Japan: Difference between revisions

| (123 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{History}} | |||

'''Japan''' | '''Japan''' (in Japanese, Nippon or Nihon -- '''日本''') is an island nation located east of China, Korea and Russia, which was originally inhabited by fishermen belonging to the Ainu (アイヌ) peoples (who today represent no more than about 1 percent of the total population) but now populated almost entirely by Mongoloid immigrants from the mainland Asian land mass, immigration which occurred in two distinct waves during the Japanese prehistoric period. About 0.5% of the residents of Japan are of Korean descent -- often the children of workers from the time Japan forcefully annexed Korea (1910-1945), who, while born in Japan, have had their nationality hotly contested by other native-born Japanese nationals. About 0.4% of the population are Chinese, and 0.6% "other". | ||

[[Image:120px-Yoshitoshi Ariwara Narihira.jpg|thumb|Ariwara no Narihira|left]] | |||

In terms of language and customs, Japanese civilization has been very strongly influenced by neighboring countries (China, Korea, and India) as well as by the distant cultures (beginning in the Meiji restoration [1868]) of Europe and the USA, while trying at the same time to preserve its unique characteristics. For example, Japanese cuisine is largely of native origin, though Chinese-style dishes are quite popular as well. | |||

Japan remained closed to Western influence for over two centuries, from 1641 to 1853, after having expelled the Christian missionaries, as well as most other foreigners, and severely limiting external trade. However, in 1853 it was forced to open up its borders by threats of military attack made by the US war fleet commanded by Commodore Matthew Perry which was sent by President Millard Fillmore to open Japan to trade, by whatever means possible, including acts of war.<ref>Commodore Perry's expedition to force an "opening up" of Japan to trade with Western countries: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perry_Expedition</ref> This was the beginning of the end of normal and healthy BoyLove in Japan. | |||

The [[wakashudō]], , also called ''nanshoku,'' describes a social, emotional and sexual relationship formed between an adult male and a young [[boy]]. Existing since at least the eighth century and popular until the nineteenth, it is the most durable [[pederastic]] institution attested to in the history of mankind. | |||

== Notes on Japanese social patterns == | |||

[[Confucianism]] is almost universally practiced, along with Buddhism. The Confucian social order in Japan, from highest to lowest class, is the [[samurai]] (warriors), the farmers and artisans, the traders and businessmen, and, finally, the Burakumin (the outcasts, very similar to the "untouchable" class in the Indian Hindu system of social stratification). | |||

However, aside from the treatment of those descendants of the Burakumin class, the social structure usually gives greater weight to differences in age rather than to social status. | |||

Japanese culture places a lot of emphasis on respecting those who are older than ones self. Elderly persons are treated with the utmost respect, even to the point of having their own holiday, <i>Keiro no Hi</i>, or "Respect for the Aged Day". [http://www.officeholidays.com/countries/japan/respect_the_aged.php] This may be because of the [[Shinto]] belief that things accrue power as they become older. | |||

At the same time, children in Japan also have their own days: <i>Kodomo no Hi</i>, also called "Boy's Day" or "Children's day", <i>Hinamatsuri</i>, also called "Girl's Day" or "Doll's Day", and "7-5-3 Day", a day to celebrate children aged 7, 5, and 3. [http://aboutjapan.japansociety.org/content.cfm/kodomo_no_hi_childrens_day_celebration] [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hinamatsuri][http://iroha-japan.net/iroha/B05_initiation/07_753.html] | |||

[[Image:Japanese imperial seal 1000x1000.gif|150px|left]] | [[Image:Japanese imperial seal 1000x1000.gif|150px|left]] | ||

There are no Japanese [[taboo]] regarding anal sex (excrement | There are no Japanese [[taboo|taboos]] regarding anal sex (human excrement has not, at least, traditionally, been seen as some kind of "dirty" waste, but rather as a natural fertilizer recycled for use in fertilizing crops growing in the fields). Anal intercourse, not being seen as "disgusting" or "dirty" as in the West, was therefore not stigmatized except for any possible pain it might cause the passive partner. Also, the the passive role in anal intercourse was not seen as being something demeaning nor feminizing, as it tended to be in Western Greek homosexuality. | ||

It should be noted in this regard that the chrysanthemum flower is both the symbol of the Emperor, and of the anus in ''nanshoku.'' | |||

{{Clr}} | {{Clr}} | ||

== Nanshoku and | ==Nanshoku and wakashudō== | ||

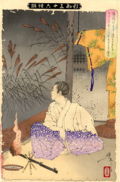

[[Image:1661 A Shudo relationship (Tale of Shudo) 513x628.jpg|right|thumb|280px| | [[Image:1661 A Shudo relationship (Tale of Shudo) 513x628.jpg|right|thumb|280px| Depiction of a [[Shudo]] relationship, from 衆道物語 (Tale of Shudo), 1661 (Japan) -- A samurai and his young disciple ]] | ||

A samurai and his young disciple | |||

In the pre-modern period, Japanese [[pederasty]] | In the pre-modern period, there were two distinct terms used to describe the Japanese form of [[pederasty]]: | ||

* ''nanshoku''男色( | * ''[[nanshoku]]'' (男色) (alternate reading, ''danshoku'') signifies "manly lust" or "lust between males". It refers to [[pederastic]] or [[homosexual]] sexual practices. See [https://www.ipce.info/library_3/files/nanshoku_en.htm] | ||

* '' | * ''[[wakashudō]]'' (若衆道) consists of the character ''dō'' (道), adapted from the Chinese character "tao" meaning "the path" (along which we progress); and the term ''wakashū'' (若衆), "young person" or more specifically, "boy": the term ''wakashudō'' literally means "the way of the boys." <br>It may also take the abbreviated forms ''shudō'' (衆道) and ''nyakudō'' (若道). | ||

It also | |||

* | * Similarly, we find the term ''bidō'' (美道); the "beautiful way". | ||

In brief, ''nanshoku'' evokes the concepts of pleasure, passion, and virility; while ''wakashudō'' focuses more on the young boy's guided pursuit of knowledge and wisdom. | |||

The '' | The ''wakashū'' (young boys) involved in ''wakashudō'' relationships belonged to a well-defined age group, whose boundaries could vary from five to twenty-five years of age, though the most appropriate ages were often considered to be from fourteen to eighteen. Note, however, that puberty probably occurred later than it does today in Japan, and, furthermore, the relative lack of body hair of the Japanese may give them a longer-lasting youthful appearance than their European counterparts. | ||

== Religions == | == Religions == | ||

There | Religion in Japan consists mainly of the animistic [[Shinto]] belief system and [[Buddhist|Buddhism]]. These beliefs are tempered with Chinese [[Confucianism]]. Christians now account for about 2% of the population, while [[Islam]] is virtually nonexistent. | ||

There are no sexual taboos in Shintoism, which considers sexual activity to be an absolute pleasure, as does Confucianism as well. | |||

In Buddhism, each | In Buddhism, each monk takes vows to forsake all sexual thoughts involving women. While total sexual abstinence is seen as preferable, [[sexuality|sexual activity]] with males is seen as a last resort to satiate the inevitable desire for sexual activity. | ||

[[Taoism]], which strongly influences Japanese Zen Buddhism, emphasizes balance. Taoism holds that [[heterosexual]] activity in humans involves a catastrophic loss of energy, and therefore should be moderated. This risk does not exist in the case of homosexual sex. | |||

None of these | None of these religious or philosophical practices considers pederasty or homosexuality as being unnatural. | ||

=== Shinto deities === | === Shinto deities === | ||

During Tokugawa shogunate (from the | During the Tokugawa shogunate (from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries), many Shinto gods were considered to be the guardian deities of [[nanshoku]], in particular, Hachiman (八幡神), Myoshin, Shinmei and Tenjin (天神). Also evoked was [[Hotei]] (布袋) ("Budai" in China), the "laughing Buddha," often surrounded by beautiful and reverent boys. | ||

The writer [[Ihara Saikaku]] says | The writer [[Ihara Saikaku]] jokingly says that, because there are no women in the first three generations of the divine genealogy described in ''Nihon shoki'' (日本書紀) ("The Chronicles of Japan"), the gods have always engaged in sexual activity - and he considers this as the true origin of ''nanshoku.'' <ref>Gary P. Leupp, ''Male colors : the construction of homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan'', University of California Press, 1999, ISBN 0-520-20909-5, p. 32-34.</ref> | ||

=== Buddhist deities === | === Buddhist deities === | ||

Buddhism | Buddhism was imported from China beginning in the fifth century, eventually evolving in Japan into thirteen major schools. It gained particular importance during the Nara period (8th century AD). | ||

Monju | Monju (文殊) or Monjushiri (文殊師利) is the Japanese name for [[Mañjuśrī]], the great bodhisattva <ref>A bodhisattva can be defined as an "active saint" after reaching perfection, he deferred his entry into nirvana to help all beings find their deliverance.</ref> of wisdom. However, according to later traditions, this deity would be the originator of ''nanshoku.'' <ref>Louis Crompton, Homosexuality and civilization, Cambridge (Massachusetts), Harvard University Press, 2003, p. 413f.</ref> It should be noted that one of the deities names in Sanskrit is Mañjuśrī Kumārabhūta ("The Youth"), which, in Chinese, may also be called ''Rǔtóng wénshū'' (孺童文殊) "the young child Wenshu," or Fǎwángzǐ (法王子) "the Son of the Buddha." | ||

=== Spiritual Masters === | === Spiritual Masters === | ||

The | Despite the fact that in some cultures the local form of Buddhism adhered to may object to some extent to homosexual practices, male homosexuality in Japan is closely associated with Japanese Buddhist institutions. | ||

The Buddhist monk ''Kūkai'' (空海), also known as Kōbō-Daishi (弘法大師) (774-835), was the founder of the [[tantric]] branch of Shingon Buddhism (真言), as well as an important monastic community. He is said to have introduced pederasty to Japan on his return from China in 806; but some consider that his reputation for having done so was either initially created, or later exaggerated, by the Christian missionary Francis Xavier. Mount ''Kōya'' (高野山), the name which also refers to the monastery founded there by Kūkai, was commonly used until the end of the pre-modern era in Japan to refer to pederastic relationships. | |||

== History == | == History == | ||

| Line 71: | Line 73: | ||

=== The beginnings of nanshoku === | === The beginnings of nanshoku === | ||

No | No sources mention the possible existence in ancient times of pederastic practices in Japan. | ||

Several descriptions of homosexual acts exist in ancient literary works, but most are too subtle to be | Several descriptions of homosexual acts exist in ancient literary works, but most are too subtle to be established unambiguously; displays of physical affection between same sex couples were common and accepted at that time. The first sources citing pederastic relationships date back to the Heian period, around the eleventh century. | ||

In [[The Tale of Genji]] 源氏物語 | In [[The Tale of Genji]] (源氏物語) written around that time, men are often shown to be attracted to the beauty of young boys. One scene shows, for example, the hero being rejected by a woman, and then later sleeping with the little brother of the woman instead: | ||

{{cquote|Well, at least you will | {{cquote|Well, at least you will never abandon me." Genji pulled the boy next to him so they would sleep together. <br>The boy was delighted, as was Genji with the boy's juvenile charms. Genji said, for his part, that he found the boy more attractive than his frigid sister.}} | ||

''The Tale of Genji'' is | ''The Tale of Genji'' is, of course, only a novel, but some other accounts from the same era and until the first half of the fourteenth century, also contain descriptions of pederasty activities. Some of them even implicate emperors as having been involved in relationships with "beautiful boys for sexual purposes". <ref>Gary P. Leupp, ''Male colors : the construction of homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan'', University of California Press, 1999, ISBN 0-520-20909-5, p. 26.</ref> But they did not give rise to any pederastic tradition, unlike what occurred in China in antiquity. | ||

=== | ===The era of the founding of monasteries=== | ||

Monastic communities | Monastic communities began to be founded beginning in the ninth century. By the end of the sixteenth century, the number amounted to about ninety thousand. Some were home to a thousand men and boys, and the largest up to three thousand. Monks would keep as novices children or teenagers called [[chigo]] (稚児). These young people, often from large families, came to learn the Buddhist liturgy, or to prepare themselves for a monastic career. | ||

Sexual relationships between a monk and a ''chigo'' were common. They included anal sex. Each partner was given a name and took a specific role: the elder (''[[nenja]]'' (念者) -- the lover, admirer -- ''nenyū, anibun, anikibun, kyūkyū'') and the youth (''[[wakashū]]'' [若衆] - young person -- ''nyake, otōtobun'') contracted a fraternal liaison (''kyōdai keiyaku'' or ''kyōdai chigiri'') and swore loyalty to each other. | |||

In | In 1419 and 1436, a ban was placed on the monks: Not a ban on having sexual relations with their novices, but a ban on dressing them as girls. However, it was expected that these boys would one day became men, and that their female costumes were meant to be purely aesthetic and [[erotic]], and not meant to feminize their behavior. | ||

===== European observations ===== | ===== European observations ===== | ||

The first Europeans to | The first Europeans visitors to Japan were shocked by the frequency and openness of pederastic relationships. The Portuguese Jesuit Alessandro Valignani, observed in 1591: | ||

{| | {{cquote|Young boys and their partners do not consider the matter as something serious, neither do they hide what they do. In fact, they see what they do as being honorable, and speak openly about it. Not only do they ''not'' take the doctrine of the monks as being something wrong, they themselves practice this custom, holding it to be absolutely natural and, at the same time, something virtuous.}} | ||

=== The age of the samurai === | |||

=== The | |||

The age of the samurai began in the eighth century, at the end of the Nara period, <ref> At that time it was also decided that no woman would be allowed to ascend to the throne, because of their excessive tendency to "devotion"???MUST CHECK???. The ban would remain in effect for nearly a thousand years.</ref> when the first professional warriors appeared; young cavalry archers from affluent backgrounds. They formed a militia of 3964 men, who later led to the formation of the samurai caste in the tenth century. | |||

Numerous samurai first became novices in a monastery. Monastic morals therefore came to be used as models for male [[love]], the model for those males who lived with warriors. The feudal structure of society contributed in the same way in structuring these relationships. | |||

As between a monk and a novice, the relationship between two samurai begins with [[oaths]] | As between a monk and a novice, the relationship between two samurai begins with fraternal [[oaths]], possibly in writing, which then constituted a genuine contract (in these cases, the relationship would be monogamous). Many of these contractual oaths have been preserved, including that between [[Takeda Shingen]] (best known in the West as the central protagonist of ''Kagemusha'' in the Kurosawa film of the same name) and his lover, Dansuke Kasuga, then aged twenty-two and sixteen years, respectively. | ||

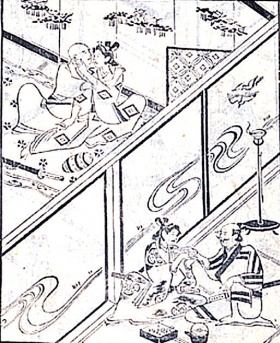

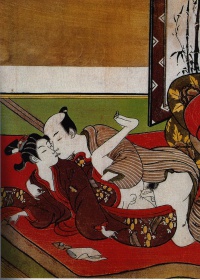

[[Image:SUZUKI Harunobu 1750c Shunga (detail) 1386x1941.jpg|right|thumb|200px| | [[Image:SUZUKI Harunobu 1750c Shunga (detail) 1386x1941.jpg|right|thumb|200px|Suzuki Harunobu, "Shunga", series of 24 erotic prints Mid- eighteenth century c. 1750 Victoria and Albert Museum, London]] | ||

Unlike | Unlike ancient [[:Category:Ancient Greece|Greek pederasty]], the initiative to start such a relationship fell on the boy. But as the samurai apprentice was often very young, between ten and thirteen years of age when initiated in ''wakashudō'' -- it may have been the parent who usually sought out a master for the boy. | ||

The young samurai | The young samurai served his elder during military campaigns. In peacetime, he often would act the part of a [[page]] to the older partner, and be considered to possess feminine allures. | ||

'' | ''Wakashudō'' principles are part of a rich literary tradition; we find mentions in works such as [[Hagakure]] or in various manuals written for the samurai. In its educational, military and aristocratic aspects, the ''wakashudō'' tradition strongly resembled the ancient Greek pederastic tradition. | ||

This practice was held in high regard and saw | This practice was held in very high regard and saw encouragement among the samurai . It was considered beneficial for the boy in that it taught the boy virtue, honesty and a sense of beauty. The love of women, in contrast, was thought to feminize men. | ||

{| | {{cquote|The nanshoku is the leisure of the Samurai: how could it be detrimental to good government? <ref>Eijima Kiseiki, Huhwan meishu kenshō, XVIIe siècle. [The orthography and title of this still requires verification]</ref>}} | ||

=== Traditions artificially corrupted === | |||

=== | |||

From the seventeenth century, as the samurai were inspired | From the seventeenth century, as the samurai were being inspired by the ''nanshoku'' practiced by monks, the bourgeois merchant class began to imitate the man-boy loves of the samurai, but adapting them according to their own principles. | ||

The values | The values of love and honor that previously prevailed were then gradually replaced by those of simple pleasure and money. The educational aspects gave way to [[prostitution]] , the manhood to effeminacy. In return, the moral degradation eventually came to contaminate the Samurai monastic classes. | ||

==== Prostitution ==== | ==== Prostitution ==== | ||

During the Edo period ( | During the Edo period (1600-1868) the ''onnagata'', as were called the boy or young male actors who interpreted adult female roles on stage in ''kabuki'' theatre, also often worked on the side as prostitutes. | ||

The [[KAGEMA]] were male prostitutes working in [[brothels]] | The [[KAGEMA]] were male prostitutes working in specialized [[brothels]], the ''kagemajaya'' (陰間茶屋) called "''KAGEMA"''tea houses. In the nineteenth century there existed twenty-four red light districts for boy prostitution in Tokyo. | ||

Both ''KAGEMA onnagata'' | Both the ''KAGEMA'' and the ''onnagata'' were prized by refined followers of ''nanshoku.'' A male prostitute | ||

could be paid much more than an expensive female prostitute: An expensive female prostitute could receive 5 ''monme'' for one tryst, while a boy could be valued at between 43 and 129 ''monme'' for the same.<ref> | |||

The ''monme'' is an ancient Japanese unit of weight and measure equivalent to 3.75 grams of silver. For comparison, the annual salary of a servant to a wealthy family was about 240 ''monme''.</ref> | |||

== Modern Japan == | == Modern Japan == | ||

With the | With the beginnings of the Meiji Restoration and the growing influence -- and the wholesale importation -- of facets of Western cultures (and the founding of a legal system based on the German model), all [[homoerotic]] practices, including ''wakashudō'', began to be subject to criminal sanctions and to rapid decline in the late nineteenth century. | ||

=== Man-boy sex === | === Man-boy sex === | ||

***IMPORTANT NOTE: Laws regarding intergenerational sexual relationships can change quickly, and new penalties may be draconian. The following ''should not'' be taken as legal advice!*** | |||

The [[age of consent|minimum legal age]] for sexual relations between men and boys is set differently in the forty seven different prefectures (or departments) in Japan. However, the "centralized" legislation passed by the Japanese Diet takes primacy over local laws. But if the trial courts apply the local laws, the appellate courts must follow the centralized law. | |||

This system | This somewhat complex system, which is partly dependent on local features, could result in a man being condemned in some prefectures for having sex with a boy of fourteen. But if he appeals his case - which is in his best interest - it will be decided according to the centralized law, which permits adult-minor relationships from thirteen years of age: He will then eventually be acquitted. | ||

=== Erotic materials === | === Erotic materials === | ||

====== Real and virtual pornography ====== | ====== Real and virtual pornography ====== | ||

The production, distribution and possession of [[child pornography]] is prohibited in Japan if it involves actual minors. | |||

In June 2014, the simple possession of such images became a crime punishable with imprisonment of up to a year, and a fine of up to one million yen. However, a one-year period to come into compliance with the new law was provided for. | |||

Imaginary representations (drawings, etc.) which do not involve images of real children are still legal. | |||

== Literature == | |||

The | * Several anonymous [[chigo monogatari]] tell of the love of monks for their young novices. | ||

* [[Ihara Saikaku]] <ref>Parfois transcrit Saïkakou Ebara.</ref> (井原 西鶴) or Saikaku (1642-1693): [[nanshoku Okagami]] (男色大鏡) ''(The Great Mirror of Male Love),'' 1689. | |||

== Fine Arts == | |||

==== | |||

=== Shunga === | |||

'''Shunga''' (春画) is a Japanese term for [[erotic art]]. Most shunga are a type of [[ukiyo-e]], usually executed in woodblock print format. While rare, there still exist erotic painted handscrolls which predate the Ukiyo-e movement.<ref name=Helsinki>{{cite book | title=Forbidden Images – Erotic art from Japan's Edo Period |publisher=Helsinki City Art Museum |location=Helsinki, Finland |language=Finnish | year=2002 | pages=23–28|isbn=951-8965-53-6}}</ref> Translated literally, the Japanese word ''shunga'' means ''picture of spring''; "spring" being a common euphemism for sex. | |||

=== Manga === | |||

'''[[Manga and anime|Manga]]''' (漫画) are comics created in Japan, or by those creating comics in the Japanese language, conforming to a style developed in Japan in the late 19th century.<ref>Lent 2001, pp. 3–4, Gravett 2004, p. 8</ref> They have a long and complex pre-history in earlier Japanese art. <ref>Kern 2006, Ito 2005, Schodt 1986</ref> | |||

'''[[Manga and anime|Manga]]''' 漫画 are | |||

=== Shotacon === | |||

'''[[Manga_and_anime#Shotacon|Shotacon]]''' (ショタコン) is Japanese slang. It is a portmanteau of the phrase, "Shōtarō complex" (正太郎コンプレックス = shōtarō konpurekkusu) and describes the attraction to young boys. It refers to a genre of [[manga]] and [[anime]] wherein pre-pubescent or pubescent male characters are depicted in a suggestive or erotic manner, whether in the obvious role as the object of attraction, or the less apparent role of "subject" (the character the reader is designed to associate with), as in when the young male character is paired with a male, usually in a homoerotic manner. The term shota is a westernized abbreviation for shotacon. | |||

'''[[Manga_and_anime#Shotacon|Shotacon]]''' ショタコン is | |||

{{clr}} | {{clr}} | ||

== Cinema == | == Cinema == | ||

* Shima | *Shima Kōji (島 耕二) (1901-1986) : ''[[Maboroshi no uma (Shima Kōji)|Maboroshi no uma]]'' (幻の馬) (''Horse and the child''), 1955. | ||

* Gosho | *Gosho Heinosuke (五所 平之助) (1902-1981) : ''[[Jinsei no onimotsu (Gosho Heinosuke)|Jinsei no onimotsu]]'' (人生のお荷物) (''The burden of life''), 1935. | ||

* [[Ozu | *[[Ozu Yasujirō]] (小津 安二郎) (1903–1963) : ''[[Otona no miru ehon – Umarete wa mita keredo (Ozu Yasujirō)|Otona no miru ehon – Umarete wa mita keredo]]'' (大人の見る絵本 生れてはみたけれど) (''I saw I was being born, but ...'' = ''Yet we are born'' = ''Kids of Tokyo''), 1932 ; ''[[Deligokoro (Ozu Yasujirō)|Deligokoro]]'' (出来ごころ) (''Capricious heart''), 1933 ; ''[[Tōkyō no yado (Ozu Yasujirō)|Tōkyō no yado]]'' (東京の宿) (''An Inn in Tokyo''), 1935 ; ''[[Nagaya shinshiroku (Ozu Yasujirō)|Nagaya shinshiroku]]'' (長屋紳士録) (''Record of a Tenement''), 1947 ; ''[[Ohayō (Ozu Yasujirō)|Ohayō]]'' (お早よう) (''Good morning''), 1959. | ||

* Shimizu | *Shimizu Hiroshi (清水 宏) (1903-1966) : ''[[Kaze no naka no kodomo (Shimizu Hiroshi)|Kaze no naka no kodomo]]'' (風の中の子供) (''Children within the wind''), 1937 ; ''[[Hachi no su no kodomotachi (Shimizu Hiroshi)|Hachi no su no kodomotachi]]'' (蜂の巣の子供たち) (''Children of the honeycomb''), 1948. | ||

* Hiroshi | *Inagaki Hiroshi (稲垣 浩) (1905-1980) : ''[[Muhōmatsu no isshō (Inagaki Hiroshi)|Muhōmatsu no isshō]]'' (無法松の一生) (''The rickshaw''), 1958. | ||

* Kinoshita | *Kinoshita Keisuke (木下 惠介) (1912-1998) : ''[[Nijū-shi no hitomi (Kinoshita Keisuke)|Nijū-shi no hitomi]]'' (二十四の瞳) (''Twenty-Four Eyes''), 1954. | ||

* | *Shindō Kaneto (1912-2012) : ''[[Genbaku no ko (Shindō Kaneto)|Genbaku no ko]]'' (原爆の子) (''Children of Hiroshima''), 1952; ''[[Hadaka no shima (Shindō Kaneto)|Hadaka no shima]]'' (裸の島) (''Naked island''), 1961. | ||

* Nagisa | *Ōshima Nagisa (大島 渚) (1932-2013) : ''[[Shōnen (Ōshima Nagisa)|Shōnen]]'' (少年) (''The boy''), 1969. | ||

* [[Terayama | *[[Terayama Shūji]] (寺山 修司) (1935-1983) : ''[[Tomato Kecchappu Kōtei (Terayama Shūji)|Tomato Kecchappu Kōtei]]'' (トマトケチャップ皇帝) (''The Emperor Tomato Ketchup''), 1971 in censored version, 1996 in full version ; ''[[Den’en ni shisu (Terayama Shūji)|Den’en ni shisu]]'' (田園に死す) (''Pastoral Hide and Seek''), 1974. | ||

* | *Gotō Toshio (後藤 俊夫) (born 1938) : ''[[Matagi (Gotō Toshio)|Matagi]]'' (マタギ) (''Matagi the old bear hunter''), 1982. | ||

* Oguri | *Oguri Kōhei (小栗 康平) (born 1945) : ''[[Doro no kawa (Oguri Kōhei)|Doro no kawa]]'' (''River of mud''), 1981. | ||

* Kore-eda Hirokazu (born | *Kore-eda Hirokazu (born 1962) : ''[[Dare mo shiranai (Kore-eda Hirokazu)|Dare mo shiranai]]'' (誰も知らない) (''Nobody knows''), 2004; ''[[Kiseki (Kore-eda Hirokazu)|Kiseki]]'' (奇跡) (''I wish'' = ''I wish our secret wishes ''), 2011. | ||

=== Erotic videos === | === Erotic videos === | ||

In the 1990s were produced in Japan VHS | In the 1990s professional-quality videos featuring juvenile eroticism were produced in Japan in VHS format. They usually showed teenage boys and pre-teens in a very carefully done and fairly slow style. At the end of each video were often given the names of the young actors, their ages and measurements. | ||

== Personalities and foreign works related to Japan == | == Personalities and foreign works related to Japan == | ||

* | *Karl Kliest, born in Beijing in 1931, died in New South Wales in 1976, whose Japanese childhood is told in Paedomorphs I: the story of a young boy in pre-war Japan. <ref>Nigel Downsbrough, Paedomorphs I : the story of a young boy in pre-war Japan, Taipei, Kiryudo Publishing Co., 1978.</ref> | ||

== Citations == | == Citations == | ||

They were wonderful stories of small pages loving | They were wonderful stories of small pages loving old nobility and threatening to do harakiri if the noble old did not accept their advances; priests selling the relics of their temples to maintain acolytes; samurai who were begging to track,from province to province, another cute samurai. | ||

* [[Roger Peyrefitte]], The exile of Capri , Paris, Le Livre de Poche (Pocket book), 1974 Part Three, chap. III, p. 260-261 <ref>L’exilé de Capri / [[Roger Peyrefitte]] ; couv. [[Gaston Goor]]. – Éd. définitive. – Paris : Le Livre de Poche, 1974 (La Flèche : Brodard et Taupin, 25 novembre 1974). – 331-[21] p. : couv. ill. en coul. ; 17 × 11 cm. – (Le livre de poche ; 3912). (fr) ISBN 2-253-00119-8</ref> | |||

* Roger Peyrefitte, | |||

== Notes and references == | |||

{{reflist|3}} | |||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

| Line 284: | Line 219: | ||

{{Mediaboywiki|Category:Nippon|titre=les arts du Japon}} | {{Mediaboywiki|Category:Nippon|titre=les arts du Japon}} | ||

* [[ | * [[Historical boylove relationships in Japan]] | ||

* [[Bishōnen]] | |||

* [[Chigo]] | * [[Chigo]] | ||

* [[Chigo | * [[Chigo monogatari]] | ||

* [[ | * [[Historical boylove relationships in Japan]] | ||

* [[Nanshoku Okagami (Ihara Saikaku)]] ''(The Great Mirror of Male Love:The Custom of Boy Love in Our Land)'' | |||

* [[Nanshoku Okagami (Ihara Saikaku)]] ''(The | |||

* [[Samurai]] | * [[Samurai]] | ||

* [[ | * [[Shōnen]] | ||

* [[Shota]] | * [[Shota]] | ||

* [[ | * [[Shudô]] | ||

* [[ | * [[Wakashū]] | ||

* [[ | * [[Wakashudō]] | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

* Manfred Lesgourgues conference during | * Manfred Lesgourgues conference during the Japan Week ENS, recorded by France-Culture April 28, 2011: "[[nanshoku: pederasty samurai]]." | ||

*Google translator (works very well to very poorly, depending on the language skills of the original author, and on the languages being translated): | |||

:https://translate.google.com | |||

{{ | *The "untouchable" class in Japan, similar to that in India: | ||

:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burakumin | |||

*The Ainu, the native ethnic group originally inhabiting Japan before the Mongoloid settlements. | |||

:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ainu | |||

*The "Meiji restoration" which brought much Western influence to Japan: | |||

:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meiji_restoration | |||

*Regarding a film mentioned abouve: | |||

:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurosawa | |||

:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kagemusha | |||

*Regarding the Japanese adoption and adaptation of the German legal system: | |||

:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foreign_government_advisors_in_Meiji_Japan | |||

{{Navbox Japan|collapsed}} | |||

[[fr:Japon]] | [[fr:Japon]] | ||

[[Category:Japan]] | [[Category:Japan]] | ||

Latest revision as of 08:59, 18 August 2021

| Part of the boylove history series |

|

| Portal:History |

Japan (in Japanese, Nippon or Nihon -- 日本) is an island nation located east of China, Korea and Russia, which was originally inhabited by fishermen belonging to the Ainu (アイヌ) peoples (who today represent no more than about 1 percent of the total population) but now populated almost entirely by Mongoloid immigrants from the mainland Asian land mass, immigration which occurred in two distinct waves during the Japanese prehistoric period. About 0.5% of the residents of Japan are of Korean descent -- often the children of workers from the time Japan forcefully annexed Korea (1910-1945), who, while born in Japan, have had their nationality hotly contested by other native-born Japanese nationals. About 0.4% of the population are Chinese, and 0.6% "other".

In terms of language and customs, Japanese civilization has been very strongly influenced by neighboring countries (China, Korea, and India) as well as by the distant cultures (beginning in the Meiji restoration [1868]) of Europe and the USA, while trying at the same time to preserve its unique characteristics. For example, Japanese cuisine is largely of native origin, though Chinese-style dishes are quite popular as well.

Japan remained closed to Western influence for over two centuries, from 1641 to 1853, after having expelled the Christian missionaries, as well as most other foreigners, and severely limiting external trade. However, in 1853 it was forced to open up its borders by threats of military attack made by the US war fleet commanded by Commodore Matthew Perry which was sent by President Millard Fillmore to open Japan to trade, by whatever means possible, including acts of war.[1] This was the beginning of the end of normal and healthy BoyLove in Japan.

The wakashudō, , also called nanshoku, describes a social, emotional and sexual relationship formed between an adult male and a young boy. Existing since at least the eighth century and popular until the nineteenth, it is the most durable pederastic institution attested to in the history of mankind.

Notes on Japanese social patterns

Confucianism is almost universally practiced, along with Buddhism. The Confucian social order in Japan, from highest to lowest class, is the samurai (warriors), the farmers and artisans, the traders and businessmen, and, finally, the Burakumin (the outcasts, very similar to the "untouchable" class in the Indian Hindu system of social stratification).

However, aside from the treatment of those descendants of the Burakumin class, the social structure usually gives greater weight to differences in age rather than to social status.

Japanese culture places a lot of emphasis on respecting those who are older than ones self. Elderly persons are treated with the utmost respect, even to the point of having their own holiday, Keiro no Hi, or "Respect for the Aged Day". [1] This may be because of the Shinto belief that things accrue power as they become older.

At the same time, children in Japan also have their own days: Kodomo no Hi, also called "Boy's Day" or "Children's day", Hinamatsuri, also called "Girl's Day" or "Doll's Day", and "7-5-3 Day", a day to celebrate children aged 7, 5, and 3. [2] [3][4]

There are no Japanese taboos regarding anal sex (human excrement has not, at least, traditionally, been seen as some kind of "dirty" waste, but rather as a natural fertilizer recycled for use in fertilizing crops growing in the fields). Anal intercourse, not being seen as "disgusting" or "dirty" as in the West, was therefore not stigmatized except for any possible pain it might cause the passive partner. Also, the the passive role in anal intercourse was not seen as being something demeaning nor feminizing, as it tended to be in Western Greek homosexuality.

It should be noted in this regard that the chrysanthemum flower is both the symbol of the Emperor, and of the anus in nanshoku.

Nanshoku and wakashudō

In the pre-modern period, there were two distinct terms used to describe the Japanese form of pederasty:

- nanshoku (男色) (alternate reading, danshoku) signifies "manly lust" or "lust between males". It refers to pederastic or homosexual sexual practices. See [5]

- wakashudō (若衆道) consists of the character dō (道), adapted from the Chinese character "tao" meaning "the path" (along which we progress); and the term wakashū (若衆), "young person" or more specifically, "boy": the term wakashudō literally means "the way of the boys."

It may also take the abbreviated forms shudō (衆道) and nyakudō (若道).

- Similarly, we find the term bidō (美道); the "beautiful way".

In brief, nanshoku evokes the concepts of pleasure, passion, and virility; while wakashudō focuses more on the young boy's guided pursuit of knowledge and wisdom.

The wakashū (young boys) involved in wakashudō relationships belonged to a well-defined age group, whose boundaries could vary from five to twenty-five years of age, though the most appropriate ages were often considered to be from fourteen to eighteen. Note, however, that puberty probably occurred later than it does today in Japan, and, furthermore, the relative lack of body hair of the Japanese may give them a longer-lasting youthful appearance than their European counterparts.

Religions

Religion in Japan consists mainly of the animistic Shinto belief system and Buddhism. These beliefs are tempered with Chinese Confucianism. Christians now account for about 2% of the population, while Islam is virtually nonexistent.

There are no sexual taboos in Shintoism, which considers sexual activity to be an absolute pleasure, as does Confucianism as well.

In Buddhism, each monk takes vows to forsake all sexual thoughts involving women. While total sexual abstinence is seen as preferable, sexual activity with males is seen as a last resort to satiate the inevitable desire for sexual activity.

Taoism, which strongly influences Japanese Zen Buddhism, emphasizes balance. Taoism holds that heterosexual activity in humans involves a catastrophic loss of energy, and therefore should be moderated. This risk does not exist in the case of homosexual sex.

None of these religious or philosophical practices considers pederasty or homosexuality as being unnatural.

Shinto deities

During the Tokugawa shogunate (from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries), many Shinto gods were considered to be the guardian deities of nanshoku, in particular, Hachiman (八幡神), Myoshin, Shinmei and Tenjin (天神). Also evoked was Hotei (布袋) ("Budai" in China), the "laughing Buddha," often surrounded by beautiful and reverent boys.

The writer Ihara Saikaku jokingly says that, because there are no women in the first three generations of the divine genealogy described in Nihon shoki (日本書紀) ("The Chronicles of Japan"), the gods have always engaged in sexual activity - and he considers this as the true origin of nanshoku. [2]

Buddhist deities

Buddhism was imported from China beginning in the fifth century, eventually evolving in Japan into thirteen major schools. It gained particular importance during the Nara period (8th century AD).

Monju (文殊) or Monjushiri (文殊師利) is the Japanese name for Mañjuśrī, the great bodhisattva [3] of wisdom. However, according to later traditions, this deity would be the originator of nanshoku. [4] It should be noted that one of the deities names in Sanskrit is Mañjuśrī Kumārabhūta ("The Youth"), which, in Chinese, may also be called Rǔtóng wénshū (孺童文殊) "the young child Wenshu," or Fǎwángzǐ (法王子) "the Son of the Buddha."

Spiritual Masters

Despite the fact that in some cultures the local form of Buddhism adhered to may object to some extent to homosexual practices, male homosexuality in Japan is closely associated with Japanese Buddhist institutions.

The Buddhist monk Kūkai (空海), also known as Kōbō-Daishi (弘法大師) (774-835), was the founder of the tantric branch of Shingon Buddhism (真言), as well as an important monastic community. He is said to have introduced pederasty to Japan on his return from China in 806; but some consider that his reputation for having done so was either initially created, or later exaggerated, by the Christian missionary Francis Xavier. Mount Kōya (高野山), the name which also refers to the monastery founded there by Kūkai, was commonly used until the end of the pre-modern era in Japan to refer to pederastic relationships.

History

The beginnings of nanshoku

No sources mention the possible existence in ancient times of pederastic practices in Japan.

Several descriptions of homosexual acts exist in ancient literary works, but most are too subtle to be established unambiguously; displays of physical affection between same sex couples were common and accepted at that time. The first sources citing pederastic relationships date back to the Heian period, around the eleventh century.

In The Tale of Genji (源氏物語) written around that time, men are often shown to be attracted to the beauty of young boys. One scene shows, for example, the hero being rejected by a woman, and then later sleeping with the little brother of the woman instead:

| “ | Well, at least you will never abandon me." Genji pulled the boy next to him so they would sleep together. The boy was delighted, as was Genji with the boy's juvenile charms. Genji said, for his part, that he found the boy more attractive than his frigid sister. |

” |

The Tale of Genji is, of course, only a novel, but some other accounts from the same era and until the first half of the fourteenth century, also contain descriptions of pederasty activities. Some of them even implicate emperors as having been involved in relationships with "beautiful boys for sexual purposes". [5] But they did not give rise to any pederastic tradition, unlike what occurred in China in antiquity.

The era of the founding of monasteries

Monastic communities began to be founded beginning in the ninth century. By the end of the sixteenth century, the number amounted to about ninety thousand. Some were home to a thousand men and boys, and the largest up to three thousand. Monks would keep as novices children or teenagers called chigo (稚児). These young people, often from large families, came to learn the Buddhist liturgy, or to prepare themselves for a monastic career.

Sexual relationships between a monk and a chigo were common. They included anal sex. Each partner was given a name and took a specific role: the elder (nenja (念者) -- the lover, admirer -- nenyū, anibun, anikibun, kyūkyū) and the youth (wakashū [若衆] - young person -- nyake, otōtobun) contracted a fraternal liaison (kyōdai keiyaku or kyōdai chigiri) and swore loyalty to each other.

In 1419 and 1436, a ban was placed on the monks: Not a ban on having sexual relations with their novices, but a ban on dressing them as girls. However, it was expected that these boys would one day became men, and that their female costumes were meant to be purely aesthetic and erotic, and not meant to feminize their behavior.

European observations

The first Europeans visitors to Japan were shocked by the frequency and openness of pederastic relationships. The Portuguese Jesuit Alessandro Valignani, observed in 1591:

| “ | Young boys and their partners do not consider the matter as something serious, neither do they hide what they do. In fact, they see what they do as being honorable, and speak openly about it. Not only do they not take the doctrine of the monks as being something wrong, they themselves practice this custom, holding it to be absolutely natural and, at the same time, something virtuous. | ” |

The age of the samurai

The age of the samurai began in the eighth century, at the end of the Nara period, [6] when the first professional warriors appeared; young cavalry archers from affluent backgrounds. They formed a militia of 3964 men, who later led to the formation of the samurai caste in the tenth century.

Numerous samurai first became novices in a monastery. Monastic morals therefore came to be used as models for male love, the model for those males who lived with warriors. The feudal structure of society contributed in the same way in structuring these relationships.

As between a monk and a novice, the relationship between two samurai begins with fraternal oaths, possibly in writing, which then constituted a genuine contract (in these cases, the relationship would be monogamous). Many of these contractual oaths have been preserved, including that between Takeda Shingen (best known in the West as the central protagonist of Kagemusha in the Kurosawa film of the same name) and his lover, Dansuke Kasuga, then aged twenty-two and sixteen years, respectively.

Unlike ancient Greek pederasty, the initiative to start such a relationship fell on the boy. But as the samurai apprentice was often very young, between ten and thirteen years of age when initiated in wakashudō -- it may have been the parent who usually sought out a master for the boy.

The young samurai served his elder during military campaigns. In peacetime, he often would act the part of a page to the older partner, and be considered to possess feminine allures.

Wakashudō principles are part of a rich literary tradition; we find mentions in works such as Hagakure or in various manuals written for the samurai. In its educational, military and aristocratic aspects, the wakashudō tradition strongly resembled the ancient Greek pederastic tradition.

This practice was held in very high regard and saw encouragement among the samurai . It was considered beneficial for the boy in that it taught the boy virtue, honesty and a sense of beauty. The love of women, in contrast, was thought to feminize men.

| “ | The nanshoku is the leisure of the Samurai: how could it be detrimental to good government? [7] | ” |

Traditions artificially corrupted

From the seventeenth century, as the samurai were being inspired by the nanshoku practiced by monks, the bourgeois merchant class began to imitate the man-boy loves of the samurai, but adapting them according to their own principles.

The values of love and honor that previously prevailed were then gradually replaced by those of simple pleasure and money. The educational aspects gave way to prostitution , the manhood to effeminacy. In return, the moral degradation eventually came to contaminate the Samurai monastic classes.

Prostitution

During the Edo period (1600-1868) the onnagata, as were called the boy or young male actors who interpreted adult female roles on stage in kabuki theatre, also often worked on the side as prostitutes.

The KAGEMA were male prostitutes working in specialized brothels, the kagemajaya (陰間茶屋) called "KAGEMA"tea houses. In the nineteenth century there existed twenty-four red light districts for boy prostitution in Tokyo.

Both the KAGEMA and the onnagata were prized by refined followers of nanshoku. A male prostitute could be paid much more than an expensive female prostitute: An expensive female prostitute could receive 5 monme for one tryst, while a boy could be valued at between 43 and 129 monme for the same.[8]

Modern Japan

With the beginnings of the Meiji Restoration and the growing influence -- and the wholesale importation -- of facets of Western cultures (and the founding of a legal system based on the German model), all homoerotic practices, including wakashudō, began to be subject to criminal sanctions and to rapid decline in the late nineteenth century.

Man-boy sex

- IMPORTANT NOTE: Laws regarding intergenerational sexual relationships can change quickly, and new penalties may be draconian. The following should not be taken as legal advice!***

The minimum legal age for sexual relations between men and boys is set differently in the forty seven different prefectures (or departments) in Japan. However, the "centralized" legislation passed by the Japanese Diet takes primacy over local laws. But if the trial courts apply the local laws, the appellate courts must follow the centralized law.

This somewhat complex system, which is partly dependent on local features, could result in a man being condemned in some prefectures for having sex with a boy of fourteen. But if he appeals his case - which is in his best interest - it will be decided according to the centralized law, which permits adult-minor relationships from thirteen years of age: He will then eventually be acquitted.

Erotic materials

Real and virtual pornography

The production, distribution and possession of child pornography is prohibited in Japan if it involves actual minors.

In June 2014, the simple possession of such images became a crime punishable with imprisonment of up to a year, and a fine of up to one million yen. However, a one-year period to come into compliance with the new law was provided for.

Imaginary representations (drawings, etc.) which do not involve images of real children are still legal.

Literature

- Several anonymous chigo monogatari tell of the love of monks for their young novices.

- Ihara Saikaku [9] (井原 西鶴) or Saikaku (1642-1693): nanshoku Okagami (男色大鏡) (The Great Mirror of Male Love), 1689.

Fine Arts

Shunga

Shunga (春画) is a Japanese term for erotic art. Most shunga are a type of ukiyo-e, usually executed in woodblock print format. While rare, there still exist erotic painted handscrolls which predate the Ukiyo-e movement.[10] Translated literally, the Japanese word shunga means picture of spring; "spring" being a common euphemism for sex.

Manga

Manga (漫画) are comics created in Japan, or by those creating comics in the Japanese language, conforming to a style developed in Japan in the late 19th century.[11] They have a long and complex pre-history in earlier Japanese art. [12]

Shotacon

Shotacon (ショタコン) is Japanese slang. It is a portmanteau of the phrase, "Shōtarō complex" (正太郎コンプレックス = shōtarō konpurekkusu) and describes the attraction to young boys. It refers to a genre of manga and anime wherein pre-pubescent or pubescent male characters are depicted in a suggestive or erotic manner, whether in the obvious role as the object of attraction, or the less apparent role of "subject" (the character the reader is designed to associate with), as in when the young male character is paired with a male, usually in a homoerotic manner. The term shota is a westernized abbreviation for shotacon.

Cinema

- Shima Kōji (島 耕二) (1901-1986) : Maboroshi no uma (幻の馬) (Horse and the child), 1955.

- Gosho Heinosuke (五所 平之助) (1902-1981) : Jinsei no onimotsu (人生のお荷物) (The burden of life), 1935.

- Ozu Yasujirō (小津 安二郎) (1903–1963) : Otona no miru ehon – Umarete wa mita keredo (大人の見る絵本 生れてはみたけれど) (I saw I was being born, but ... = Yet we are born = Kids of Tokyo), 1932 ; Deligokoro (出来ごころ) (Capricious heart), 1933 ; Tōkyō no yado (東京の宿) (An Inn in Tokyo), 1935 ; Nagaya shinshiroku (長屋紳士録) (Record of a Tenement), 1947 ; Ohayō (お早よう) (Good morning), 1959.

- Shimizu Hiroshi (清水 宏) (1903-1966) : Kaze no naka no kodomo (風の中の子供) (Children within the wind), 1937 ; Hachi no su no kodomotachi (蜂の巣の子供たち) (Children of the honeycomb), 1948.

- Inagaki Hiroshi (稲垣 浩) (1905-1980) : Muhōmatsu no isshō (無法松の一生) (The rickshaw), 1958.

- Kinoshita Keisuke (木下 惠介) (1912-1998) : Nijū-shi no hitomi (二十四の瞳) (Twenty-Four Eyes), 1954.

- Shindō Kaneto (1912-2012) : Genbaku no ko (原爆の子) (Children of Hiroshima), 1952; Hadaka no shima (裸の島) (Naked island), 1961.

- Ōshima Nagisa (大島 渚) (1932-2013) : Shōnen (少年) (The boy), 1969.

- Terayama Shūji (寺山 修司) (1935-1983) : Tomato Kecchappu Kōtei (トマトケチャップ皇帝) (The Emperor Tomato Ketchup), 1971 in censored version, 1996 in full version ; Den’en ni shisu (田園に死す) (Pastoral Hide and Seek), 1974.

- Gotō Toshio (後藤 俊夫) (born 1938) : Matagi (マタギ) (Matagi the old bear hunter), 1982.

- Oguri Kōhei (小栗 康平) (born 1945) : Doro no kawa (River of mud), 1981.

- Kore-eda Hirokazu (born 1962) : Dare mo shiranai (誰も知らない) (Nobody knows), 2004; Kiseki (奇跡) (I wish = I wish our secret wishes ), 2011.

Erotic videos

In the 1990s professional-quality videos featuring juvenile eroticism were produced in Japan in VHS format. They usually showed teenage boys and pre-teens in a very carefully done and fairly slow style. At the end of each video were often given the names of the young actors, their ages and measurements.

- Karl Kliest, born in Beijing in 1931, died in New South Wales in 1976, whose Japanese childhood is told in Paedomorphs I: the story of a young boy in pre-war Japan. [13]

Citations

They were wonderful stories of small pages loving old nobility and threatening to do harakiri if the noble old did not accept their advances; priests selling the relics of their temples to maintain acolytes; samurai who were begging to track,from province to province, another cute samurai.

- Roger Peyrefitte, The exile of Capri , Paris, Le Livre de Poche (Pocket book), 1974 Part Three, chap. III, p. 260-261 [14]

Notes and references

- ↑ Commodore Perry's expedition to force an "opening up" of Japan to trade with Western countries: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perry_Expedition

- ↑ Gary P. Leupp, Male colors : the construction of homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan, University of California Press, 1999, ISBN 0-520-20909-5, p. 32-34.

- ↑ A bodhisattva can be defined as an "active saint" after reaching perfection, he deferred his entry into nirvana to help all beings find their deliverance.

- ↑ Louis Crompton, Homosexuality and civilization, Cambridge (Massachusetts), Harvard University Press, 2003, p. 413f.

- ↑ Gary P. Leupp, Male colors : the construction of homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan, University of California Press, 1999, ISBN 0-520-20909-5, p. 26.

- ↑ At that time it was also decided that no woman would be allowed to ascend to the throne, because of their excessive tendency to "devotion"???MUST CHECK???. The ban would remain in effect for nearly a thousand years.

- ↑ Eijima Kiseiki, Huhwan meishu kenshō, XVIIe siècle. [The orthography and title of this still requires verification]

- ↑ The monme is an ancient Japanese unit of weight and measure equivalent to 3.75 grams of silver. For comparison, the annual salary of a servant to a wealthy family was about 240 monme.

- ↑ Parfois transcrit Saïkakou Ebara.

- ↑ (in Finnish) Forbidden Images – Erotic art from Japan's Edo Period. Helsinki, Finland: Helsinki City Art Museum. 2002. pp. 23–28. ISBN 951-8965-53-6.

- ↑ Lent 2001, pp. 3–4, Gravett 2004, p. 8

- ↑ Kern 2006, Ito 2005, Schodt 1986

- ↑ Nigel Downsbrough, Paedomorphs I : the story of a young boy in pre-war Japan, Taipei, Kiryudo Publishing Co., 1978.

- ↑ L’exilé de Capri / Roger Peyrefitte ; couv. Gaston Goor. – Éd. définitive. – Paris : Le Livre de Poche, 1974 (La Flèche : Brodard et Taupin, 25 novembre 1974). – 331-[21] p. : couv. ill. en coul. ; 17 × 11 cm. – (Le livre de poche ; 3912). (fr) ISBN 2-253-00119-8

See also

Bibliography

- Downsbrough Nigel Paedomorphs. I: the story of a young boy in pre-war Japan. - Taipei: Kiryudo Publishing Co., 1978.

- "Nanshoku: male-male eroticism in Japan", in Koinos Magazine , nr 40 (April 2003) and nr 41 (January 2004).

- Pflugfelder, Gregory M. Cartographies of desire: male-male sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600-1950. - Berkerley: University of California Press, 2000.

- [Ihara Saikaku] Saïkakou Ebara. Tales of love samurai / trans. Ken Sato; Patrick Raynaud drawings. - Jacques Damase, 1981. 7 stories of samurai and 4 stories of actors, from the glorious stories of pederasty, Stories of the samurai spirit Stories duties of samurai and letters in Stories.

- Ihara Saikaku. Amours samurai / trans. Japanese and presented by Gérard Siary; with the collab. Mieko Nakajima-Siary. - Arles: Philippe Picquier 1999 (Aubenas Print Lienhart.). - 250 p. : Ill., Cov. Fig. col. ; 21 cm. - (The great mirror of male love: love custom boy in our country; 1) (Pavilion curious body ISSN 1274-9508). Trad. of the 1st part: nanshoku Okagami. - Includes bibliographical references. p. 59-65. - ISBN 2-87730-451-5 (br.)

- Ihara Saikaku. Amours actors / trans. Japanese and presented by Gérard Siary; with the collab. Mieko Nakajima-Siary. - Arles: Philippe Picquier, 2000 (Gemenos Print Robert.). - 217 p. : Map, cov. Fig. col. ; 21 cm. - (The great mirror of male love: love custom boy in our country, 2) (Pavilion curious body ISSN 1274-9508). Trad. the 2nd part: nanshoku Okagami. - Glossary. - ISBN 2-87730-469-8 (br.)

- Tsuneo Watanabe, Jun'ichi Iwata The way of youths. History and stories of homosexuality in Japan. - Ed. Trismegistus, 1987. - (Eastern Sexuality) ( ISBN 2-86509-024-8 )

Related articles

Media-BoyWiki

has media related to

Japan

- Historical boylove relationships in Japan

- Bishōnen

- Chigo

- Chigo monogatari

- Historical boylove relationships in Japan

- Nanshoku Okagami (Ihara Saikaku) (The Great Mirror of Male Love:The Custom of Boy Love in Our Land)

- Samurai

- Shōnen

- Shota

- Shudô

- Wakashū

- Wakashudō

External links

- Manfred Lesgourgues conference during the Japan Week ENS, recorded by France-Culture April 28, 2011: "nanshoku: pederasty samurai."

- Google translator (works very well to very poorly, depending on the language skills of the original author, and on the languages being translated):

- The "untouchable" class in Japan, similar to that in India:

- The Ainu, the native ethnic group originally inhabiting Japan before the Mongoloid settlements.

- The "Meiji restoration" which brought much Western influence to Japan:

- Regarding a film mentioned abouve:

- Regarding the Japanese adoption and adaptation of the German legal system: