Erastes: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

*[[Pederasty in ancient Greece]] | *[[Pederasty in ancient Greece]] | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

*[http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0090-5917%28199405%2922%3A2%3C253%3ACAEEIA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-5&size=LARGE&origin=JSTOR-enlargePage Sara Monoson, "Citizen as Erastes: Erotic Imagery and the Idea of Reciprocity in the Periclean Funeral Oration"] | *[http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0090-5917%28199405%2922%3A2%3C253%3ACAEEIA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-5&size=LARGE&origin=JSTOR-enlargePage Sara Monoson, "Citizen as Erastes: Erotic Imagery and the Idea of Reciprocity in the Periclean Funeral Oration"] | ||

{{Navbox Pederasty|collapsed}} | |||

{{Navbox Ancient Greece}} | {{Navbox Ancient Greece}} | ||

Latest revision as of 22:35, 2 July 2022

In ancient Greece, the erastes ("lover"; Greek: ἐραστής, pl. ἐρασταί, erastai) was an adult male involved in a pederastic relationship with an adolescent boy called the eromenos ("beloved"; Greek: ἐρώμενος, pl. ἐρώμενοι, eromenoi). Erastes was in particular an Athenian term for this role. Other terms were, in Sparta, eispnelas, "inspirer", and in Crete, philetor, "befriender".

The word was also used as a general term for any male admirer courting a particular boy, even if he had not been accepted by the boy as a bona fide lover.

Characteristics of the role

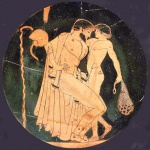

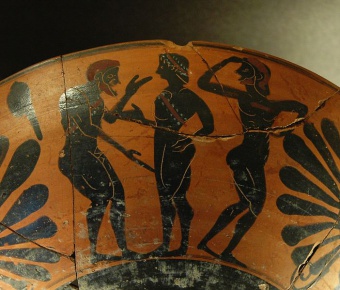

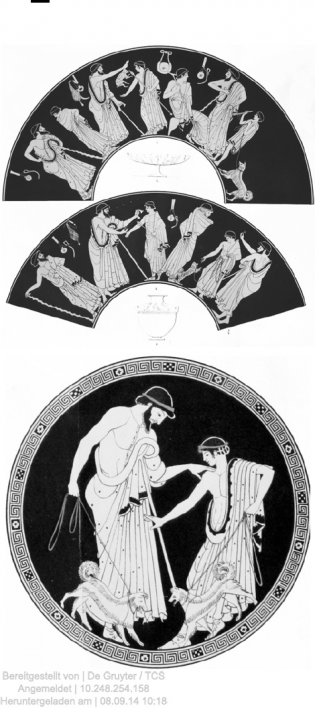

Iconographic representations of pederastic couples usually—but not always—depict the erastes as bearded, while the eromenos is always beardless. However, the erastes was typically not yet of marriageable age, roughly between twenty and thirty years old. Wide differences in age were considered an obstacle to such relationships, as evidenced by Aristotle's assertion that Solon could not have been the erastes of Pisistratus as the difference in age between the two was too great (around 31 years).[1]

When the relationship had a sexual aspect, the erastes was the active partner, and the love-making is usually depicted as frontal, standing up, and between the thighs. In mythology, the erastes was exemplified by deities such as Zeus and Apollo, and heroes such as Hercules and Orpheus.

A number of ancient sources, such as Plato's Phaedrus and Aeschines' Against Timarchos, indicate that the ideal erastes was restrained in his relations with his beloved, and his love was an expression of his generosity and sympathy. He is contrasted to the man who hires boys for his pleasure and "behaves grossly" with them, the mark of an abusive and uneducated person.[2] Xenophon also comments, incidentally, on one of the characteristics of the ideal erastes, indicating that such a man would hide nothing concerning the eromenos from the father of that youth.[3]

In some states he was the one who initiated the love affair by courting or ritually kidnapping the boy, while in others, such as Sparta, it was the youth who requested the relationship. While the practice of pedagogic pederasty was encouraged and valorized, it seems to have been optional for the adult in all cities save Sparta, where it was mandated by law.

| Part of the boylove history series |

|

| Portal:History |

Erastai are often described as exerting a great deal of effort to attract the attention and the sympathy of an eromenos. This task often led to street fights with other suitors, family arguments, outrageous behavior like sleeping on the boy's stoop, writing of love poems, bestowing of gifts, and, at times, outright coercion.

Among the typical gifts given by an erastes to an eromenos are pets such as birds. Of these Aristophanes asserts: "Lovers give noble birds to their beloveds".[4]

Responsibilities

The function of the erastes was to love and educate—or provide for the education of—the youth. The nature of that education varied with the culture of their respective polis, but generally was grounded in the physical culture of the gymnasium, which included athletics and military training, as well as philosophical and musical studies. Erastai would on many occasions make a contract or promise with his intended or intendeds parents, setting the limits and terms of the relationship.

Another responsibility often consisted in managing the financial affairs of the youth, especially if he was fatherless; the erastes would have control of the estate until the youth came of age. At times this led to abuses and accusations of mismanagement and outright theft, as in the case of Demosthenes and his eromenos Aristarchus.[5] The erastes was generally an influential citizen, involved in the social and political life of his polis, often married and a pater familias, and enjoying a certain financial ease.

Taking on the responsibilities of a pederastic relationship was not inexpensive, in particular at the time of the festivities which were mandated by tradition. In Crete this entailed a banquet and a number of ritual gifts: an ox, to sacrifice to Zeus; a military outfit, signifying the attainment of warrior status by the eromenos; and a chalice symbolizing the youth's empowerment to attend symposia—as well as possible religious and ritual roles. It was not uncommon for friends of the erastes to contribute to the expenses, the celebration uniting the friends of both partners, much like a modern major family event.

While the ideal pederastic bond was constructed as an act of generosity by the lover towards the beloved, the lover's cultivation of arete (excellence) seems to have benefited himself as well as his young charge. According to Xenophon, it is self-evident that "any man, within the sight of his eromenos, excels himself and avoids doing or saying things which are base or cowardly so that he may not be seen by him".[6]

Political metaphor

The figure of the erastes as benefactor of his eromenos was entrenched in the minds of the Athenians to such an extent that political leaders made use of the role of the ideal erastes vis-a-vis his eromenos to symbolize the ideal relationship between a citizen and the polis. That figure of speech occurs in two separate instances.

Pericles, a man who seems to have abstained from relationships with boys and loved women deeply, used the model of the erastes as an example for Athenians to follow in their relationship with their own city. In a funeral speech ascribed to him by Thucydides he exhorts the Athenians to "gaze day after day on the power of the city and become her erastai", interpreted to mean that "citizen-soldiers" should behave towards Athens like boyfriends, erastai: i.e. love the city without calculation, more than life itself.[7]

In another instance, presented as a parody of the first and explored as such by Aristophanes in The Knights, the politician Cleon also styles himself as erastes to the demos. The reversal, in which only the orator casts himself in the role of erastes, is played for its full comic potential when, later in the play, the character Demos, representing the people, is chided for being overeager for Cleo's love, and for being naive as the lover, "in return, cheated and left".[8][9]

Notes

- ↑ "It is evident from this that the story is mere gossip which states that Pisistratus was the youthful favourite of Solon and commanded in the war against Megara for the recovery of Salamis. It will not harmonize with their respective ages, as any one may see who will reckon up the years of the life of each of them, and the dates at which they died." Aristotle, The Athenian Constitution, tr. Sir Frederic G. Kenyon.

- ↑ Aeschines, Against Timarchos, tr. Nick Fisher (2001) p. 103.

- ↑ Xenophon, Symposium, VIII.11.

- ↑ Suda, a643 [1].

- ↑ Aeschines, op.cit.

- ↑ Xenophon, Cynegeticus, 12:20.

- ↑ James Davidson, "Mr and Mr and Mrs and Mrs" in London Review of Books, June 2, 2005 [2], accessed Oct 1, 2007.

- ↑ Aristophanes, The Knights, 1340–44.

- ↑ Sara Monoson, Plato's Democratic Entanglements: Athenian Politics and the Practice of Philosophy, p. 87.

See also