Philosophy of ancient Greek pederasty: Difference between revisions

Replaced the redirect code with the new content of the page |

|||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

*[[Pederasty in ancient Greece]] | *[[Pederasty in ancient Greece]] | ||

*[[The Philosophy of Responsible Boylove]] | *[[The Philosophy of Responsible Boylove]] | ||

==External links== | |||

*[https://greek-love.com/ Greek Love Through the Ages] | |||

{{Navbox Pederasty|collapsed}} | {{Navbox Pederasty|collapsed}} | ||

Revision as of 19:06, 5 September 2021

The topic of pederasty, one that took pride of place over the love of women in the erotic lives of Greek aristocrats in general and 5th century BC Athenians in particular[1], was the subject of extensive analysis in the Greek philosophical schools as well as in later writings of antiquity. Some of the principal dilemmas discussed were:

- What is the place of pederasty in a sacred view of the world?

- What kind of lover should a wise boy choose?

- Which form should pederasty take: erotic but chaste, or sexually expressed?

- Is pederasty right or wrong?

- Is pederasty better or worse than the love of women?

Philosophy itself was a discipline practiced in an intensely homosocial environment, and many - if not all - of its practitioners also engaged in homoerotic relationships, some of a pederastic nature, others not. For example, after the deaths of Plato and of his successor, the presidency of the Academy passed from lover to beloved for the next one hundred years.[2] Of the Stoics, Chrysippus, Cleanthes, and Zeno fell in love with boys.

| Part of the boylove history series |

|

| Portal:History |

Chaste pederasty

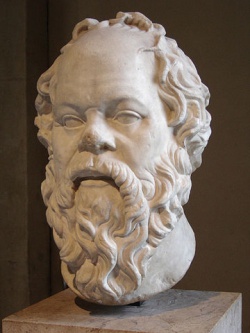

Plato was among the first to analyze and critique the traditions of male love current in their time, the fourth century BC. His works document the teachings of Socrates, who appears to have favored chaste pederastic relationships, marked by a balance between desire and self-control. He pointedly criticized purely physical infatuations, for example by mocking Critias' lust for Euthydemus by comparing his behavior towards the boy to that of a "a piglet scratching itself against a rock" (Xenophon, Memorabilia 1.2.29-30). That, however, did not prevent him from frequenting the boy brothels, from which he bought and freed his future friend and student, Phaedo,[3] nor from describing his erotic intoxication upon glimpsing the beautiful Charmides' naked body beneath his open tunic (Plato, Charmides 155c-e).

Socrates' love of Alcibiades, which was more than reciprocated, is held as an example of chaste pederasty. His desire for the boy is commented upon in several texts. In Plato's Gorgias,481d, Socrates asserts that he is "in love with two objects — Alcibiades, son of Clinias, and philosophy." In his Protagoras, 309a, Socrates is teased for his infatuation, "Where have you come from Socrates? No doubt from pursuit of the captivating Alcibiades. . . He's actually growing a beard." Socrates replies, "What of it? Aren't you an enthusiast for Homer, who says that the most charming age is that of the youth with his first beard, just the age of Alcibiades now?" But in the Symposium it comes out that despite his love for the youth, and despite the desperate advances of Alcibiades, who craves to have Socrates as a lover in every sense of the word, Socrates spends the night in bed with Alcibiades without satisfying his beloved's desires, and their mutual love remains chaste. (Cf. Aeschines Socraticus' dialogue the Alcibiades.)

This sexually restrained form of Greek pederasty has been called, since the Italian Renaissance, "Platonic love." According to T. K. Hubbard, "'Platonic love,' as articulated in Plato's Symposium and Phaedrus, attempts to rehabilitate pederastic desire by sublimating it into a higher, spiritual pursuit of Beauty in which the sexual appetite is ultimately transcended. The idea of a chaste pederasty gained currency in other fourth-century authors, and may have some precedent in Spartan customs."[4][5]

Phaedrus

In the dialogue Phaedrus Socrates described ideal pederasty as a relationship inspired by divine madness, a madness which "is given us by the gods to ensure our greatest good fortune." He describes a man’s falling in love with a beautiful boy as “the best and noblest of all the forms that possession by a god can take" [249] and the relationship as one in which the boy reminds the lover of the divine, and the lover in turn helps the boy attain divine qualities. This ideal relationship, while physically intimate and affectionate, is chaste in that it stops short of sexual intercourse. This kind of love Socrates labels philosophical pederasty. He states that those who practice love in this fashion, with modesty and full control, gain "bliss and shared understanding," and asserts that "there is no greater good than this that either human self-control or divine madness can offer a man." [256]

Sexually expressed pederasty is set one level below the philosophical. The quality of the friendship between the lovers is also strong, since they too are inspired by the same kind of divine madness, but its strength does not equal to that of the higher kind. On the lowest rung Socrates places pederastic relationships between individuals who are not truly in love with each other. These he regards as profane, rather than sacred, and their benefits, if any, remain on a mundane level. Both of these relationships are criticized as being shameful and damaging to the lover as well as the beloved, and are characterized as being fundamentally materialistic and predatory: "Do wolves love lambs? That’s how lovers befriend a boy." [241]

Laws

Later, in the Laws, Plato further elaborates on the concept of chaste pederasty (now in his own voice) by positing three types of love, or "philia," which can reach the level of “eros” when intense. First he presents those between equals and between unequals. The second is one marked by conflict between first two types, a conflict that resolves into chaste pederasty when physical desire is held in check by self-control. The third type of lover is said to “prefer to remain continually chaste with a beloved who is chaste.” This love, suggests Plato, is the one that an ideal law would favor, while simultaneously “keeping out the other two, if at all possible.”[837]

Other examples

Aristotle, while not specifically discussing constructions of pederasty, nevertheless suggests that it is obvious to him and his contemporaries that it is better to have a beloved who is disposed to grant his sexual favors but abstains, to having a beloved who is averse to granting his favors but nevertheless obliges. He thus concludes that in such relationships the goal is not so much the sexual act as the attainment of reciprocated affection. [Prior Analytics, 2.22]

Plutarch and Xenophon, in their descriptions of Spartan pederasty, state that even though it is the beautiful boys who are sought above all others (contrary to the Cretan traditions), nevertheless the pederastic couple remains chaste. In his Lacaedemonian Republic (II, 13), Plutarch goes so far as to assert that for an erastes to desire his eromenos would be as shameful as for a father to desire his own son. Nonetheless, the opinion on the Athenian street was at variance: The sexual character of Spartan pederasty was a running gag in the repertoire of Athenian comedians, and the verb λακωνίζω / lakônízô ("to do it the Lacedaemonian way") took on the meaning of "to sodomize."

- For more on the Platonic idealization of chaste pederasty see Michel Foucault's The Use of Pleasure, (Parts IV and V) and Platonic love.

Ethical critiques

The forms which pederasty took varied from one city to another, and were subject to comparison and evaluation. For example, the character of Pausanias in Plato's Symposium posits that the ideal construction of erotic relations between men and boys is the middle ground between the two extremes of, on one hand, foreign lands where such relations are forbidden altogether and, on the other hand, cities such as Elis and Boeotia, where men are unskilled in speech and boys are permitted to yield uncritically. That middle ground, claimed by Pausanias for Athens and Sparta, is one where men are well versed in the art of rhetoric and boys relate critically to their suitors, choosing only the most persuasive. Thus Plato draws a relationship between political systems, erotic expression, and intellectual sophistication as reflected in the art of speaking.[6]

Male relationships were represented in complex ways, some honorable and others dishonorable. But for the vast majority of ancient historians for a man to have not had a youth for a lover presented a deficiency in character. Plato was among those who spoke up against the decadence into which traditional Athenian pederasty was sinking. In his early works (the Symposium or in Phaedrus) he does not question the principles of pederasty, and states, referring to same-sex relationships:

- For I know not any greater blessing to a young man who is beginning in life than a virtuous lover, or to a lover than a beloved youth. For the principle, I say, neither kindred, nor honor, nor wealth, nor any motive is able to implant so well as love. Of what am I speaking? Of the sense of honor and dishonor, without which neither states nor individuals ever do any good or great work… And if there were only some way of contriving that a state or an army should be made up of lovers and their loves, they would be the very best governors of their own city, abstaining from all dishonor and emulating one another in honor; and it is scarcely an exaggeration to say that when fighting at each other’s side, although a mere handful, they would overcome the world.[7]

and again,

- [...] generally in countries which are subject to the barbarians, the custom is held to be dishonourable; loves of youths share the evil repute in which philosophy and naked sports are held, because they are inimical to tyranny; for the interests of rulers require that their subjects should be poor in spirit, and that there should be no strong bond of friendship or society among them, which love, above all other motives, is likely to inspire, as our Athenian tyrants learned by experience; for the love of Aristogeiton and the constancy of Harmodius had a strength which undid their power. [8]

Later, however, in his Laws, he blames them for promoting civil strife and driving many to their wits' end.[9] In particular Plato condemns sexual intercourse between males, asserting it to be unvirtuous in that it leads to cowardice in the one seduced and intemperance in the seducer.[10] As a remedy, Plato goes as far as to recommend the prohibition of pederasty, laying out a path whereby this may be accomplished. His strategy predicts closely the one that was eventually used by the various Christian sects to drive all same-sex relationships underground.[Citation needed]

Diogenes of Sinope is the subject of a number of anecdotes recorded by Diogenes Laertius, all of which depict him as strongly antagonistic to the sexual use of boys. One example: "To a youth who complained about the crowd of men who annoyed him, Diogenes said, "Stop displaying the signs of one who takes the passive role."[11]

Male versus female love

Other writers, often under the guise of debates between lovers of boys and lovers of women, have recorded other arguments used for and against pederasty. Some, like the charge that the practice was unnatural and not to be found among the lions and the bears, applied to all relationships between men and youths. According to Lucian (a late author, writing 700 years after the apogee of Classical pederasty), in his Erotes, "neither the birds who ride the winds, nor the fishes fated to their wet element, nor the animals on land seek dealing with other males." Lucian also expresses the concern that the reproduction of the species will suffer: "If everyone did like you there would be no one left!" They also mock philosophers' claims that it is the "soul" that they love. Again, Lucian: "How come your love, so full of wisdom, lunges avidly for the young, whose judgement is not yet fully formed, and who know not which road to take?"

Others' charges do not involve traditional pederasty, but practices devised for the sexual satisfaction of the strong at the expense of the weak. Chief among these is denouncement of the castration of captive slave boys. As Lucian has it, "Effrontery and tyrannical violence have gone as far as to mutilate nature with a sacrilegious steel, finding, by ripping from males their very manhood, a way to prolong their use.""Erotes" text at Diotima

Suppression of sexual pederasty

- From Laws

The Greek criticism of sexually expressed pederasty revolved around the two linked problems of the feminization of the boys and the lack of restraint of the men. Practitioners of such sexuality are also accused of "Intentionally killing the human race and sowing their seed on rocks and stones." In order to prevent these forms of masculine degradation, Plato suggested the use of the same psychological restraints which in his time prevented other forms of undesired sexual liaisons, such as incest. The method he suggests for "extinguishing the flames of pleasure" is to associate the sexual act between a man and a boy with 1. Uncleanliness, 2. Unholiness, and 3. Shamefulness. Plato asserts that the successful use of these techniques will lead to the “enslavement” of men’s desire for boys through a process of "frightening" and "bewitching" them into compliance. Such methods are effective, he claims, because no one ever contradicts them.

Notes

- ↑ "Plato considers love between people solely as a homosexual phenomenon, whereas his discussion of sex includes both heterosexual and homosexual relationships. The sociological setting of Platonism explains it: in 5th century Athens, apart from some outstanding exceptions, like Pericles’ legendary love for Aspasia, men were married for reproductive ends, yet reserved the term ‘love’ and the passionate activity of sexual love for homosexual relationships (Gonzalez-Reigosa, 1989; O’Connor, 1991; Tannahil, 1989)." [1]

- ↑ "The young Polemo came to Xenocrates' class to mock, was enchanted, shed a wife, and becoming the older man's lover, inherited his post. He in turn, loved Crates, who lived with him, succeeded him, and shared his tomb. The Platonic pair entertained another Academic couple at their table, Crantor and his eromenos, Arcesilaus. So for a full century, from 339 to 240, leadership in the Academy passed from lover to beloved." Plato, by Louis Crompton in glbtq.com Plato on glbtq.com

- ↑ Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers, 2.105

- ↑ Hubbard, Thomas K. "Introduction" to Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003. pg. 9.

- ↑ See also Kuefler, Mathew. The Manly Eunuch: Masculinity, Gender Ambiguity, and Christian Ideology in Late Antiquity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. pg. 200.

- ↑ "Pausanias specifically links the best type of pederastic love with the art of speaking. Pausanias stresses that in the backwoods (Elis and Boetia), where men are not clever at speaking (mê sophoi legein), the boys are expected to yield without being given arguments (logoi) to persuade (peithein) them; a situation he finds reprehensible. He points out that the despot, on the other hand, despises pederasty because he has no use for philosophy; nor, we may surmise, for persuasion either. It is only in Athenian (and Spartan?) society that arguments and persuasion are crucial to erotic relationships (or, more precisely, to erotic relationships between free males)." David Allan Gilbert, "Plato's Ideal Art of Rhetoric, an Interpretation of Phaedrus 270B-272B"; Unpublished doctoral dissertation, 2002; p187 [2]

- ↑ Plato, Phaedrus in the Symposium

- ↑ Plato, Symposium; 182c

- ↑ Plato, Laws, 636D & 835E

- ↑ Plato, Laws; 836c-d

- ↑ Diogenes Laertius, 6.47

See also

External links