Pederasty in the Middle East and Central Asia

- For a generalized discussion of relations between men and boys see main article: Pederasty

The practice of pederasty in the Middle East and Central Asia seems to have begun, according to surviving records, sometime during the 8th century, and ended, at least as an open practice, in the mid-19th century. Throughout this era, pederastic relationships, poetry, art, and spirituality were found in cultures from Moorish Spain (al-Andalus) to present-day Afghanistan, where it survives in the well-documented practice of bacha bazi. While sodomy (anal intercourse) was considered a major sin in Islam, particularly receptive sodomy, at times there was not even the pretense of enforcing this prohibition. Other aspects of same-sex relations were not considered sinful, though they were problematized or honored to various degrees at different times and places.

The seeming parallel growth of pederasty and Islam has been commented on by modern historians, who see a link between the love of boys and the protective attitude of Islam towards women, leading to their removal from public life, together with the tendency of Sharia law to accommodate within the domain of "private behavior" activities—for example, the use of drugs—that do not interfere with public order.[1]

Literature and teachings

| Part of the boylove history series |

|

| Portal:History |

Literature reflects Muslim culture's fascination with love (sexual and nonsexual), a love which includes beautiful boys. To many, if not most Muslim literary figures, love was love: as Urdu poet Hasrat Mohani put it, "All love is unconditionally good".[2] The lover was conceived as martyr and hero. His desire, known as ishq, was glorified as mad, unresonable, ecstatic, impossible to satisfy, and leading even to death. An Arab proverb claims that "Ishq is a fire that burns down everything but the object of desire".[3]

While pederastic themes abound in prose as well, it is through poetry that the genre has made its mark on the culture. This topos is found from Moorish Spain, such as in The Dove's Neck Ring of Ibn Hazm, to Egypt, in Shams al-Din Muhammad ibn Hasan al-Nawaji's Meadow of Gazelles (in Arabic poetry beautiful boys are frequently called gazelles), to Baghdad, in the person of Abu Nuwas, "enfant terrible" and first among Arab poets, to the Gulistan of the Persian Sa'adi, and Urdu poets such as Mir Taqi Mir and Mirza Ghalib in northern India.

Individual regions

Middle East

The construction of same-sex love in the Middle East has been influenced by its history and geography. Hellenistic elements can be recognized in the use of the boy cupbearer as a symbol of homoerotic passion. Another parallel is the belief that pederasty is absent from "primitive" cultures, since there a boy can learn all he needs from his father, but that people of high civilization require the erotic attraction of boys to motivate experienced men to teach the boys lovingly.[2]

The valorization of youthful male beauty is found in the Qurʾān itself: "And there shall wait on them [the god fearing men] youths of their own, as fair as virgin pearls". (Qurʾān 52:24; 56:17; 76:19). Islamic jurisprudence generally considers that attraction towards beautiful youths is normal and natural. The Hanbalite jurist Ibn al-Jawzi (d. 1200) is reputed to have said that "he who claims that he experiences no desire when looking at beautiful boys or youths is a liar, and if we could believe him he would be an animal, and not a human being".[3] However, anal intercourse (liwāṭ) is proscribed, and men are advised to be even more wary of attraction to beautiful boys than to beautiful women, through religious injunctions exhorting them to resist this temptation. It is related that the Prophet Muhammad enjoined his followers to "beware of beardless youths, for they are a greater source of mischief than young maidens".[4]

Likewise, the imam and legal scholar Sufyan al-Thawri (d. 783 CE) asserted, regarding sexual temptation, that "if every woman has one devil accompanying her, then a handsome lad has seventeen".[5]

Love of beauty, another quality praised in the hadith which records Muhammad as having said that "God is beautiful and loves beauty", and that a handsome face refreshes the eye, was seen as a mark of refined and sophisticated character, even in the appreciation of beautiful boys. The 17th-century Persian philosopher Sadr al-Din al-Shirazi asserted that:

We do not find anyone of those who have a refined heart and a delicate character. . . to be void of this love at one time or another in their life, but we find all coarse souls, harsh hearts and dry characters. . . devoid of this type of love, most of them restricting themselves to the love of men for women and the love of women for men with the aim of mating and cohabitation, as is in the nature of all animals.[6]

Persia

Some sources have posited that same-sex relations may have been introduced by the hordes of the early Soghdian (Central Asian Iranian) conqueror Afrasiab. The local population is said to have been greatly shocked by the popularity among his people for "the vice against nature". The Zoroastrian priests reacted strongly, and decreed that any man caught in the act could be put to death—a stronger sanction than that against murderers (Edward Westermarck, The Origin and Development of the Moral Ideas; London 1908, 1912, 1971).

The origin of pederasty in ancient Persia was debated even in ancient times. Herodotus claimed they had learned it from the Greeks: "... and [the Persians'] luxurious practices are of all kinds, and all borrowed: the Greeks taught them pederasty".[7] However, Plutarch asserts that the Persians used eunuch boys "the Greek way" long before they had seen the Grecian main.[8] Despite these historians, Richard Francis Burton was of the opinion that the Persians had picked up the habit from the people inhabiting the Tigris-Euphrates Valley.[9]

The practice was not without its critics, such as Sanai of Ghazni. The poet mocks the pederastic practices of his time, embodied in the doings of the Khvaja of Herat, who takes his catamite into the mosque for a quick tryst:

- Not finding shelter he became perturbed,

- The mosque, he reasoned, would be undisturbed.

But he is discovered by a devout man, who, in his blame, echoes a traditional attack on same-sex relations:

- "These sinful ways of yours,"—that was his shout—

- Have ruined all the crops and caused the drought![10]

Sanai drives the irony home by having the devout man, after the Khvaja makes his embarrassed escape, mount the boy and complete the act.

Dick Davis comments, "A further cultural barrier, and one that can prove particularly difficult to negotiate, is the prevalence of the cult of pederasty in much medieval Persian verse". He notes that many translators have taken advantage of the fact that pronouns are not gender specific but notes that the translator "in availing himself of this help he is, as he knows, often fudging the issue, quietly bowdlerizing the texts".[11] This is held to be true even of major works, such as the Gulistan (Rose Garden) of Sa'adi. English translators even in the tamer episodes of the Gulistan turn boys into girls and change anecdotes about pederasty into tales of heterosexual love.[12]

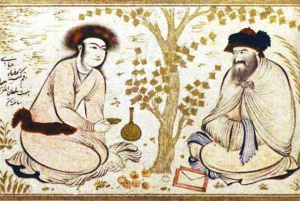

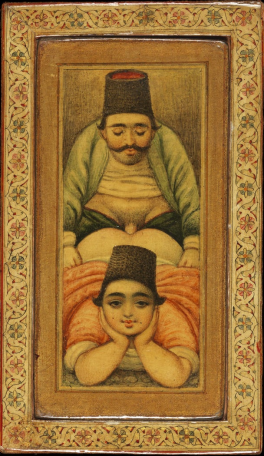

The visual arts also were inspired by the male love tradition. Though there are a few examples which are sexually suggestive, most of the time the works reflect the Sufi sensibilites which locate the attraction in the gaze. Thus very often we see depictions of male couples, a mature man in the company of a comely youth who is the object of his attention. Many of the artistic works of Reza Abbasi, whose patron was the Safavid monarch Shah Abbas, depict such handsome youths, often in the role of saqi, or "wine pourer", either alone or in the company of a man.

Thomas Herbert, the 21-year-old secretary to the English ambassador to Persia, later reported that at Abbas' court (some time between 1627 and 1629) he saw, "Ganymede boys in vests of gold, rich bespangled turbans, and choice sandals, their curled hair dangling about their shoulders, with rolling eyes and vermilion cheeks". This was also a time when male houses of prostitution amrad khaneh, "houses of the beardless", were legally recognized and paid taxes. Regarding this trade, John Chardin, traveling through Persia at the time, reported that he had found "numerous houses of male prostitution, but none offering females".

John Fryer, who traveled to Persia in the late seventeenth century, was of the opinion that "the Persians, when they let go their modesty... covet boys as much as women". The notoriety of the Persians for boyish pleasures was such that in the late nineteenth century Richard Francis Burton referred to Central Asian pederasty as "the Persian vice". He confirmed the findings of John Chardin, indicating that the boy bordellos continued to exist, adding that "the boys are prepared with extreme care by diet, baths, depilation, unguents and a host of artists in cosmetics". He accounted for the tastes of the Persians by postulating that the habit began in boyhood, when Persian boys used each other for sexual pleasure, in a game known as alish-takish. Later in life, after marrying and begetting children, the "paterfamilias returns to the Ganymede", according to Burton.[13]

Ottoman Empire

The early modern Ottoman Empire, despite being an Islamic empire, produced many primary sources which indicate the existence of male-male love among its citizens. At present, many historians are still having disagreements with regard to male-male relationships in early modern Ottoman society—some argue on the gender of the beloveds being portrayed in poems,[14] some disagree on the tolerance for sodomy.[15] These variations in opinions and the sometimes seemingly contradicting primary sources—literary work describing male-male relationships and yet laws prohibiting sodomy—create a constantly evolving field of study.

Sodomy and Islam

Perhaps one of the most abstruse aspects of male-male relationship in the Ottoman Empire is its coexistence with the Islamic law, which according to a number of historians today, condemns "homosexuality".

Historian Marshall Hodgson wrote that in medieval Islamic civilization,

Despite strong Shar‘i disapproval, the sexual relations of a mature man with a subordinate youth were so readily accepted in upper-class circles... The fashion entered poetry, especially the Persian.

Bernard Lewis also wrote that,

Homosexuality is condemned and forbidden by the holy law of Islam, but there are times and places in Islamic history when the ban on homosexual love seems no stronger than the ban on adultery.[16]

Khaled El-Rouayheb suggested that what Islamic law prohibits is sexual intercourse between men (sodomy), and that Islamic religious scholars of that period clearly did not believe that falling in love with a boy or expressing love in poetry was also illicit.[16] Perhaps by taking a look at Deli Birader's The Repeller of Grief and Remover of Anxiety, El-Rouayheb's claim can be better understood. The following is an excerpt from the third chapter of Birader's work:

He confronts a silver ass

And attains all he desires

All at once, he raises his gown

And take the silver dome in front

Then he makes his cock as hard as a rock

And plunges it up to the black hair at its base,

These are then names contemptible lovers, and the leader of sinners, lûtî, gulâmpâre,[17] ‘white money black face.’

Their beloved may prevent them from verifying his to the point and contend themselves with being next to him, now sucking his lips, now embracing him, and their foolish hearts are deluded by him: He gets a playful beloved

He follows the path of loyalty in love

His limit should be fooling around

He should never cross this limit

He should pull him aside, into his embrace

And delude his foolish heart with that much

These are then named as loyal lovers, and favorable sweethearts, mahbub-perest, a double side drum...[18]

The existence of pederastic love

Even if it is granted that literary works during the Ottoman period can be used as valid primary sources that reflect on the lifestyle of the habitants of the Ottoman Empire, Khaled El-Rouayheb expressed in another piece of his work, The Love of Boys in Arabic Poetry of the Early Ottoman Period, 1500–1800, that many historians "give readers the impression that many love poetry of that period usually portrayed female beloved". In the aforementioned paper, El-Rouayheb later argued that "the portrayed beloved was often, perhaps most often, a male youth". In summary, he based his arguments on the physical description, namely the beard, of the beloved, the name of the beloved, the usage of masculine gender terms when speaking of the beloved, and extra-poetic information attached to the poems.[19]

The following are excerpts from poems used for each of El-Rouayheb's claim:

i. beard-down (‘idhār)—Ahmad al-Bahnasī (d. 1148/1735): There he is with the night of the face’s ‘idhār when it darkened.

ii. beloved’s name—Ibrāhīm al-Akramī (d. 1047/1638): After you, my desire ‘Ali, I’ve divorced of the vine and love poetry.

iii. the word “boy”—Muhammad al-Mahāsinī (d. 1062/1662): I fancy him, a lithesome boy of paradise.

Women-lovers and boy-lovers

The existence of literary works with both women-lovers and boy-lovers would substantiate the prevalence of both the "categories" of lovers. An example of such a work would be Deli Birader's The Repeller of Grief and Remover of Anxiety—"a lengthy work in prose with several poems embedded in it".[20] There are seven chapters in Birader's work. Chapter 2 was titled "Boy-lovers and women-lovers", Chapter 3 was titled "How to enjoy the company of boys", and Chapter 4 was titled "How to enjoy the company of girls".

Age discrimination: Beardless boys and downy-cheeked youths

In many of the poems with boy-beloveds, there seems to be a distinction in age, namely, between beardless boys and downy-cheeked youths, where authors often expressed preference for one over the other.

Syrian scholar Muhammad Khalīl al-Murādī "devoted 12 pages of his biographical work to reproducing a tract... entitled 'Throwing off the reins in describing the devoid of, and the embellished with, beard-down'... [which depicts] a disputation in which the beardless boy and the downy-cheeked youth advance their respective boasts as to who was the most appropriate object of passionate love".[21]

The following excerpts of poems also exemplify the correlation between age and beauty in the minds of the authors:

‘Abd al-Hayy al-Khāl (d. 1117/1705): I used to say that my heart would forget [you] when ‘ārid[22] appeared on your cheeks.

Mustafā al-Sumādī (d. 1137/1725): If beard-down appears on the cheeks of the beloved, it will leave him dusted and dried.

In Chapter 3 of Deli Birader's The Repeller of Grief and Remover of Anxiety, titled "How to enjoy the company of boys", Birader described a few group of lovers—those that find beauty in exquisite boys, those who love güzeshte (boys who have passed puberty), those who think of "beauties who have already grown black and thick moustaches" and others who strive to find old men with white beards.[23] These examples imply how contemporary authors' preference for male subjects was defined by the age of the subjects.

Bathhouses and coffeehouses

Traditionally, the masseurs in the baths, tellak in Turkish, who were young men, helped wash clients by soaping and scrubbing their bodies. They also doubled as sex workers.[24] We know today, by texts left by Ottoman authors, who they were, their prices, how many times they could bring their customers to orgasm, and the details of their sexual practices (from the Dellâkname-i Dilküşâ, 18th-century work by Dervish, Ismail Agha; Ottoman archives, Süleymaniye, Istanbul).[25][26]

They were recruited from among the ranks of the non-Muslim subject nations of the Turkish empire, such as Greeks, Armenians, Jews, Albanians, Bulgarians, Roma and others.

Primary sources indicate the hiring of handsome boys as workers in bathhouses (hammam) and coffeehouses. Cam Hobhouse, in his travels, came across the following verses, written on the window of a hammam, probably describing a tellak:

Dear youth, whose form and face unite

To lead my sinful soul astray;

Whose wanton willing looks invite

To every bliss, and teach the way,

Ah spare thyself, thyself and me,

Withhold the too-distracting joy;

Ah cease so fair and fond to be,

And look less lovely, or more coy.[27]

Also, the following is an excerpt of a poem praising the beauty of a coffeehouse waiter (sāqī) called Ibrāhīm al-Suyūrī, in the Dīwān of ‘Ināyātī:

Come, let us polish our rusty souls with the Ibrahimic visage.

Come, let us gaze at the luminous moon which puts the bright sun to shame.

Come, let us look at the tender branch, swaying in radiant garments.

Come, let us take the cup from the lavish hand...[28]

The Damascene scholar Muhammad Najm al-Dīn al-Ghazzī once commented:

Consensus has now been reached that it [coffee] is permissible in itself. As for passing it around like an alcoholic beverage, and playing musical instruments in association with it, and taking it from handsome beardless boys while looking at them and pinching their behinds, there is no doubt as to its prohibition.[29]

An Egpytian scholar, ‘Abd al-Ra’ūf al-Munāwī, urged the owner of a bath not to employ handsome boys to avoid being classed with pimps and procurers on Judgment Day. Khaled El-Rouayheb also wrote that "in some instances, legal action was taken against the more disreputable establishments on the basis of their association with immorality and prostitution".[28]

Perception of Christendom

The sexual doings of the Turks came under frequent criticism by their Christian neighbors. The Chronicles of the Moldavian Land mention that the Ottomans, upon the sack of Crimea in 1475, sailed away with a galleon filled with one hundred and fifty young boys destined for "the filthy sodomy of the whoring Turk". Thomas Sherley, held captive by the Ottomans between 1603 and 1605 under harsh circumstances, reported in his Discourse of the Turks that "for their Sodommerye they use it soe publiquely and impudentlye as an honest Christian woulde shame to companye his wyffe as they do with their buggeringe boys". John Cam Hobhouse, an early traveller to Istanbul with his friend Lord Byron, described the köçek dances as "beastly". The anonymous poem Don Leon (written in the voice of Byron and ascribed to him by some) refers to Turkish boy prostitution as a "monstrous scene". Osman Agha of Temeşvar, who fell captive to the Austrians in 1688, wrote in his memoirs that one night an Austrian boy approached him for sex, telling him "for I know all Turks are pederasts".[30]

Algiers

Ottoman Algiers was mostly self-governing, although there was an Ottoman governor. Closer to western Europe, but isolated, it served as a gay ghetto of sorts, filled with Europeans from every country, some fleeing from the law or family responsibilities, who converted to Islam, adopted Islamic names, and proceeded to run the city, occupying all the positions of authority below the governor. Boylove was, at worst, a pecadillo, and there was no need for secrecy (in Europe at the time, people would be hung for homosexual sex of any sort). A sixteenth-century Spanish historian of Algiers, Diego de Haedo, tells us with outrage that sex even took place in the streets, and others would gather around to watch and cheer.

The city's industry was piracy, and a key part of this piracy was selling into slavery, including sexual slavery, young and pretty boys and girls (the "fate worse than death"). Christian passengers and crew members of ships sailing the Mediterranean, prominent and wealthy travelers, usually older males who were worth less as slaves, were held for ransom. Another source of slaves was people captured during raids on the north coast of the Mediterranean, part of which became almost uninhabited during the Ottoman pre-colonialization period (sixteenth through eighteenth centuries). The very first mission of the newly-constituted United States Navy, in 1801, was to sail to Algiers to end piracy, at least as it affected Americans and American ships.[31][32] Suppression of piracy was a key reason for the French colonialization of North Africa in the early nineteenth century.

Central Asia

In Central Asia, the practice of pederasty is reputed to have long been widespread. The paragon of the practice can be said to have been the love between Sultan Mahmood of Ghazni and his slave, Ayaz. The Sultan is seen as an example of the man who, because of the power of his love, becomes "a slave to his slave". Ayaz came to be recognized as the ideal beloved, and a model of purity in Sufi literature. The two have gained pride of place among the favorite pairs of lovers in Persian literature. Modern scholars, such as Prods Oktor Skjœrvø, the Aga Khan Professor of Iranian Studies at Harvard University, consider the relationship between the two to have been one example of the pederasty practiced at the Turkish Courts: "Under the Turkish Ghaznavid, Seljuq, and Khawarazmshah rulers of Iran in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, pederasty was quite common in courtly circles".[33]

In the "Terminal Essay" of his translation of the Arabian Nights, Richard Francis Burton notes that "the Afghans are commercial travellers on a large scale and each caravan is accompanied by a number of boys and lads almost in woman's attire with kohl'd eyes and rouged cheeks, long tresses and henna'd fingers and toes, riding luxuriously in Kajawas or camel-panniers: they are called Kuch-i safari, or travelling wives, and the husbands trudge patiently by their sides". Burton also reports a pederastic proverb common in the area: Women for breeding, boys for pleasure, but melons for sheer delight.[34]

Though no longer widely practiced, such boy marriages nevertheless still occur. However, in part as a result of resurgent Islamic fundamentalism, they are less well received than in former times. In late 2005, the Afghan refugee Liaquat Ali, 42, and his Pakistani beloved, Markeen Afridi, 16, were both threatened with death by the tribal elders, subsequent to their public and ceremonial wedding in the Tribal Territories (The Sydney Morning Herald).

In the aftermath of the US-Afghan war, western mainstream media have reported derisively on patterns of adult-adolescent male relationships, documented in Kandahar in Afghanistan (The New Yorker) and in Pakistan (The Boston Globe), often conflating them with pedophilia. The youth in these relationships, usually in his early-to mid-teens, is known alternatively as haliq, "beautiful boy", or ashna, "dear friend", and the man as mehboob, "lover", from the Persian mohabbat, "love", related to its Arabic counterpart, mahabbâh. The term balkay, referring to a beardless boy sexually available to men has also been reported.[35] The prevalence of homosexual relationships in Kandahar and other Pashtun areas has been explained in these articles as a behavior resulting from strict gender segregation (Los Angeles Times) and "without any moral or educational value".

These reports however have been characterized as "privileging a political spin over more precise and informative writing", and as suffering from ethnocentric bias (Stephanie Skier, in ''queer''). Brian James Baer, writing in the Gay and Lesbian Review (March–April, 2003), claimed that "their subtext was clearly aimed at discrediting the Pashtun tradition by equating it with the ultimate American taboo, adult sex with minors", and that "Western journalists insisted on reducing relationships that are often long-term emotional bonds to a crude sexual bargain". In contrast, alternative media have carried accounts by native sources describing married men engaging youths in mutually affectionate long term relationships[citation needed].

Besides relationships following the pederastic model, cases of sexual brutality by men against youths—in this instance as one aspect of the military use of children—have also been documented. In Afghanistan, out of the thousands of Pakistani boys recruited by mullahs under the guise of jihad to fight for the Taliban, it is thought that about 1500 survived, only to be held for ransom in private jails, where they were being systematically abused (Jeffrey Gettleman in the L. A. Times, July 2001). Also, commercial sexual exploitation of boys in Pakistan is reported to be widespread despite the fact that prostitution of minors is illegal and there is a death penalty for child abusers, according to the Bangkok-based international child protection campaign group ECPAT (End Child Prostitution, Child Pornography and Trafficking of Children for Sexual Purposes).

In the northern, Turkic-speaking areas, one manifestation of the pederastic tradition were the entertainers known as bacchá (a Turkic Uzbeki term etymologically related to the Persian bachcheh, "boy" or "child", sometimes with the connotation of "catamite"). A bacchá, typically an adolescent, was a performer practiced in erotic songs and suggestive dancing. He wore resplendent attire and makeup, and would also be available as a sex worker. These Muslim bachás were trained from childhood and carried on their trade until their beards began to grow. Though after the Russian conquest the tradition was suppressed by tsarist authorities, early Russian explorers were able to document the practice.

Sufi outlook

The manifestations of pederastic attraction vary. At one extreme they are indeed of a chaste nature, incorporated into Islamic mysticism (see Sufism) as a meditation known in Arabic as nazar ill'al-murd, "contemplation of the beardless", or shahed-bazi, "witness play" in Persian. This is seen as an act of worship intended to help one ascend to the absolute beauty that is God through the relative beauty that is a boy. Modern Sufi thought asserts that this contemplation uses imaginal yoga to transmute erotic desire into spiritual consciousness.

Richard Francis Burton, in his "Terminal Essay" (Part D) to the Arabian Nights, claims that Easterners value the love of boys above the love of women, using Persian terminology in which the moth and the bulbul (nightingale) represent the lover, and the taper and the rose represent the boy and the girl, respectively: "Devotion of the moth to the taper is purer and more fervent than the Bulbul's love for the Rose".

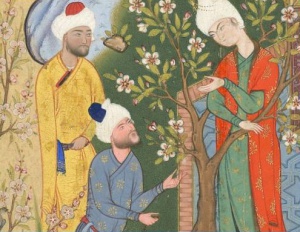

In an illuminated manuscript of Sufi poet Abdul-Rahman Jami's (1414–1492) Haft Awrang (see manuscript), an anthology of seven allegorical poems on wisdom and love, there is a calligraphed verse in the section titled "A Father Advises his Son About Love" (in which a father instructs his son, when choosing a worthy male lover, to chose that man who sees beyond the mere physical and expresses a love for his inner qualities). The verse exemplifies one Sufi way of turning love into wisdom:

I have written on the wall and door of every house

About the grief of my love for you.

That you might pass by one day

And read the state of my condition.

In my heart I had his face before me.

With this face before me, I saw what I had in my heart.

Nazar was a principal expression of a male love that, according to the teachings, was not to be consummated physically.

Not all followed the teachings to the letter. On being challenged by Rabi’a al-‘Adawiyya (c.717–801) of Basrah (Sufi woman saint who first set forth the doctrine of mystical love), upon noticing him kissing a boy, for appreciating the beauty of boys above that of God, the ascetic Sufi Rabah al-Qaysi retorted that, "On the contrary, this is a mercy that God Most High has put into the hearts of his slaves" (Abu 'Abdur-Rahman as-Sulami, pp. 78–79). Others also suspected the motives of dervishes who professed to love only the appearance of the boys, as reflected in this Egyptian proverb: In his father's home a boy's chastity is safe, but let him become a dervish and the buggers will queue up behind him.[36]

Conservative Muslim theologians condemned the custom of contemplating the beauty of young boys. Their suspicions may have been justified, as some dervishes boasted of enjoying far more than "glances", or even kisses. Nazar was denounced as rank heresy by such as Ibn Taymiyya (1263–1328), who complained, "They kiss a slave boy and claim to have seen God!". The real danger to conventional religion, as Peter Lamborn Wilson asserts, was not so much the mixing of sodomy with worship, but "the claim that human beings can realize themselves in love more perfectly than in religious practices". Despite opposition from the clerics, the practice has survived in Islamic countries until only recent years, according to Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe (see References section below).

Modern scholarship

The traditional tolerance, literary and religious, for chaste pederastic love affairs which was prevalent since the 8th century began to be eroded in the mid-1800s by colonization by the West, with the forcible imposition of Western values and laws (European visitors to pre-colonization Middle East unanimously report, with various degrees of excitement or outrage, how shockingly common boylove and other sexual practices were). Even in countries never colonized, such as modern-day Turkey, the adoption of European Victorian attitudes by the new westernized elite accomplished much the same thing.[citation needed] Historical material is reported to be systematically distorted.[citation needed] In his monograph on same-sex relations in the pre-modern Middle East, Khaled El-Rouayheb demonstrates how Persian and Arabic love poetry and other literary material is routinely heterosexualized or devalued in critical studies authored by post-colonial Arab and Islamic scholars.[37] Similarly, the works of Abu Nuwas, widely available in their entirety in the Arab world until modern times, were first published in expurgated form in Cairo in 1932.[38]

Under the rule of both the Pahlavi dynasty monarchy and the Islamic Republic in Iran, Janet Afary claims that "Classical Persian literature—like the poems of Attar (died 1220), Rumi (d. 1273), Sa’di (d. 1291), Hafez (d. 1389), Jami (d. 1492), and even those of the 20th century Iraj Mirza (d. 1926)—are replete with homoerotic allusions, as well as explicit references to beautiful young boys and to the practice of pederasty". She further states that "professors of literature have been forced to teach that these extraordinarily beautiful gay love poems aren't really gay at all and that their very explicit references to same-sex love are really all about men and women".[39][40]

Two Western scholars ignore such material. In a 1999 review in The Spectator of an anthology of Classical Arabic literature, the reviewer, R.I. Penguin, says of the author's editorial decision to focus on nature: "Irwin is to be admired for sticking to a fair-minded overview of the whole field; Sanawbari's work, for instance, is described thus: 'Besides nature poems, he also produced mudhakarat, or poems addressed to small boys. However, in this anthology we will stick to the nature poems.' Quite right; the nature poems are much more interesting". Irwin also notes that "... there are some practices in the poetic language which sound bizarre, like the convention that if the metre demands it, the masculine pronoun may be substituted for the feminine one, with deeply confusing results in love poetry. The Arabs were fairly polymorphously perverse, but probably not so much as their love poetry makes them sound".[41]

See also

Further reading

- Ofri Ilany, "How did homosexuality become so offensive to the Muslim world? It wasn't always this way", Ha-Aretz (The Land) [Tel Aviv], June 19, 2016.

Notes

- 'Abdur-Rahman as-Sulami, Abu. Early Sufi Women, Dhikr an-niswa al-muta'abbidat as-sufiyyat. Louisville, KY: Fons Vitae, 1999.

- Aldrich, Robert. Gay Life and Culture: A World History. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2006.

- Andrews, Walter G. and Mehmet Kalpakh. The Age of Beloveds. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2005.

- Crompton, Louis. Homosexuality and Civilization. Belknap, Harvard, 2003. (ISBN 0-674-01197-X)

- García Gomez, Emilio (ed. and translator from Arabic to Spanish), In Praise of Boys: Moorish Poems from Al-Andalus. Translated from the Spanish by Erskine Lane. Gay Sunshine Press, 1975.

- Gürgan, Burcu. "Images of sexuality in the 16th century Ottoman society", 2005.

- Kennedy, Philip F. The Wine Song in Classical Arabic Poetry: Abu Nuwas and the Literary Tradition. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997. (ISBN 0-19-826392-9)

- El-Rouayheb, Khaled. The Love of Boys in Arabic Poetry of the Early Ottoman Period, 1500–1800. Middle Eastern Literatures; January 2005, Vol. 8, No. 1.

- El-Rouayheb, Khaled. Before Homosexuality in the Arab-Islamic World, 1500–1800. Chicago, 2009. (ISBN 9780226729893)

- Kuru, Selim S. "A Sixteenth Century Scholar: Deli Birader and His Dafi ü'l-Gumûm Ve Rafi ü'l-Humûm" (2000). Unpublished PhD Dissertation. Harvard University.

- Tīfāshī, Aḥmad ibn Yūsuf; Khawam, René R., Lacey, E.A. (translator). The Delight of Hearts: Or, What You Will Not Find in Any Book. Gay Sunshine Press, 1988. (ISBN 0-940567-09-1).

- Murray, Stephen O. and Will Roscoe, et al. Islamic Homosexualities: Culture, History, and Literature. New York: New York University Press, 1997. (ISBN 0-8147-7468-7).

- Ritter, Hellmut. Das Meer der Seele, 1955 (English translation: The Ocean of the Soul, 2003). (Chapters 24, 25 ,26).

- Wilson, Peter Lambourn. Contemplation of the Unbearded: The Rubaiyyat of Awhadoddin Kermani. Paidika, Vol.3, No.4 (1995).

- Roth, Norman. "The Care and Feeding of Gazelles: Medieval Hebrew and Arabic Love Poetry". Poetics of Love in the Middle Ages, 1989.

- Roth, Norman. Fawn of My Delights: Boy-Love in Hebrew and Arabic Verse". Sex in the Middle Ages, 1991.

- Roth, Norman. "Boy-Love in Medieval Arabic Verse". Paidika, Vol. 3, No. 3, 1994.

- Schild, M. "The Irresistible Beauty of Boys: Middle Eastern Attitudes About Boy-Love". 1.

- Sikand, Yoginder. "A Martyr for Love: Hazrat Sayed Sarmad, a Sufi gay mystic". Perversions, Vol. 1, No. 4. Spring 1995.

- Williamson, Casey R. Williamson. Where did that boy go?: The missing boy-beloved in post-colonial Persian literature.

- Wright, J. W. & Everett Rowson. Homoeroticism in Classical Arabic Literature. 1998.

- Ze'evi, Dror. Producing Desire: Changing Sexual Discourse in the Ottoman Middle East, 1500-1900. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

References

- ↑ Walter Andrews and Mehmet Kalpakli, The Age of Beloveds: Love and the Beloved in Early–Modern Ottoman and European Culture and Society; Durham and London, 2005.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 The Rasa'il Ikhwan as-Safa', a tenth century Iraqi philosophical and religious encyclopedia.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 James T. Monroe, in Homoeroticism in Classical Arabic Literature, p. 117.

- ↑ Murray and Roscoe, 1997; passim.

- ↑ Mukhtar, M. H., Tarbiyat-e-Aulad aur Islam [The Upbringing of Children in Islam]. dar-ut-Tasneef, Jamiat ul-Ulūm il-Islamiyyah alla-ma Banuri Town Karachi. English translation by Rafiq Abdur Rahman. Transl. esp. Chapter 11: "Responsibility for Sexual Education".

- ↑ Khaled El-Rouayheb, Before Homosexuality in the Arab-Islamic World, 1500–1800; Chicago, 2005; p. 58.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories; I.135, tr. A.D. Godley.

- ↑ Plutarch, De Malig. Herod. xiii.II.

- ↑ Richard F. Burton, "Terminal Essay".

- ↑ From the Garden of Truth and Path to Enlightenment (tr. Paul Sprachman).

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20080301005048/http://www.breadnet.middlebury.edu/~nereview/Davis.html

- ↑ Minoo S. Southgate, "Men, Women and Boys: Love and Sex in the Works of Sa'adi", in Asian Homosexuality, ed. Wayne Dynes; p. 289.

- ↑ R. F. Burton, ibid.

- ↑ refer to The existence of male-male love subsection.

- ↑ refer to Sodomy and Islam subsection.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Khaled El-Rouayheb, Before Homosexuality in the Arabic World, 1500–1800, p. 3.

- ↑ A note provided by Selim suggested that gulampare and mahbub-perest are both boy lovers but the former implying sexual and the second platonic love. Selim S. Kuru (2000).

- ↑ Selim S. Kuru, "A Sixteenth Century Scholar: Deli Birader and His Dafi ü'l-Gumûm Ve Rafi ü'l-Humûm" (2000). Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Harvard University; pp. 184–185.

- ↑ Khaled El-Rouayheb, "The Love of Boys in Arabic Poetry of the Early Ottoman Period, 1500–1800"; Middle Eastern Literatures, January 2005, Vol. 8, No. 1.

- ↑ Selim S. Kuru. "A Sixteenth Century Scholar: Deli Birader and His Dafi ü'l-Gumûm Ve Rafi ü'l-Humûm" (2000). Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Harvard University; p. 189–191.

- ↑ Khaled El-Rouayheb, "The Love of Boys in Arabic Poetry of the Early Ottoman Period, 1500–1800"; Middle Eastern Literatures, January 2005, Vol. 8, No. 1, p. 5.

- ↑ ‘ārid in this context means bread down. Khaled El-Rouayheb, "The Love of Boys in Arabic Poetry of the Early Ottoman Period, 1500–1800", p. 4.

- ↑ Selim S. Kuru, "A Sixteenth Century Scholar: Deli Birader and His Dafi ü'l-Gumûm Ve Rafi ü'l-Humûm" (2000). Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Harvard University; pp. 188–92.

- ↑ (Toledano, 2003; p. 242). [Flaubert, January 1850:] "Be informed, furthermore, that all of the bath-boys are bardashes [male homosexuals]".

- ↑ (Gazali, 2001; p. 106.)

- ↑ Kemal Sılay, Nedim and the poetics of the Ottoman court (1994); Indiana University. ISBN 1878318098.

- ↑ Hobby-O, "Greece" (The Diary of John Cam Hobhouse, October 22nd 1809, edited by Peter Cochran).

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Khaled El-Rouayheb, Before Homosexuality in the Arabic World, 1500–1800, p. 42

- ↑ Khaled El-Rouayheb, Before Homosexuality in the Arabic World, 1500–1800, p. 41.

- ↑ Temeşvarlı Osman Ağa, Gâvurların Esiri; Istanbul, 1971.

- ↑ http://www.publicbookshelf.com/public_html/Our_Country_vol_2/usnavy_bgh.html

- ↑ http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/new-us-navy/navy-bill.html

- ↑ http://www.glbtq.com/literature/mid_e_lit_persian,2.html

- ↑ Sir Richard Burton, Kama Sutra: The Hindu Art of Lovemaking, intro. Pathan proverb, also reported in similar forms from the Arab countries, Iran and North Africa.

- ↑ M. Ismail, NGO Coalition on Child Rights–NWFP/UNICEF Community, "Perceptions of Male Child Sexual Abuse in North West Frontier Province, Pakistan"; NGO Coalition on Child Rights, 1998.

- ↑ Yusuf Al-Shirbini's 17th-century Kitab Hazz Al-Quhuf, as per Khaled El-Rouayheb, Before Homosexuality in the Arab-Islamic World, 1500–1800; Chicago, 2005; p. 37.

- ↑ [El-Rouayheb, 2005; p.156

- ↑ "Cultures of Denial", article in the book Unspeakable Love: Gay and Lesbian Life in the Middle East; in Al-Ahram, 4 May–10 May 2006, #793.

- ↑ http://gaycitynews.nyc/gcn_432/iraniansourcesquestion.html

- ↑ Janet Afary and Kevin Anderson, Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism; University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- ↑ Philip Hensher, "An orchard you can take on your lap", The Spectator, 27 November 1999.

External links

- The Androphile Project – The World History of Male Love

- Recognition vs. Acceptance: Islamic Discourses on Homosexuality

- Islam and Homosexuality – Ottoman Culture

- Homosexuality in Kitab-i-Aqdas

Real source: