Eromenos: Difference between revisions

Modified the introduction of the article |

|||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

==Characteristics of the role== | ==Characteristics of the role== | ||

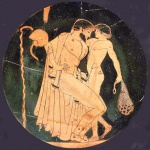

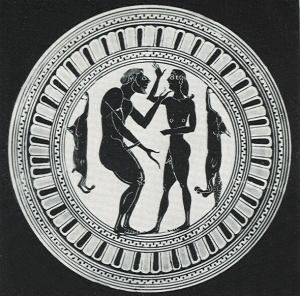

[[File:Erastes and Eromenos Flanked by a Dead Hare and a Dead Fox.png|thumb|right|Erastes and Eromenos Flanked by a Dead Hare and a Dead Fox. Attic black-figure cup by the Sokles Painter, c. 550–530 B.C. Swiss private collection.]] | [[File:Erastes and Eromenos Flanked by a Dead Hare and a Dead Fox.png|thumb|right|Erastes and Eromenos Flanked by a Dead Hare and a Dead Fox. Attic black-figure cup by the Sokles Painter, c. 550–530 B.C. Swiss private collection.]] | ||

The youth was expected to put up resistance to the entreaties of the various ''erastai'' seeking to win his affection, in order to test their seriousness of purpose, and to choose the most deserving. As a result, in Attica, ''eromenoi'' were assiduously courted, and were at times the object of street fights and arguments among the young men vying for their affection.<ref>Aeschines, ''Against Timarchos''.</ref> Some of the ''eromenoi'' moved in with their lovers, with whom they lived for some period of time, usually until coming of age. Most ''erastai''-''eromenoi'' relationships were expected to break apart | The youth was expected to put up resistance to the entreaties of the various ''erastai'' seeking to win his affection, in order to test their seriousness of purpose, and to choose the most deserving. As a result, in Attica, ''eromenoi'' were assiduously courted, and were at times the object of street fights and arguments among the young men vying for their affection.<ref>Aeschines, ''Against Timarchos''.</ref> Some of the ''eromenoi'' moved in with their lovers, with whom they lived for some period of time, usually until coming of age. Most ''erastai''-''eromenoi'' relationships were expected to break apart when the young partner entered adulthood (signaled by the growth of a beard), although a minority of couples stayed together as full-time lovers. | ||

The Greeks recognized and valued that time in the life of a boy when he was considered to be ripe for loving; the Greek word used to describe such a boy was ''hôraios'', meaning "in season" or "in bloom".<ref>Xenophon, ''Memorabilia'', 1.3.8–14.</ref> ''Eromenoi'' were generally males aged twelve to seventeen.<ref>Amy Richlin, "sexuality", in ''[[Oxford Classical Dictionary|Oxford Classical Dictionary]]'', 3rd ed., 1996, p. 1399.</ref> Though the ''eromenos'' was valued for his beauty, he was appreciated even more for his modesty, industriousness and courage. In [[Plato]]'s ''[[Symposium (Plato)|Symposium]]'' (191e–192a), the character Aristophanes says that the ''eromenoi'' who "love men and enjoy lying with men and being embraced by men" are not shameless, but rather "the best of boys and lads, because they are the most manly in their nature" (though this may have been a view held by aristocratic Athenians of Plato and Aristophanes' type, the nature of Platonic dialogues makes it uncertain whether it was actually held by either Plato or Aristophanes themselves). | The Greeks recognized and valued that time in the life of a boy when he was considered to be ripe for loving; the Greek word used to describe such a boy was ''hôraios'', meaning "in season" or "in bloom".<ref>Xenophon, ''Memorabilia'', 1.3.8–14.</ref> ''Eromenoi'' were generally males aged twelve to seventeen.<ref>Amy Richlin, "sexuality", in ''[[Oxford Classical Dictionary|Oxford Classical Dictionary]]'', 3rd ed., 1996, p. 1399.</ref> Though the ''eromenos'' was valued for his beauty, he was appreciated even more for his modesty, industriousness and courage. In [[Plato]]'s ''[[Symposium (Plato)|Symposium]]'' (191e–192a), the character Aristophanes says that the ''eromenoi'' who "love men and enjoy lying with men and being embraced by men" are not shameless, but rather "the best of boys and lads, because they are the most manly in their nature" (though this may have been a view held by aristocratic Athenians of Plato and Aristophanes' type, the nature of Platonic dialogues makes it uncertain whether it was actually held by either Plato or Aristophanes themselves). | ||

Revision as of 21:38, 11 April 2019

| Part of the boylove history series |

|

| Portal:History |

In the pederastic tradition of Classical Athens, the eromenos ("beloved"; Greek: ἐρώμενος, pl. ἐρώμενοι, eromenoi) was an adolescent boy who was involved in an educational homoerotic relationship with an adult man, known as the erastes ("lover"; Greek: ἐραστής, pl. ἐρασταί, erastai).

The term for the role often varied from one polis to another. In Athens, the eromenos was also known as paidika; in Sparta they used aites (hearer), a term also used in Thessaly;[1] in Crete the boys were known as kleinos (glorious) and, if they had fought in battle with their lover, as parastathenes (one who stands beside).

The ideal eromenos—as well as his erastes—was expected to be ruled by the principles of enkrateia, or "self-mastery", which presumed an attitude of moderation and self-restraint in all matters.

Characteristics of the role

The youth was expected to put up resistance to the entreaties of the various erastai seeking to win his affection, in order to test their seriousness of purpose, and to choose the most deserving. As a result, in Attica, eromenoi were assiduously courted, and were at times the object of street fights and arguments among the young men vying for their affection.[2] Some of the eromenoi moved in with their lovers, with whom they lived for some period of time, usually until coming of age. Most erastai-eromenoi relationships were expected to break apart when the young partner entered adulthood (signaled by the growth of a beard), although a minority of couples stayed together as full-time lovers.

The Greeks recognized and valued that time in the life of a boy when he was considered to be ripe for loving; the Greek word used to describe such a boy was hôraios, meaning "in season" or "in bloom".[3] Eromenoi were generally males aged twelve to seventeen.[4] Though the eromenos was valued for his beauty, he was appreciated even more for his modesty, industriousness and courage. In Plato's Symposium (191e–192a), the character Aristophanes says that the eromenoi who "love men and enjoy lying with men and being embraced by men" are not shameless, but rather "the best of boys and lads, because they are the most manly in their nature" (though this may have been a view held by aristocratic Athenians of Plato and Aristophanes' type, the nature of Platonic dialogues makes it uncertain whether it was actually held by either Plato or Aristophanes themselves).

The eromenos was typically portrayed as undergoing pedagogical training, and while he typically was also the object of affection and passion, he was not necessarily sexually engaged. When present, sexual expression is depicted in the iconography as having consisted primarily of fondling and intercrural sex. Anal sex appears to have been less common, yet frequent enough to be a topic of comedy, and of criticism based on the opinion that it was a was a shameful practice[5] and risked feminizing the boys who grew to like it.

Upon reaching the age of maturity (around eighteen years), the eromenos would cut his long hair and become eligible for taking on the role of erastes, and courting and winning an eromenos of his own.

Eromenos is traditionally translated into English as "beloved", although this is not a perfect match for the concept.