Theban pederasty: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

In [[ | In [[Thebes]], the main polis in [[Boeotia]], a renowned center of [[Pederasty in ancient Greece|pederasty]], the practice was enshrined in the [[founding myth]] of the city. In this instance the story was meant to teach by counterexample: it depicts [[Laius]], a divine hero and one of the mythical ancestors of the Thebans, in the role of a lover who betrays the father and rapes the son, [[Chrysippus (mythology)|Chrysippus]]. For his double crime the gods meted out exemplary punishment, visited not only upon him, but upon his own son, [[Oedipus]], and his children. (In an apparent attempt to emphasize Laius' criminality, ancient artistic convention had his victim depicted not as an adolescent – the usual representation of beloved boys in Greek paintings on ceramic – but as a child, a reference to the contempt the Greeks had for men who pursued under-age boys). The tale of Laius and Chrysippus garnered Thebes the distinction of being, on the mainland, the "legendary font of Greek pederasty."<ref>William A. Percy, ''Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece,'' 1996; p.133</ref> | ||

Another Boeotian pederastic myth is the story of the hero [[Narcissus (mythology)|Narcissus]] of [[Thespiae]], a tale which, in its archaic form, was a cautionary myth teaching boys not to be cruel to their lovers. | Another Boeotian pederastic myth is the story of the hero [[Narcissus (mythology)|Narcissus]] of [[Thespiae]], a tale which, in its archaic form, was a cautionary myth teaching boys not to be cruel to their lovers. | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

Towards the end of the Classical period of Theban history, [[Gorgidas]], a renowned statesman and general formed a military battalion consisting of one hundred and fifty pairs of men with their youthful lovers, known as the [[Sacred Band of Thebes]], which had the reputation of being unbeatable until they fell in battle against [[Philip II of Macedon|Philip II]] at [[Chaeronea]] in [[338 BCE]]. | Towards the end of the Classical period of Theban history, [[Gorgidas]], a renowned statesman and general formed a military battalion consisting of one hundred and fifty pairs of men with their youthful lovers, known as the [[Sacred Band of Thebes]], which had the reputation of being unbeatable until they fell in battle against [[Philip II of Macedon|Philip II]] at [[Chaeronea]] in [[338 BCE]]. | ||

Contemporary (mostly Athenian) sources seem to indicate that pederasty in Thebes was freer than in other cities - indeed, unfettered - often referring to the Thebans as "Boeotian swine" for their rural ways.<ref>Pindar, ''Olympian Ode VI''</ref><ref>Plutarch, ''Moralia,'' 995</ref> In Plato's [[Symposium (Plato)|''Symposium'']], the character Pausanias explains that the Theban rules encourage boys to satisfy their lovers sexually, so as to save the men the bother of convincing the youths - allegedly more difficult for Thebans on account of their poor speaking skills. The comic and philosophical contexts of Plato's work, however, must be taken into account when considering the historical veracity of this claim.<ref>Plato, ''Symposium,'' 182 b1-b6</ref> Modern comparative studies suggest that this picture of Theban pederasty is inaccurate, a result of nationalist and xenophobic attitudes on the part of the writers.<ref> | Contemporary (mostly Athenian) sources seem to indicate that pederasty in Thebes was freer than in other cities - indeed, unfettered - often referring to the Thebans as "Boeotian swine" for their rural ways.<ref>Pindar, ''Olympian Ode VI''</ref><ref>Plutarch, ''Moralia,'' 995</ref> In Plato's [[Symposium (Plato)|''Symposium'']], the character Pausanias explains that the Theban rules encourage boys to satisfy their lovers sexually, so as to save the men the bother of convincing the youths - allegedly more difficult for Thebans on account of their poor speaking skills. The comic and philosophical contexts of Plato's work, however, must be taken into account when considering the historical veracity of this claim.<ref>Plato, ''Symposium,'' 182 b1-b6</ref> Modern comparative studies suggest that this picture of Theban pederasty is inaccurate, a result of nationalist and xenophobic attitudes on the part of the writers.<ref>Hupperts Charles, ''Boeotian Swine Homosexuality in Boeotia'', Journal of Homosexuality, volume 49, pp.173–192, publisher Haworth Press</ref> | ||

[[Pindar]], a Theban poet who is one of the few primary sources on Theban pederasty, presents a more conventional view, in which athletics and sexual desire are closely linked. Likewise, the ceramic paintings seem to depict a range of practices similar to those shown on vases from [[Athens]] and [[Corinth]]. <ref>"Boeotian Swine: Homosexuality in Boeotia," by Charles Hupperts, in ''Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West,'' ed. B. C. Verstraete and V. Provencal, Harrington Park Press, 2005, pp.180-190</ref> | [[Pindar]], a Theban poet who is one of the few primary sources on Theban pederasty, presents a more conventional view, in which athletics and sexual desire are closely linked. Likewise, the ceramic paintings seem to depict a range of practices similar to those shown on vases from [[Athens]] and [[Corinth]]. <ref>"Boeotian Swine: Homosexuality in Boeotia," by Charles Hupperts, in ''Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West,'' ed. B. C. Verstraete and V. Provencal, Harrington Park Press, 2005, pp.180-190</ref> | ||

==Famous lovers== | ==Famous lovers== | ||

| Line 64: | Line 34: | ||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}} | ||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

*[[Ancient Greece]] | *[[Ancient Greece]] | ||

*[[Harmodius and Aristogeiton]] | |||

*[[Pederasty]] | *[[Pederasty]] | ||

*[[Pederasty in ancient Greece]] | *[[Pederasty in ancient Greece]] | ||

*[[Philosophy of ancient Greek pederasty]] | |||

*[[Symposium]] | *[[Symposium]] | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 99: | Line 60: | ||

*"Boeotian Swine: Homosexuality in Boeotia," by Charles Hupperts, in ''Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West,'' ed. B. C. Verstraete and V. Provencal, Harrington Park Press, 2005, pp.173-192 | *"Boeotian Swine: Homosexuality in Boeotia," by Charles Hupperts, in ''Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West,'' ed. B. C. Verstraete and V. Provencal, Harrington Park Press, 2005, pp.173-192 | ||

{{Navbox Pederasty|collapsed}} | |||

{{Navbox Ancient Greece}} | |||

[[Category:Ancient Greece]] | [[Category:Ancient Greece]] | ||

Latest revision as of 22:52, 2 July 2022

| Part of the boylove history series |

|

| Portal:History |

Theban pederasty was a social institution by means of which upper class Theban adolescent boys were educated and entered into adult responsibilities through a love and sexual relationship with an adult aristocrat. It is thought to have either been introduced at the time of the original Dorian invasion, around 1200 BCE, or in late Archaic times, shortly after 630 BCE, the time of its introduction in Ancient Crete according to another theory.

The custom was reflected in the religion, as indicated by the many myths with pederastic themes. It also was integral to the military life of the city, both in the training of warriors and in the prosecution of war.

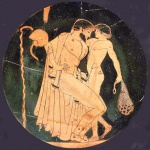

Mythology

In Thebes, the main polis in Boeotia, a renowned center of pederasty, the practice was enshrined in the founding myth of the city. In this instance the story was meant to teach by counterexample: it depicts Laius, a divine hero and one of the mythical ancestors of the Thebans, in the role of a lover who betrays the father and rapes the son, Chrysippus. For his double crime the gods meted out exemplary punishment, visited not only upon him, but upon his own son, Oedipus, and his children. (In an apparent attempt to emphasize Laius' criminality, ancient artistic convention had his victim depicted not as an adolescent – the usual representation of beloved boys in Greek paintings on ceramic – but as a child, a reference to the contempt the Greeks had for men who pursued under-age boys). The tale of Laius and Chrysippus garnered Thebes the distinction of being, on the mainland, the "legendary font of Greek pederasty."[1]

Another Boeotian pederastic myth is the story of the hero Narcissus of Thespiae, a tale which, in its archaic form, was a cautionary myth teaching boys not to be cruel to their lovers.

Iolaus was another pederastic hero honored in Thebes. He was acknowledged there as the eromenos of Heracles and had a tomb erected in his honor, where lovers went to pledge their faith to each other and to the hero, and the lover presented the beloved with a set of armor when the younger came of age.[2] This shrine still stood in the second century CE.[3] The two gymnasia in Thebes were dedicated one to Hercules and the other to Iolaus.[4] To honor the latter, the Thebans instituted a yearly athletic festival named the Iolaeia.[5]

History and practice

Theban pederasty was not the result of the "disaster of Laius," but it was the Theban lawgivers who instituted pederasty as an educational device for boys, in order to "soften, while they were young, their natural fierceness," and to "temper the manners and characters of the youth." [6] Xenophon states that "among the Boeotians, man and boy live together, like married people."[7] [8] Upon the boy's coming of age for military service, the lover presented him with all necessary weaponry.[9]

An early Theban lawgiver who was famed for his homoerotic attachment was Philolaus, a Corinthian who settled in Thebes and who also had as his beloved the Olympic athlete Diocles, another Corinthian. Their relationship was a lifelong one and may not have been pederastic.[10]

Towards the end of the Classical period of Theban history, Gorgidas, a renowned statesman and general formed a military battalion consisting of one hundred and fifty pairs of men with their youthful lovers, known as the Sacred Band of Thebes, which had the reputation of being unbeatable until they fell in battle against Philip II at Chaeronea in 338 BCE.

Contemporary (mostly Athenian) sources seem to indicate that pederasty in Thebes was freer than in other cities - indeed, unfettered - often referring to the Thebans as "Boeotian swine" for their rural ways.[11][12] In Plato's Symposium, the character Pausanias explains that the Theban rules encourage boys to satisfy their lovers sexually, so as to save the men the bother of convincing the youths - allegedly more difficult for Thebans on account of their poor speaking skills. The comic and philosophical contexts of Plato's work, however, must be taken into account when considering the historical veracity of this claim.[13] Modern comparative studies suggest that this picture of Theban pederasty is inaccurate, a result of nationalist and xenophobic attitudes on the part of the writers.[14]

Pindar, a Theban poet who is one of the few primary sources on Theban pederasty, presents a more conventional view, in which athletics and sexual desire are closely linked. Likewise, the ceramic paintings seem to depict a range of practices similar to those shown on vases from Athens and Corinth. [15]

Famous lovers

Epaminondas had two beloveds (eromenoi), according to Plutarch: Asopichus, who fought together with him at the battle of Leuctra, where he greatly distinguished himself;[16] and Caphisodorus, who fell with Epaminondas at Mantineia and was buried by his side. [17][18][19]

References

- ↑ William A. Percy, Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece, 1996; p.133

- ↑ Plutarch, Erotikos, 761d "And is it not a custom among you Thebans, Pemptides, for the lover to present the beloved with a complete suit of armor when he has come of age?"

- ↑ Pausanias, Guide to Greece, IX, 23.1

- ↑ Percy, 1996, p.134

- ↑ Pindar, Olympian Ode, VIII, 84

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Pelopidas

- ↑ Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaemonians II.12

- ↑ ibid, Symposium, 8.34

- ↑ Plutarch

- ↑ Aristotle, Politics, ii. 9

- ↑ Pindar, Olympian Ode VI

- ↑ Plutarch, Moralia, 995

- ↑ Plato, Symposium, 182 b1-b6

- ↑ Hupperts Charles, Boeotian Swine Homosexuality in Boeotia, Journal of Homosexuality, volume 49, pp.173–192, publisher Haworth Press

- ↑ "Boeotian Swine: Homosexuality in Boeotia," by Charles Hupperts, in Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West, ed. B. C. Verstraete and V. Provencal, Harrington Park Press, 2005, pp.180-190

- ↑ Atheneus, Deipnosophists, 605-606

- ↑ Plutarch, Dialogue on Love (Moralia 761)

- ↑ Stephen O. Murray, Homosexualities p.42

- ↑ "Yet it should be here noted that the military aspect of Greek love in the historic period was nowhere more distinguished than at Thebes. Epaminondas was a notable boy lover; and the names of his beloved Asopichus and Cephisodorus are mentioned by Plutarch." John Addington Symonds, A Problem in Greek Ethics; Ch. X; p. 35; University Press of the Pacific, Honolulu, 2002

See also

- Ancient Greece

- Harmodius and Aristogeiton

- Pederasty

- Pederasty in ancient Greece

- Philosophy of ancient Greek pederasty

- Symposium

Notes

- Greek Homosexuality, by Kenneth J. Dover; New York; Vintage Books, 1978, p.190ff. ISBN 0-394-74224-9

- Eros adolescent: La pédérastie dans la Grèce antique, by F. Buffière, Les Belles Lettres, Paris, 1980, pp.95-101 and 261-266

- Die Griechische Knabenliebe [Greek Pederasty], by Herald Patzer; Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1982. In: Sitzungsberichte der Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft an der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main, Vol. 19 No. 1.

- Homosexuality in Greek Myth, by Bernard Sergent; Beacon Press, 1986, pp.42-52. ISBN 0-8070-5700-2

- Percy, William A. Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece, Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996, pp.133-138. ISBN 0-252-02209-2

- Lovers' Legends: The Gay Greek Myths, by Andrew Calimach; Haiduk Press, 2001. ISBN 0-9714686-0-5

- Homosexuality in Greece and Rome, by Thomas K. Hubbard; U. of California Press, 2003. [1] ISBN 0-520-23430-8

- Lovers' Legends Unbound, by Andrew Calimach et al.; Haiduk Press, 2004. ISBN 0-9714686-1-3

- "Boeotian Swine: Homosexuality in Boeotia," by Charles Hupperts, in Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West, ed. B. C. Verstraete and V. Provencal, Harrington Park Press, 2005, pp.173-192