia in 396, the king fell in love with the very handsome son of a Persian officer, Spithridates, who had joined the Spartan forces. Agesialus struggled to master his excessive fondness for the boy, going as far as rejecting Megabates' greeting kiss. When the father changed sides again and took his son with him, the king was greatly distressed.<ref>Plutarch, ''Lives'' "Agesilaus"</ref> | ||

| Line 312: | Line 307: | ||

*'''Diopeithes of Sounion, and Hegesandros of Sounion''' | *'''Diopeithes of Sounion, and Hegesandros of Sounion''' | ||