Hadrian: Difference between revisions

Dandelion moved page Hadrian to Hadrian (Roman emperor) Tag: New redirect |

Replaced the redirect link with the new content of the page Tag: Removed redirect |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Marble Busts of Hadrian & Antinous, from Rome, Roman Empire, British Museum (16497688477).jpg|264px|right|thumb|Left foreground: Marble bust of the Emperor Hadrian shown naked. Roman, circa 117–138 AD. London, British Museum, 1805,0703.94. Right background: Marble portrait head from a statue of Antinous (as Dionysus?) wearing a wreath of ivy. Roman, circa 130–140 AD. Found on the Janiculine Hill at Lazio in Rome, Italy. London, British Museum, 1805,0703.97.]] | |||

{{History}} | |||

'''Caesar Traianus Hadrianus''' (24 January 76 AD – 10 July 138 AD), known as '''Hadrian''', was [[Roman emperor]] from 117 to 138 AD. He was born into a Roman Italo-Hispanic family that settled in [[Spain]] from the Italian city of Atri in Picenum. His father was of senatorial rank and was a first cousin of Emperor [[Trajan]]. He married Trajan's grand-niece Vibia Sabina early in his career, before Trajan became emperor and possibly at the behest of Trajan's wife Pompeia Plotina. Plotina and Trajan's close friend and adviser Lucius Licinius Sura were well disposed towards Hadrian. When Trajan died, his widow claimed that he had nominated Hadrian as emperor immediately before his death. | |||

Rome's military and Senate approved Hadrian's succession, but four leading senators were unlawfully put to death soon after. They had opposed Hadrian or seemed to threaten his succession, and the Senate held him responsible for it and never forgave him. He earned further disapproval among the elite by abandoning Trajan's expansionist policies and territorial gains in Mesopotamia, Assyria, Armenia, and parts of Dacia. Hadrian preferred to invest in the development of stable, defensible borders and the unification of the empire's disparate peoples. He is known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Britannia. | |||

Hadrian energetically pursued his own Imperial ideals and personal interests. He visited almost every province of the Empire, accompanied by an Imperial retinue of specialists and administrators. He encouraged military preparedness and discipline, and he fostered, designed, or personally subsidised various civil and religious institutions and building projects. In Rome itself, he rebuilt the Pantheon and constructed the vast Temple of Venus and Roma. In Egypt, he may have rebuilt the Serapeum of Alexandria. He was an ardent admirer of [[Ancient Greece|Greece]] and sought to make Athens the cultural capital of the Empire, so he ordered the construction of many opulent temples there. His intense relationship with the Bithynian Greek youth [[Antinous]] and the latter's untimely death led Hadrian to establish a widespread cult late in his reign. He suppressed the Bar Kokhba revolt in Judaea, but his reign was otherwise peaceful. | |||

Hadrian's last years were marred by chronic illness. He saw the Bar Kokhba revolt as the failure of his panhellenic ideal. He executed two more senators for their alleged plots against him, and this provoked further resentment. His marriage to Vibia Sabina had been unhappy and childless; he adopted Antoninus Pius in 138 AD and nominated him as a successor, on the condition that Antoninus adopt Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus as his own heirs. Hadrian died the same year at Baiae, and Antoninus had him deified, despite opposition from the Senate. Edward Gibbon includes him among the Empire's "Five Good Emperors", a "benevolent dictator"; Hadrian's own Senate found him remote and authoritarian. He has been described as enigmatic and contradictory, with a capacity for both great personal generosity and extreme cruelty and driven by insatiable curiosity, self-conceit, and ambition.<ref>Ando, Clifford "Phoenix", ''Phoenix'', 52 (1998), pp. 183–185. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/1088268 JSTOR 1088268]</ref> | |||

==Relationship with Antinous== | |||

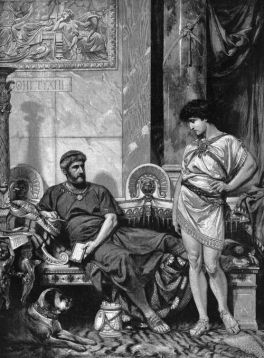

[[File:After Otto Knille - Hadrian and Antinous in the Palace at Lochias in Alexandria.jpg|264px|left|thumb|''Hadrian and Antinous in the Palace at Lochias in Alexandria''. Engraving after a painting by Otto Knille (1832–1898).]] | |||

The Emperor Hadrian spent much time during his reign touring his Empire, and arrived in Claudiopolis (present day Bolu, Turkey), in the Roman province of Bithynia et Pontus, in June 123 AD, which was probably when he first encountered Antinous, then aged around 12. Given Hadrian's personality, Royston Lambert, biographer of Antinous, thought it unlikely that they had become lovers at this point, instead suggesting it probable that Antinous had been selected to be sent to Italy, where he was probably schooled at the imperial paedagogium at the Caelian Hill. Hadrian meanwhile had continued to tour the Empire, only returning to Italy in September 125 AD (Antinous being around 14 years old at the time), when he settled into his villa at Tibur. It was at some point over the following three years that Antinous became his personal favourite, for by the time he left for Greece three years later, he brought Antinous with him in his personal retinue, the youth being aged around 17. | |||

Lambert described Antinous as "the one person who seems to have connected most profoundly with Hadrian" throughout the latter's life. Hadrian's marriage to Sabina was unhappy, and there is no reliable evidence that he ever expressed a sexual attraction for women, in contrast to much reliable early evidence that he was sexually attracted to boys and young men. | |||

It is known that Hadrian believed Antinous to be intelligent and wise, and that they had a shared love of hunting, which was seen as a particularly manly pursuit in Roman culture. Although none survive, it is known that Hadrian wrote both an autobiography and erotic poetry about his boy favourites; it is therefore likely that he wrote about Antinous. Early sources are explicit that the relationship between Hadrian and Antinous was sexual. During their relationship, there is no evidence that Antinous ever used his influence over Hadrian for personal or political gain. | |||

Hadrian arrived in Egypt before the Egyptian New Year on 29 August 130 AD (when Antinous was aged around 19). Hadrian and Antinous held a lion hunt in the Libyan desert; a poem on the subject by the Greek Pankrates is the earliest evidence that they travelled together.<ref>Opper, ''Hadrian: Empire and Conflict'', p. 173</ref> | |||

While Hadrian and his entourage were sailing on the Nile, Antinous drowned. The exact circumstances surrounding his death are unknown, and accident, suicide, murder and religious sacrifice have all been postulated. ''Historia Augusta'' offers the following account: | |||

{{quote|text=During a journey on the Nile he lost Antinous, his favourite, and for this youth he wept like a woman. Concerning this incident there are varying rumours; for some claim that he had devoted himself to death for Hadrian, and others – what both his beauty and Hadrian's sensuality suggest. But however this may be, the Greeks deified him at Hadrian's request, and declared that oracles were given through his agency, but these, it is commonly asserted, were composed by Hadrian himself.<ref>''Historia Augusta'' (c. 395) Hadr. 14.5–7</ref>}} | |||

Hadrian founded the city of Antinoöpolis in Antinous' honour on 30 October 130 AD. | |||

==References== | |||

{{reflist}} | |||

==See also== | |||

*[[Catamite]] | |||

*[[Historical boylove relationships in ancient Rome]] | |||

*[[Historical boylove relationships in ancient Greece]] | |||

*[[Pederasty in ancient Greece]] | |||

==External links== | |||

*[http://www.thefullwiki.org/Hadrian Hadrian (The Full Wiki)] | |||

{{Navbox Ancient Rome|collapsed}} | |||

[[Category:Ancient Rome]] | |||

Latest revision as of 09:57, 16 August 2021

| Part of the boylove history series |

|

| Portal:History |

Caesar Traianus Hadrianus (24 January 76 AD – 10 July 138 AD), known as Hadrian, was Roman emperor from 117 to 138 AD. He was born into a Roman Italo-Hispanic family that settled in Spain from the Italian city of Atri in Picenum. His father was of senatorial rank and was a first cousin of Emperor Trajan. He married Trajan's grand-niece Vibia Sabina early in his career, before Trajan became emperor and possibly at the behest of Trajan's wife Pompeia Plotina. Plotina and Trajan's close friend and adviser Lucius Licinius Sura were well disposed towards Hadrian. When Trajan died, his widow claimed that he had nominated Hadrian as emperor immediately before his death.

Rome's military and Senate approved Hadrian's succession, but four leading senators were unlawfully put to death soon after. They had opposed Hadrian or seemed to threaten his succession, and the Senate held him responsible for it and never forgave him. He earned further disapproval among the elite by abandoning Trajan's expansionist policies and territorial gains in Mesopotamia, Assyria, Armenia, and parts of Dacia. Hadrian preferred to invest in the development of stable, defensible borders and the unification of the empire's disparate peoples. He is known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Britannia.

Hadrian energetically pursued his own Imperial ideals and personal interests. He visited almost every province of the Empire, accompanied by an Imperial retinue of specialists and administrators. He encouraged military preparedness and discipline, and he fostered, designed, or personally subsidised various civil and religious institutions and building projects. In Rome itself, he rebuilt the Pantheon and constructed the vast Temple of Venus and Roma. In Egypt, he may have rebuilt the Serapeum of Alexandria. He was an ardent admirer of Greece and sought to make Athens the cultural capital of the Empire, so he ordered the construction of many opulent temples there. His intense relationship with the Bithynian Greek youth Antinous and the latter's untimely death led Hadrian to establish a widespread cult late in his reign. He suppressed the Bar Kokhba revolt in Judaea, but his reign was otherwise peaceful.

Hadrian's last years were marred by chronic illness. He saw the Bar Kokhba revolt as the failure of his panhellenic ideal. He executed two more senators for their alleged plots against him, and this provoked further resentment. His marriage to Vibia Sabina had been unhappy and childless; he adopted Antoninus Pius in 138 AD and nominated him as a successor, on the condition that Antoninus adopt Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus as his own heirs. Hadrian died the same year at Baiae, and Antoninus had him deified, despite opposition from the Senate. Edward Gibbon includes him among the Empire's "Five Good Emperors", a "benevolent dictator"; Hadrian's own Senate found him remote and authoritarian. He has been described as enigmatic and contradictory, with a capacity for both great personal generosity and extreme cruelty and driven by insatiable curiosity, self-conceit, and ambition.[1]

Relationship with Antinous

The Emperor Hadrian spent much time during his reign touring his Empire, and arrived in Claudiopolis (present day Bolu, Turkey), in the Roman province of Bithynia et Pontus, in June 123 AD, which was probably when he first encountered Antinous, then aged around 12. Given Hadrian's personality, Royston Lambert, biographer of Antinous, thought it unlikely that they had become lovers at this point, instead suggesting it probable that Antinous had been selected to be sent to Italy, where he was probably schooled at the imperial paedagogium at the Caelian Hill. Hadrian meanwhile had continued to tour the Empire, only returning to Italy in September 125 AD (Antinous being around 14 years old at the time), when he settled into his villa at Tibur. It was at some point over the following three years that Antinous became his personal favourite, for by the time he left for Greece three years later, he brought Antinous with him in his personal retinue, the youth being aged around 17.

Lambert described Antinous as "the one person who seems to have connected most profoundly with Hadrian" throughout the latter's life. Hadrian's marriage to Sabina was unhappy, and there is no reliable evidence that he ever expressed a sexual attraction for women, in contrast to much reliable early evidence that he was sexually attracted to boys and young men.

It is known that Hadrian believed Antinous to be intelligent and wise, and that they had a shared love of hunting, which was seen as a particularly manly pursuit in Roman culture. Although none survive, it is known that Hadrian wrote both an autobiography and erotic poetry about his boy favourites; it is therefore likely that he wrote about Antinous. Early sources are explicit that the relationship between Hadrian and Antinous was sexual. During their relationship, there is no evidence that Antinous ever used his influence over Hadrian for personal or political gain.

Hadrian arrived in Egypt before the Egyptian New Year on 29 August 130 AD (when Antinous was aged around 19). Hadrian and Antinous held a lion hunt in the Libyan desert; a poem on the subject by the Greek Pankrates is the earliest evidence that they travelled together.[2]

While Hadrian and his entourage were sailing on the Nile, Antinous drowned. The exact circumstances surrounding his death are unknown, and accident, suicide, murder and religious sacrifice have all been postulated. Historia Augusta offers the following account:

During a journey on the Nile he lost Antinous, his favourite, and for this youth he wept like a woman. Concerning this incident there are varying rumours; for some claim that he had devoted himself to death for Hadrian, and others – what both his beauty and Hadrian's sensuality suggest. But however this may be, the Greeks deified him at Hadrian's request, and declared that oracles were given through his agency, but these, it is commonly asserted, were composed by Hadrian himself.[3]

Hadrian founded the city of Antinoöpolis in Antinous' honour on 30 October 130 AD.

References

- ↑ Ando, Clifford "Phoenix", Phoenix, 52 (1998), pp. 183–185. JSTOR 1088268

- ↑ Opper, Hadrian: Empire and Conflict, p. 173

- ↑ Historia Augusta (c. 395) Hadr. 14.5–7

See also

- Catamite

- Historical boylove relationships in ancient Rome

- Historical boylove relationships in ancient Greece

- Pederasty in ancient Greece