Catamite: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (8 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{History}} | |||

===Catamite=== | ===Catamite=== | ||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

==References in literature== | ==References in literature== | ||

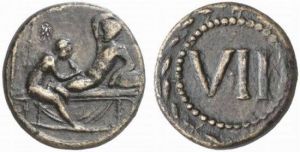

[[File:Roman coin celebrating pederasty.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Oral sex between a youth and an older male on a Roman coin or token probably used in a brothel.]] | |||

*In Plato's dialogue ''Gorgias'' (at 494d) Socrates uses the term in a conversation with Callicles contrasting appetites and contentment. | *In Plato's dialogue ''Gorgias'' (at 494d) Socrates uses the term in a conversation with Callicles contrasting appetites and contentment. | ||

*The word catamite appears widely but not necessarily frequently in the Latin literature of antiquity, from [[Plautus]] to [[Ausonius]]. It is sometimes a synonym for ''Puer delicatus'', "delicate boy". Cicero uses the term as an insult.<ref name="Cicero p. 95"/> The word became a general term for a boy raised for sexual purposes. | *The word catamite appears widely but not necessarily frequently in the Latin literature of antiquity, from [[Plautus]] to [[Ausonius]]. It is sometimes a synonym for ''Puer delicatus'', "delicate boy". Cicero uses the term as an insult.<ref name="Cicero p. 95"/> The word became a general term for a boy raised for sexual purposes. | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

*Anthony Burgess's 1980 novel ''Earthly Powers'' uses the word in its "outrageously provocative"<ref name="Tel">[http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/culture/jameshiggs/4739703/An_arresting_opening/ An arresting opening] </ref> opening sentence: "It was the afternoon of my eighty-first birthday, and I was in bed with my catamite when Ali announced that the archbishop had come to see me." | *Anthony Burgess's 1980 novel ''Earthly Powers'' uses the word in its "outrageously provocative"<ref name="Tel">[http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/culture/jameshiggs/4739703/An_arresting_opening/ An arresting opening] </ref> opening sentence: "It was the afternoon of my eighty-first birthday, and I was in bed with my catamite when Ali announced that the archbishop had come to see me." | ||

*In the postapocalyptic landscape of Cormac McCarthy's novel ''The Road'', the narrator describes an army on the move on foot with "women, perhaps a dozen in number, some of them pregnant, and lastly a supplementary consort of catamites." <ref>{{cite book|last=McCarthy|first=Cormac|title=The Road|year=2006|publisher=Vintage International|isbn=9780307387899|pages=92}}</ref> | *In the postapocalyptic landscape of Cormac McCarthy's novel ''The Road'', the narrator describes an army on the move on foot with "women, perhaps a dozen in number, some of them pregnant, and lastly a supplementary consort of catamites." <ref>{{cite book|last=McCarthy|first=Cormac|title=The Road|year=2006|publisher=Vintage International|isbn=9780307387899|pages=92}}</ref> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

==See also== | |||

*[[Young friend]] {{puce}} [[Loved boy]] {{puce}} [[Beloved]] | |||

* [[Eromenos]] | |||

* [[Paidika (dictionary)|Paidika]] | |||

* [[Sporus]] | |||

{{Navbox Ancient Rome|collapsed}} | |||

{{Navbox Pederasty|collapsed}} | |||

[[Category:Ancient Rome]] | [[Category:Ancient Rome]] | ||

Latest revision as of 02:28, 2 July 2022

| Part of the boylove history series |

|

| Portal:History |

Catamite

In its ancient usage, a catamite[1] (Latin catamitus) was a pubescent boy who was the intimate companion of a young man in ancient Rome, usually in a pederastic friendship.[2] It was usually a term of affection and literally means "Ganymede" in Latin. It was sometimes used as a term of insult.[3] The word derives from the proper noun Catamitus, the Latinized form of Ganymede, the beautiful Trojan youth abducted by Zeus to be his companion, lover, and cupbearer.[4] The Etruscan form of the name was Catmite, from an alternate Greek form of the name, Gadymedes.[5]

Puer delicatus

The puer delicatus[6] was an "exquisite" or "dainty" child-slave chosen by his master for his beauty as a sexual partner, referred to as puer (Latin for boy) and deliciae ("sweets" or "delights").[7] Unlike the freeborn Greek eromenos ("beloved"), who was protected by social custom, the Roman delicatus was a slave.[8] The boy was sometimes castrated in an effort to preserve his youthful qualities; the emperor Nero had a puer delicatus named Sporus, whom he castrated and married.[9]

Pueri delicati might be idealized in poetry. In the erotic elegies of Tibullus, the delicatus Marathus wears lavish and expensive clothing.[10] The beauty of the delicatus was measured by Apollonian standards, especially in regard to his long hair, which was supposed to be wavy, fair, and scented with perfume.[11] The mythological type of the delicatus was represented by Ganymede, the Trojan youth abducted by Jove (Greek Zeus).[12] In the Satyricon, the tastelessly wealthy freedman Trimalchio says that as a child-slave he had been a puer delicatus servicing both the master and the mistress of the household.[13]

References in literature

- In Plato's dialogue Gorgias (at 494d) Socrates uses the term in a conversation with Callicles contrasting appetites and contentment.

- The word catamite appears widely but not necessarily frequently in the Latin literature of antiquity, from Plautus to Ausonius. It is sometimes a synonym for Puer delicatus, "delicate boy". Cicero uses the term as an insult.[3] The word became a general term for a boy raised for sexual purposes.

- Stephen Dedalus ponders the word in Ulysses when discussing accusations that William Shakespeare might have been a pederast.

- C. S. Lewis in his partial autobiography Surprised by Joy described the social roles during his time at Wyvern College including the role of "Tart": "a pretty and effeminate-looking small boy who acts as a catamite to one or more of his seniors..." and noted that "pederasty...was not [frowned upon as seriously as] wearing one's coat unbuttoned." [14]

- Anthony Burgess's 1980 novel Earthly Powers uses the word in its "outrageously provocative"[15] opening sentence: "It was the afternoon of my eighty-first birthday, and I was in bed with my catamite when Ali announced that the archbishop had come to see me."

- In the postapocalyptic landscape of Cormac McCarthy's novel The Road, the narrator describes an army on the move on foot with "women, perhaps a dozen in number, some of them pregnant, and lastly a supplementary consort of catamites." [16]

References

- ↑ Article adapted from Wikipedia

- ↑ Craig Williams, Roman Homosexuality (Oxford University Press, 1999, 2010), pp. 52–55, 75.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cicero, frg. B29 of his orations and Philippics 2.77; Bertocchi and Maraldi, "Menaechmus quidam," p. 95.

- ↑ Alastair J.L. Blanshard, "Greek Love," in Sex: Vice and Love from Antiquity to Modernity (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), p. 131. Both Servius, note to Aeneid 1.128, and Festus state clearly that Catamitus was the Latin equivalent of Ganymedes; Festus says he was the concubinus of Jove. Alessandra Bertocchi and Mirka Maraldi, "Menaechmus quidam: Indefinites and Proper Nouns in Classical and Late Latin," in Latin vulgaire–Latin tardif. Actes du VIIème Colloque international sur le latin vulgaire et tardif. Séville, 2–6 septembre 2003 (University of Seville, 2006), p. 95, note 16.

- ↑ Larissa Bonfante and Judith Swaddling, Etruscan Myths (University of Texas Press, 2006), p. 73.

- ↑ Homosexuality in ancient Rome

- ↑ Guillermo Galán Vioque, Martial, Book VII: A Commentary (Brill, 2002), p. 120.

- ↑ Manwell, "Gender and Masculinity," p. 118.

- ↑ Caroline Vout, Power and Eroticism in Imperial Rome (Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 136 (for Sporus in Alexander Pope's poem "Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot", see Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel?).

- ↑ Alison Keith, "Sartorial Elegance and Poetic Finesse in the Sulpician Corpus," in Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture, p. 196.

- ↑ Fernando Navarro Antolín, Lygdamus. Corpus Tibullianum III.1–6: Lygdami Elegiarum Liber (Brill, 1996), pp. 304–307.

- ↑ Vioque, Martial, Book VII, p. 131.

- ↑ William Fitzgerald, Slavery and the Roman Literary Imagination (Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 54.

- ↑ Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life, Chapter IV Bloodery, pp.83-84, C.S.Lewis

- ↑ An arresting opening

- ↑ McCarthy, Cormac (2006). The Road. Vintage International. pp. 92. ISBN 9780307387899.